Bb feb 2010 -

The population biology

of Common Sandpipers

in Britain

T. W. Dougall, P. K. Holland and D. W. Yalden

Abstract The population biology of Common Sandpipers

Actitis hypoleucos has

been studied, especially by colour-ringing breeding adults, at two sites, in the Peak

District and in the Scottish Borders. Adults are usually site-faithful, males more so

than females, contributing to a good apparent survival rate (72% and 67%,

respectively). Some, at least, return to breed at one year old, but usually not to the

site where they hatched. The population in Britain seems to be in slow decline,

most obviously indicated by a contraction along the edges of its range, which

results especially from poor recruitment of young birds. This does not seem to be

due to poorer breeding success, but it is uncertain whether it is caused by a subtle

effect of climate change, change in quality of stopover sites on migration, or

changes in wintering habitat. Since we don't know precisely where British birds

spend the winter, the last possibility is especially hard to evaluate.

or Wood Lark

Lullula arborea, but not suffi-

The Common Sandpiper

Actitis hypoleucos is

ciently abundant to benefit from mass

one of those ‘in between' birds – not rare

studies, like the Blue Tit

Cyanistes caeruleus

enough to have attracted devoted individual

or Robin

Erithacus rubecula. Unlike many

attention, like the Osprey

Pandion haliaetus

waders, it does not flock in large numbers to

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Common Sandpipers in Britain

fields, estuaries or the Bancd'Arguin, it is not censused bymoorland bird counts, andwhen on migration does not

get ringed in any great

numbers. There is a littleinformation from the Water-

ways Bird Survey on popula-

tion trends and the species

seems to have been targeted

by only one PhD study (Mee

2001). Our own, essentiallyspare-time, efforts have beenan attempt to fill in some of

the gaps. In reviewing whatwe have learnt, we inevitably

also highlight how much

remains unknown.

Study sites and

Fig. 1. Sketch map of the Ashop–Alport study site and the nearby

reservoirs in the Upper Derwent Valley, Peak District (areas of

Our efforts started with a

woodland shown in green, water features in blue; also shown is the

survey of numbers in the Peak

A57 between Manchester and Sheffield) (from Dougall

et al. 2005).

District in 1977–79, combinedwith a colour-ringing study ofbirds along a 10-km stretch of

the Rivers Ashop (‘Snake

Pass') and Alport (Holland

etal. 1982a,b). Of about 200pairs then breeding in the

Peak District, 20–22 pairs

occupied these valleys, withanother 45–50 pairs nearby on

the Ladybower-Derwent-

Howden (LDH) Reservoirchain. The Ashop flows intothe western arm of LadybowerReservoir, about 2 km down-

stream of the study site; thewhole forms part of theUpper Derwent catchment.

The colour-ringing study con-

tinues to the present day,giving 32 years of data (PKH,

then DWY), but has also beenextended to the reservoirchain. Thinking that a com-parative study would be

revealing, we started a parallel

investigation on the riversLeithen Water (8.5 km) and

Fig. 2. Sketch map of the Borders study site (woodland in green,

Heriot Water (6 km) in the

water features in blue; also shown is the B709 road fromEdinburgh to Innerleithen) (from Dougall

et al. 2005).

Moorfoot Hills, Borders, in

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Dougall et al.

1993 (TWD), and this also continues

returning migrants than the Peak District

(Dougall

et al. 2005; Pearce-Higgins

et al.

(hereafter referred to as Ashop) study area.

2009). This study site, and our knowledge of

On the other hand, the LDH reservoir chain

the species, benefited from an intensive PhD

has a shoreline of 30 km. This must also

study in 1998–99 (Mee 2001). The two

provide a good target for returning sand-

stretches of river are about 6 km apart, and

pipers, but is too extensive to be studied as

together perhaps provide a larger target for

intensively as the rivers. The whole shoreline

has been surveyedtwice (once in May,once in June) eachyear since 1992, andone or two ex-Ashopbirds are invariablypresent.

Adults are usually

caught on the riversin short, single-panelmist-nets set withinthe

usually targetingparticular individ-uals, and birds areringed with 3–4Darvic colour rings,as well as a BTO

metal ring, so that

individuals are sub-

29. An upper stretch of Glentress Water, near Blackhopebyres, in the

sequently recognis-

Borders study area. This shows the meandering river and the wide shingle

able in the field. In

banks that develop in the bends, producing favoured feeding sites for

Common Sandpipers

Actitis hypoleucos.

area, potential terri-tories are checkedweekly through Mayand June, sometimesinto mid July, for thepresence of colour-ringed birds. Nestsare rarely located,and the adults aresecretive

incubation, but oncethe chicks hatch,their parents becomevery vocal (‘alarm'),revealing roughlywhere their chicksare. By backing off,or using a car as a

hide, it is sometimes

possible to watch

30. A lower stretch of the Borders study site, on Glentress Water near

adults returning to

Whitehope. This is good habitat for Common Sandpipers

Actitis hypoleucos,

brood young chicks.

with wide shingle beds, cover for chicks in the boulders, and with theadvantage of the nearby road, allowing a car to be used as a hide; May 2009.

Every effort is made

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Common Sandpipers in Britain

to ring these, with a single(‘scheme') colour ring anda BTO metal ring. Ashopbirds receive a white ringon the right tibia as thescheme mark, while thosearound the reservoirs get alight blue ring on the lefttibia. The hope was thatrecruits to the Ashop fromthe reservoirs would bequickly recognised. In theBorders, chicks as well asadults were formerly fittedwith individually recognis-

able combinations, but in

more recent years both

31. ‘Walk-in' traps set at the waterline of Ladybower Reservoir,

chicks and adults have

May 2009. Two traps are set, facing in opposite directions, and with

scheme colours applied to

boulders or other debris to mask the outline of the trap, and

the right leg only: red on

mealworms on the bait trays as an added attraction.

tibia, orange over BTO on tarsus for adults;

quickly (and noisily) pair up, usually in their

orange on tibia, red over BTO on tarsus for

old territories, and have eggs by mid May. It

chicks. So far, neither Peak District nor Moor-

seems as though they fly into their territories

foot Hills birds have been seen in the recip-

very quickly (rather than trickle slowly up

rocal study area, but a juvenile ringed on

through the country, although there are some

autumn passage in Lancashire on 4th August

sightings in south and southwest England,

2001 (by PKH) was retrapped as a breeding

and in Wales, of colour-ringed Borders

bird south of Peebles, just outside the Moor-

birds). This impression is heightened by the

foots study area, on 29th May 2003. The age

fact that they get back to their territories in

of the chicks (and hence their hatch date) can

the Borders about a week earlier than those

be estimated from their bill length, and

in the Peak District. Young birds arrive back

weight relative to age gives an estimate of

5–10 days later, on average, than the old

condition (Holland & Yalden 1991b). Sexing

hands. Territories are usually 150–200 m long

Common Sandpipers is not easy, though

when there are neighbours to constrain

females are generally slightly larger (means

them, and are generally along stretches of

54 g v. 49 g; Mee 2001). The greater weights of

shingle shore with some cover for the chicks

females during egg-laying are revealing (they

(e.g. undercut shores, boulders, taller vegeta-

can weigh up to 82 g), and with colour-ringed

tion). Females typically lay a clutch of four

birds courtship behaviour can be helpful in

eggs (mean 3.65) in a nest on a grassy bank a

determining the sex of individuals. However,

few metres back from the water, but some-

both adults incubate, brood chicks and

times on shingle islands or at the top of stony

defend their territory against neighbours

reservoir shores; occasionally the nest may be

(sometimes making the mistake of chal-

over 100 m from the waterside. Incubation is

lenging their own returning mates!).

shared, but males sit mainly overnight and

Although the male usually follows behind the

females during daylight hours (Mee 2001).

female while she is feeding up prior to egg-

The eggs hatch from mid May (Borders)

laying, and signals to her with ‘wings-up', dis-

or the last few days of May into early June,

playing the strongly patterned underwing, the

but new recruits are later and pairs will

same display is used as a threat by both sexes.

produce a replacement clutch if the first islost, stretching the hatch dates to as late as

7th July. At hatching, chicks weigh around

Older Common Sandpipers reappear on

9.5 g and have a bill length of about 10 mm.

their breeding grounds in mid to late April,

Chicks are encouraged from the nest by their

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Dougall et al.

.Yalden. W

32. A typical Common Sandpiper

Actitis

hypoleucos nest, with a clutch of four eggs; this

33. A late, replacement nest, in growing

one, in a patch of Bracken

Pteridium aquilinum in

Bracken

Pteridium aquilinum, Ashop Valley,

the Ashop study area, 15th May 1984, belonged

9th June 1982; another of Red-Red's successful

to the long-lived male ‘Red-Red'.

parents, and for their first few days usually

this age to fledging: their camouflage, ability

frequent damp areas – rushes, streams trick-

to run and hide, and to dive and swim if sur-

ling over reservoir shores – where small

prised near deeper water, gives them an

insects are readily available. Mortality at this

ability to dodge most predators (and

stage is high, around 25% (Yalden & Dougall

ringers!). Detailed observations suggest that

2004), despite both parents being present as

they are thermally independent by then,

guards. Young chicks need brooding every

though older chicks may still be brooded in

seven minutes or so, and for about seven

rain and at night. From about seven days old,

minutes each bout. By seven days, the chicks

the chicks may be closely attended by only

are mobile, weigh around 16 g and have a bill

one parent, the other going off to feed nearby

length of 14 mm; most (75%) survive from

(though still alert to intruders). By their third

week (the chicks usuallyfledge in 19 days), oftenonly one parent is leftguarding the chicks, andusually stays beyondfledging for another weekor so. When one parentleaves early, it is usually,but not always, the female.

Partial desertion is morelikely with later-hatchingbroods (Mee 2001).

Clearly, their territory

is ver y important toCommon Sandpipers;both adults defend itagainst their neighbours.

Moreover, it is demon-

strably the stretch of

shoreline that they are

34. A brood of three young Common Sandpiper

Actitis hypoleucos

defending: the four neigh-

chicks, about four days old and about 20 m away from their knownnest-site; June 2009, Ladybower Reservoir.

bours will feed together

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Common Sandpipers in Britain

comfortably in nearbypasture, but renew ter-ritorial aggressionwhen they return tothe river. An analysisof habitat suggeststhat they need an areaof shingle, and theadults spend muchtime patrolling thewater's edge in searchof food. However,their diet contains aneven mix of aquaticprey (caddisfly (Tri-choptera),

(Ephemer optera) andstonefly (Plecoptera)larvae) and terrestrial

prey (click beetles

35. A young Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos chick, probably only a

(Elateridae), carabids

day or two old, still with a short (10 mm) bill; Whiteholme Reservoir,Yorkshire, June 2008.

earth worms (Lumbricidae)) (Yalden 1986),

and low recruitment. The Ashop had 20–22

so reliance on the water's edge to provide a

pairs in 1977–80. However, the severe late

food supply is not the whole story. The most

April (24th–26th) snowfall of 1981 apparently

prolonged territorial fight we have observed

surprised, and killed, a number of returning

(27 minutes) involved two pairs guarding

adults; the population dropped to 14 pairs

chicks, on 18th June 1989. One pair, dis-

that year, and recovered only slowly (by one

turbed by an angler, led its chicks into the

or two pairs a year) up to 1988 (Holland &

neighbouring territory, and to start with all

Yalden 1995). Another cold, late spring in

four birds were fighting (three of them were

1989 then caused another sharp decline, from

colour-ringed) (Yalden 1992a). One male

which the population has never properly

then led his chicks back, while his mate con-

recovered. Although there were 15 pairs in

tinued fighting for another 11 minutes. Such

2006, only five pairs were present in 2007 and

observations suggest that the most important

2008. Averaged over 28 years, the population

roles of the territory are toprovide the chicks with a

feeding area and good cover.

Territorial fights are certainlymore prolonged when chicks

are also present than early inthe season, when the briefest of

challenges is usually sufficient

to maintain territorial integrity.

The early years of study in thePeak District, and the early

years of the Waterways Bird

Survey (WBS), suggested a

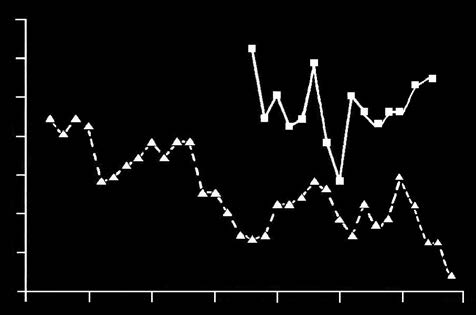

Fig. 3. The long-term decline of the Ashop–Alport Common

stable population, as might be

Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos population from 1977 to 2009, and

expected for a relatively long-

the fluctuating population in the Borders study site from 1993

lived species with high survival

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Dougall et al.

has declined by 59%. This matches what has

Survival rates, breeding success

happened more generally on the streams

around the Peak District, and the national

We have tried hard to understand the basis of

trend revealed by WBS and BBS (Breeding

the national decline, and the contrast in for-

Bird Survey), which suggests a 25% decline

tunes between the Peak District and Borders

over eight years (www.bto.org/birdtrends/

populations. Originally (1970s and 1980s)

wcrcomsa.htm). Over the shorter run of data

there was a strong correlation between sur-

from the Borders, there seems to have been

vival rates and minimum temperatures in

no decline, though much variability. Even

late April: fewer adults returned in cold

more puzzling, the LDH reservoir population

springs. Simple apparent survival rates

near the Ashop also shows no such decline.

(resighting of the previous year's colour-

There were 49 (±8) pairs in the early 1980s

ringed adults, on average 72% for males and

and 51 (±11) pairs in the 1990s and 2000s;

67% for females) declined between 80% and

indeed the highest count ever was as recent as

47% as late April mean minimum tempera-

2007, when 84 pairs were logged. In the

ture went down from 5.6 to 1°C (Holland &

Moorfoots, along a discontinuous 10.13 km,

Yalden 2002a). The variation in population

monitored annually between 1993 and 2007,

this produced matched changes in the North

the number of territories ranged between 14

Atlantic Oscillation (NAO); warm wet

in 2000 and 31 in 1993, and the percentage

winters (high NAO, perhaps snowier) are bad

which hatched at least one chick ranged

for sandpipers (Forchammer et al. 1998).

between 48% (in 2004) and 82% (in 2003)

However, in the 1990s, this relationship no

(Dougall et al. 1999; Dougall unpubl.).

longer fitted, though survival rates were still

While estimating the national population

just as variable, as were April temperatures

is fraught with difficulties (see below), it is

(Dougall et al. 2004). Not only did the

easier to map the breeding distribution.

Borders population not show the long-term

Between the two breeding atlases (1968–72

decline, but the considerable variations in

(Sharrock 1976) and 1988–91 (Gibbons et al.

populations there from year to year were not

1993)), the breeding range contracted, partic-

correlated with those in the Ashop popula-

ularly along the fringes of the species' range.

tion (Pearce-Higgins et al. 2009). If anything,

An apparent net loss of 14% of its breeding

survival rates were slightly higher in the

range in Great Britain and a substantial,

declining Ashop population than in the

though perhaps overestimated, 54% of its

Borders population, although the difference

Irish range suggests a considerable decline

was not significant.

(Yalden 1993). It will be fascinating to see

Breeding success is hard to evaluate pre-

what the third atlas reveals.

cisely; because well-grown chicks are so good

at running and hiding from any

threat, whether ringer or pred-ator, counts of older young or

fledglings are invariably underes-

timates. One calculation suggeststhat perhaps 35% of the actual

fledglings were not recorded(Yalden & Dougall 2004), another

that 30% were missed (Holland &

Yalden 1994). However, the fact

that their guarding parents are so

vocal suggests that at least the

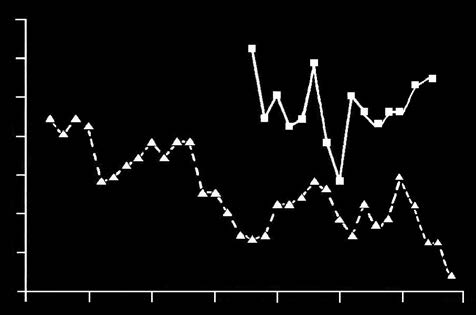

Fig. 4. This figure shows the slight negative correlation of

success of breeding attempts can

annual adult survival for the Ashop birds with winter North

be reliably counted: a territory

Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) values (yellow circles denote first-

that has ‘alarming' parents over

year birds, i.e. new recruits, red circles represent older

three or four weeks has surely got

adults) (from Pearce-Higgins et al. 2009). A higher NAO valueindicates a warmer, wetter winter in western Europe, but

at least one chick through to

cooler, drier conditions in NW Africa.

fledging. On that basis, there is no

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Common Sandpipers in Britain

evidence that breeding success has been

mate at least once (Holland & Yalden 1994).

poorer in the Ashop study area than in the

The converse pleasure is of discovering

Borders study area over the decade or more

that individual birds which have failed to

that both have been studied. What is clear,

return to their territories have moved else-

however, is that recruitment of ‘new' birds, as

where (emigrated) rather than died. Obvi-

well as returns of fledglings, is very much

ously, this does not happen often. One 1980

higher in the Borders than in the Peak Dis-

female that had been presumed dead in the

trict. Only one of the 99 chicks and fledglings

1981 spring was found in 1982, about 20 km

ringed in the Ashop study area over the 1990s

away to the southwest in the Goyt Valley,

returned to breed there, but 49 of 421 ringed

where she returned in 1983 and 1984. In

in the Borders did so. Over the same period,

1990–93, ten birds from the supposedly site-

while 68 adults were recruited to the Ashop

faithful Ashop population contributed

population, there were 172 new adults ringed

further to the decline there by moving to

in the Borders (Dougall et al. 2005). The

LDH. One, having bred successfully along the

attempt to identify the source of new recruits

Ashop in 1992, as a new recruit, returned

to the Ashop population did find four birds

there briefly in April 1993, but in June 1993

bearing LDH light blue rings, including what

was at Derwent Reservoir, guarding a family,

has become the record for longevity. A 13-

as he was in 1994, 1995, 1996 and 1997. This

day-old chick ringed as NV54164 at Lady-

example highlights one of the mysteries of

bower Reservoir on 21st June 1992 turned up

this species. What are returning birds,

as a breeding male 7 km away in one of the

whether old hands or new recruits, looking

upper territories on the Ashop in May 1993,

for when they get back? If they were heading

with an unringed female. Both were caught

for familiar habitat, we might expect riverine

and individually colour-ringed, but their

birds to return to rivers and reservoir birds to

breeding attempt failed that year, and the

return to similar shorelines. Obviously, estab-

female was never seen again. The male didn't

lished birds return to their familiar territory,

return to the Ashop, but in May 1994 was

and get back to claim it as quickly as possible.

seen three times with an unringed female at

Often, they also meet their old mate there,

Ladybower, about 3 km south of where he

and experienced birds are more likely to

hatched. He was seen back in that territory

breed successfully together (Mee 2001).

every year to 2007, being last recorded on

Rarely, females get back before their mate,

19th June 2007; moreover, judging by his

and may then pair with an already estab-

‘alarming' behaviour in June, he bred suc-

lished (but different) male. Are birds that

cessfully in 11 of his 14 years at Ladybower,

move sites ones whose mate fails to return?

and at 15 years old was much the oldest

Are they looking to set up territories near

Common Sandpiper that we or anyone else

other, already established, birds or pairs, on

has recorded.

the basis that their presence signifies a suit-

This sort of resighting is one of the

able site? If the latter is true, it might explain

delights of studying this species. The birds

the geographical retreat from peripheral

are highly site-faithful (and if they were not,

parts of the range, in the Peak District cer-

the apparent survival rates would be much

tainly, but also in northeast Scotland and in

poorer). An early calculation was that 89% of

Ireland, as revealed by Gibbons et al. (1993).

returning males and 78% of returning

It is possible that some of the apparent con-

females came back to the same or an adjacent

traction in range was actually a consequence

territory (Holland & Yalden 2002a). So, in

of less thorough surveying of the thinly pop-

late April, checking the rivers to see who is

ulated periphery of the species' range in

safely back, and with whom they are paired,

1988–91, especially in Ireland, although local

is a special pleasure. With an average survival

accounts confirm losses in many areas.

rate of about 80%, adult life is likely to lastthree years, so the chances of both members

of a pair returning are only about 50%. Put

Given that chicks wear at least a scheme ring,

another way, a bird that holds territory for

any that return to our study areas are con-

three years is statistically ‘bound' to get a new

spicuous, and targeted (albeit not always suc-

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Dougall et al.

perhaps a large proportion, ofthem. This is an aspect of ourstudies where sightings fromothers would be especially valu-able.

Migration and wintering

This section deals with our biggest

uncertainties! There are ringing

recoveries of British birds moving

south in Britain, and from France,

Spain, Portugal and Morocco, in

July–October. Similarly, there are

recoveries of returning birds,

through Morocco, Spain and

France in March–April. These

include recoveries/resightings of

36. A well-grown Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos chick,

our own birds in southern

within about two days of fledging (bill length 19.7 mm, wing

England, France, Iberia and

length 79 mm, but underweight at 27.5 g), showing remnants

Morocco. None of our birds has

of chick down on the nape and tail. The red ring above the

been seen in November–February,

BTO metal ring identifies this as a chick from the Borders

and, more surprisingly, there has

study site; Leithen Water, June 2005.

been just one recovery from West

cessfully) for recapture, identification and

Africa of the 19,000+ Common Sandpipers

full colour-ringing. This gives us a measure

ringed in Britain. This was of a bird ringed at

of natal dispersal – the distance between

Abberton Reservoir, Essex, in July 1964 and

hatching and establishment of a breeding ter-

recovered in Guinea-Bissau in September

ritory in later years – but this is clearly going

(though birds ringed at Abberton are mostly

to be an underestimate, since we are more

Scandinavian birds on passage, as nine other

likely to detect a ringed new recruit within

recoveries in Scandinavia testify). The nearest

our study areas than farther afield. Of 36

thing to a recover y in West Africa of a

Borders chicks that returned later to breed,

British-bred bird involves an unfortunate

they were between 0 and 39 km from where

chick ringed at Grassington, Yorkshire, on

they hatched, and at a median distance of 6

2nd June 1963. Its remains were recovered on

km. It is probably no coincidence that this is

20th November 1963 from the radiator of an

roughly the distance between the two parts,

aircraft that landed at Moscow airport after a

Heriot Water and Leithen Water, of the study

journey from Accra (Ghana) via Conakry

site. In the Peak District, the 35 returning

(Guinea), Bamako (Mali) and Belgrade. The

chicks were between 0.7 and 138 km away,

likelihood is that this young bird had been

with a median of 3.3 km, which is, similarly,

caught up in Guinea or Mali; this is roughly

roughly the distance between the Ashop and

where we would predict British birds to be in

the LDH reservoirs (Dougall et al. 2005).

winter on the basis of the SSW trend shown

How biased are these two figures? We have

by recoveries of Common Sandpipers ringed

had a few exchanges between the Goyt Valley,

elsewhere in Europe (Poland, Germany,

20 km to the southwest, and the Upper

Russia) and recovered in West Africa

Derwent, and there is a weak correlation,

(Holland & Yalden 2002b).

with a two-year lag, between population

Common Sandpipers move south in

changes in the Ashop population and those

summer very quickly. Our study sites are

in the Goyt. The most distant return, at 138

usually already thinly populated by early July,

km, was in north Wales. If our returns are

and typically empty before the end of the

spread so far, it is obvious that a search con-

month. Some have been recovered in Por-

centrated within 10 km or so of the sites of

tugal and Spain as early as mid July, and we

ringing is going to miss a proportion,

suspect that failed breeders may leave for

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Common Sandpipers in Britain

Africa very quickly. One Peak District bird

at St Abbs Head, Borders (Dougall & Yalden

was recovered, already back in Morocco, on

2007). These August falls are presumably of

15th June 1979. On the other hand, we also

Scandinavian birds on passage, but the July

have recoveries (and sightings of colour-

flocks are likely to be from more local

ringed birds) into August of sandpipers still

breeding areas.

in Britain, and we suspect that juveniles are

A small minority of Common Sandpipers

in less of a hurry to reach Africa.

remain in Britain overwinter. We know little

Over a period of 12 years, PKH succeeded

about these, either. On the basis that, in birds

in fitting colour rings to 60 full-grown birds

generally, those summering farthest north

near the mouth of the River Lune. It was

winter farthest south, whereas those in the

thought that these might be a sample of the

middle of the range move relatively little, we

100 pairs or their offspring that breed higher

would expect that Scandinavian birds overfly

up the Lune catchment. Yet none of these was

Britain. Birds wintering in Britain are more

ever seen on territory there in later years, nor

likely to be part of our summering popula-

were any of 38 birds ringed on those

tion. The chances of spotting one of our

breeding areas ever seen at the mouth.

colour-ringed breeding birds still in Britain

However, one was seen later breeding in the

in winter seem slight, but would be a worth-

Borders (see above) and another in

while target for those with telescopes or

Northumberland. Evidently, the mouth of

digiscoping equipment. If some of the

the Lune is a feeding-up site for birds from

Common Sandpipers overwintering in

the Borders. The mean weight of these birds

Britain could be caught and colour-ringed,

was 66 g, but the six heaviest weighed 80, 80,

they are perhaps more likely to yield a

81, 81, 82 and 84 g. Others have also reported

resighting in summer. Birds regularly

birds fattening up to over 80 g at sites away

hunting along reservoir shores can some-

from their breeding grounds (e.g. Brown

times be caught in walk-in traps or small

spring-traps (Dougall & Yalden 2008). Trap-

Relatively large concentrations of

ping may also confirm that wintering birds

migrating birds sometimes occur in autumn,

are site-faithful to their wintering territories,

for example 100 at Carron Valley Reservoir,

as suggested by one caught on Southampton

Upper Forth, on 7th July 1984; 64 at Endrick

Water on 6th January 1974 that was caught

Mouth, Clyde, on 25th July 1977 and 14th

there again on 18th March 1975. The ringing

August 1978; and 83 roosting at the River

expeditions to Djoudj, Senegal, in the early

Dumfries & Gal-loway, on 25th July2003. Occasionallythere are ‘falls' inthe Northern Islesand along the eastcoast of Scotland,most

during 18th–22ndAugust 2001, whenthere were 15 onFair Isle; seven onNorth Ronaldsay;50 on the Isle ofMay; 23, 11, nine

and eight at foursites in the East

Fife; 37. An adult (female?) Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos executing a

seven at Skateraw,

‘double wing-up', showing the striking underwing pattern. This is both a

Lothian; and eight

threat and a courtship display. Whiteholme Reservoir, Yorkshire, April 2007.

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Dougall et al.

1990s showed that Common Sandpipers

(51%) were recorded (Dougall et al. 2005).

ringed there had a higher return rate (9/65 or

However, given the median natal dispersal

14% after one year) than any of the other

distance of 6 km, and a range up to 39 km, it

waders, implying that they were indeed site-

is not known if the ‘missing' 49% were in fact

faithful (Sauvage et al. 1998). Limited obser-

recruited elsewhere, or if mortality rates are

vations suggested that they established

higher than we assumed. Moreover, we must

territories of about 200 m in length along the

expect that first-year survival rates vary

banks of the Senegal River, and defended

widely, as they do for adults, with weather

them against neighbours, but there is scope

and other conditions, but we know nothing

for considerable work on the species' winter

of this. Colour-ringing studies of wintering

birds, comparing adult and first-year survival

We have estimated that around 54% of

rates, would be interesting. Although they

newly hatched chicks survive to fledging

reach adult size by the time they fledge,

(Yalden & Dougall 2004), and we have a good

juvenile sandpipers have more conspicuous

set of estimates for adult survival (more

barring on their primary coverts, so they

strictly, adult return rates) from resighting

would still be recognisable as young birds

our colour-ringed birds (see above). Because

when they reach Africa.

fledglings rarely return to their natal sites, at

Returning birds, as we remarked above,

least in the Peak District, we have no clear

seem to return quickly to their territories.

estimate of the survival rate of first-year birds

However, this is clearly a stressful time. In

over their first winter. When the Ashop pop-

addition to the suspected, and recorded,

ulation was stable, we could create a balanced

mortality in 1981, recoveries in other years

life table by assuming that 57% of young

are quite frequent in late April/early May. A

birds survived their first winter. Using that

conspicuous example is NV82841, ringed as a

assumed survival rate, we might have

chick on 8th June 1996 at Garvald Lodge,

expected 96 recruits to the Borders popula-

Heriot Water. He was not seen again until

tion from the 1993–2002 cohorts; and 49

2002, when he was breeding successfully, at

David Hutton

38 & 39. Two splendid portraits of Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos ‘Light blue//BTO,

orange/black, photographed on migration at Seaswood Pool, Nuneaton, Warwickshire, on 15th April

2008. It had been ringed as a newly fledged juvenile at Ladybower Reservoir on 10th July 2002.

It was seen in its territory at the northeastern end of Derwent Reservoir in June 2004, June 2005,

May 2007 and June 2008, and was retrapped there on 28th May 2009.

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Common Sandpipers in Britain

Whitehope, 6 km to the south, and he was

rivers. A major problem, of course, is to

there again in 2003 and bred successfully

translate observed linear densities (per km of

with the same mate. On 22nd April 2004,

river or shoreline) into sensible figures for

though, he was found dead at Devizes, Wilt-

areas. Among a variety of estimates, we sug-

shire. His mate returned safely, took a new

gested that 1.6 pairs per monad (1-km

mate, was unsuccessful in breeding and was

square) was the most plausible (Dougall et

never seen again.

al. 2004), while the BBS suggested that 2% ofthe monads in England and Wales but 15%

Estimating the size of the British

of those in Scotland were occupied; there are

few data for Ireland, but we assumed that

Given our interest in the densities of birds in

5% of monads were occupied. The total

our study areas, it was a natural progression

occupancy for Britain & Ireland is then

to attempt to estimate the size of the total

19,500 monads, with a breeding population

breeding population of Britain & Ireland.

of 30,622 pairs, twice the number estimated

In the New Atlas (Gibbons et al. 1993), it was

in Gibbons et al. (1993). Moreover, a recal-

suggested that the population of a hectad

culation of the appropriate figure for the

(10-km square) might be 15 pairs, implying

1968–72 breeding atlas (Sharrock 1976) sug-

a population of 15,000 pairs in Great Britain

gests a population then of 39,600, and thus a

and 2,500 pairs in Ireland. This figure was in

decline of 23% between the two breeding

part suggested by our earlier estimate of the

atlases. A decline of 23% is also suggested by

Peak District population (11 pairs per hectad

the WBS, albeit between 1989 and 1999

averaged over 18 hectads), tempered by

(Dougall et al. 2004). Using the same

some acknowledgment of the fact that the

methodology, we estimated the nationally

species was clearly most abundant in Scot-

important Scottish population to be in the

land. Since the 1980s, many more surveys

range of 17,000–24,000 pairs, most probably

have been published, including both local

around 19,000 pairs (Dougall & Yalden

tetrad atlases and particular surveys of

David Hutton

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Dougall et al.

Causes of the decline

tering birds) and near our two study sites in

Our attempts to explain the decline of the

Britain, produced evidence of some effect of

national and Ashop populations by studying

climatic variation (NAO) on adult survival

the population dynamics of the Ashop birds

rates, and declining adult survival rates

and contrasting these with patterns in the

explained the overall population decline;

Borders have not been especially fruitful.

however, there was no evidence that any

Adult survival rates and breeding success

long-term trend in climate was responsible

seem comparable between the two areas

for the decline of the Ashop population

(Dougall et al. 2005). There is clearly a major

(Pearce-Higgins et al. 2009). Increased agri-

discrepancy in recruitment rates between the

cultural use of the wintering grounds or the

two areas, but we are not clear what underlies

stopover sites on migration might be

this. Possibilities include the poorer survival

affecting return rates. In Britain, it is evident

of first-winter birds in West Africa and

that the decline is most marked on smaller

poorer survival on migration. If there is

streams and rivers. Moreover, this retreat

poorer survival of young birds, is this a con-

from small streams has been proceeding for a

sequence of climatic changes? Alternatively,

century or more (Holloway 1996). Are these

are new recruits put off by finding poorer

sites more affected by agricultural change

breeding habitat on the rivers when they get

than larger sites? The species is certainly sus-

back so that, perhaps, they take territories on

ceptible to recreational disturbance, from

reservoirs instead? These ideas merit some

both anglers and picnickers (Yalden 1992a),

and this is regularly cited as a harmful factor.

A recent attempt to correlate changes in

The pair described earlier that led their

population size from year to year with

chicks into their neighbours' territor y,

climatic variation, both in Africa (for win-

inducing a prolonged fight, did so because an

angler was standing in the middleof their own territory. Conversely,the species responds quickly to theprovision of secure sites (islands,fenced areas). However, in the PeakDistrict, reservoir shores suffermore human intrusion than thestreams, so the cause-effect correla-tion is weak.

One interesting possibility is

that climate change might beaffecting the populations of somefreshwater prey. Many of thecommon stream larvae prefercolder water (Durance & Ormerod2007). Stream temperatures wouldbe much more sensitive to fluctu-ating weather than reservoirwaters, which are buffered by theirlarge volume. Stream invertebratesare also more exposed to changesin management regimes on neigh-bouring farmland. A regular

hazard of mist-netting at dusk usedto be getting dor-beetles Geotrupescaught in the nets; it was quite

usual to get three or four in an

40. An adult Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos carrying

just a BTO metal ring – against the grey legs, these are easily

evening whereas now there are not

missed; Whiteholme Reservoir, Yorkshire, June 2008.

that many in a season. Are the cow-

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Common Sandpipers in Britain

pats now inhospitable to beetle larvae

sandpipers do migrate in long hops, it might

because of the use of ivermectin vermifuges

explain why relatively few are seen in July in

on cattle? Many smaller invertebrates also

southern England as they migrate south

emerge from dung, and are eaten by sand-

(although more are seen in August, these are

pipers. Reduced sheep numbers mean that

probably Scandinavian birds). There are

vegetation is now longer along some stretches

major uncertainties with this scenario. Some

of Heriot Water; chicks are harder to locate,

evidence from elsewhere in Europe suggests

but they might also be less able to feed freely.

that Common Sandpipers accumulate little

In places, the shingle is becoming overgrown,

or no weight at stopovers (e.g. Meissner

so that too is less suitable feeding habitat.

1997, Arcas 2001). Is this a strategy that

An entirely different scenario is suggested

varies among populations, or age groups?

for the wintering habitat by recent surveywork in West Africa. In some places at least,

wintering Common Sandpipers frequent

We have learnt much about our favourite

mangrove swamps and roost communally,

bird in over 30 years of study. What began as

though it is not certain whether they also

a very local concern (how many Common

defend territories while feeding. Trolliet &

Sandpipers are there in the Peak District and

Fouquet (2004) suggested that 15,000 feed in

how is the population balanced?) has

mangrove areas and another 8,000 on the

expanded to a second study (do Borders

mudflats of Guinea; this could be a substan-

birds vary the same way?), and to national

tial proportion of the British population, if

concerns (how many breed, how is the popu-

Guinea is where they winter. Mangroves are

lation changing?). Now we are faced with

highly productive, but also subject to intense

problems on a flyway scale. We suspect that it

pressure from coastal development, for fish

is this wider population that is declining, not

farming, timber, and agriculture. Apparently,

just the Ashop or British ones (Sanderson et

Common Sandpipers exploit the abundance

al. (2006) suggested a 49% decline across the

of fiddler crabs Uca in this habitat. Therefore,

Western Palearctic). Greater understanding

this habitat is highly susceptible to human

of the species will require a co-ordinated

intervention and could be that in which most

international effort. We urgently need to

of our birds overwinter. However, it is

locate the wintering areas and habitats of the

unlikely to be affected by winter rainfall or

bulk of our birds. If there are routine

temperature, as would be expected if the

stopover points during migration, these too

Sahel region (as at Djoudj) is their main win-

need to be established. The attachment of

tering area. Thus our failure to detect any

satellite or radio tags would be one, albeit

obvious relationship between year-on-year

expensive, way to do this (cf. the studies of

population change and weather variation in

White-rumped Sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis;

West Africa (Pearce-Higgins et al. 2009)

Harrington 1999). An alternative would

might fit with such a wintering habitat.

involve routine studies on the wintering

Migration remains an area of major

areas, similar to ours on the breeding sites.

uncertainty and concern. Fat-free mass seems

Given the numbers of ringers and other

to be about 40 g (Baccetti et al. 1992). If our

ornithologists visiting exotic locations, as

birds regularly accumulate 40 g of fat (as

well as dedicated expeditions and collabora-

implied by birds weighing over 80 g in July),

tive studies with local birdwatchers in West

and have an average wingspan of 350 mm, we

Africa, we hope that someone will take up

can calculate that they should have a flight

this challenge.

range of 6,000 km in still air (Pennycuick1989). This would easily take them to the

Senegal River mouth in one hop, farther if

We must thank the estates and farms on whose land

they exploit tailwinds. If this is optimistic,

we have worked for their permission to do so, and

two major refuelling stops in, say, Morocco

those who have helped with our fieldwork (as detailed

and Senegal would enable an easier migra-

in, for example, Dougall et al. 2005). We also thank thephotographers for the accompanying images. Sightings

tion; if such sites exist, they need to be identi-

of colour-ringed birds away from our study sites can

fied so that they can be protected. If

be reported to [email protected]

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Dougall et al.

— & — 2002b. Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos.

Arcas, J. 2001. Body weight variation and fat deposition

In: Wernham, C. V., Toms, M. P., Marchant, J. H., Clark,

in Common Sandpipers during their autumn

J. A, Siriwardena, G. M., & Baillie, S. R. (eds.),

migration in the Ria de Vigo, Galicia, north-west

The Migration Atlas. movements of the birds of Britain

Spain. Ringing & Migration 20: 216–220.

and Ireland. Poyser, London.

Baccetti, N., de Faveri, A., & Serra, L. 1992. Spring

—, Robson, J. E., & Yalden, D. W. 1982a. The status and

migration and body condition of Common

distribution of the Common Sandpiper (Actitis

Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos on a small

hypoleucos) in the Peak District. Naturalist 107:

Mediterranean island. Ringing & Migration 13: 90–94.

Brown, S. C. 1974. Common Sandpiper biometrics.

—, — & — 1982b. The breeding biology of the

Wader Study Group Bull. 11: 18–22.

Common Sandpiper (Actitis hypoleucos) in the Peak

Dougall, T. W., & Yalden, D. W. 2007. Common

District. Bird Study 29: 99–110.

Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos. In: Forrester, R. W.,

Holloway, S. 1996. The Historical Atlas of Breeding Birds

Andrews, I. J., McInerny, C. J., Murray, R. D.,

in Britain and Ireland: 1875–1900. Poyser, London.

McGowan, R. Y., Zonfrillo, B., Betts, M. W., Jardine,

Mee, A. 2001. Reproductive strategies in the Common

D. C., & Grundy, D. S. (eds.), The Birds of Scotland,

Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos. Unpubl. PhD thesis,

pp. 679–681. SOC, Aberlady.

University of Sheffield.

— & — 2008. Catching Common Sandpipers.

Meissner, W. 1997. Autumn migration and biometrics of

Ringers' Bull. 12(4): 56–57.

the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos caught in

—, Holland, P. K., & Yalden, D. W. 2004. A revised

the Gulf of Gdansk. Ornis Fennica 74: 131–139.

estimate of the breeding population of Common

Pearce-Higgins, J. W., Yalden, D. W., Dougall, T. W., &

Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos in Great Britain and

Beale, C. 2009. Does climate change explain the

Ireland. Wader Study Group Bull. 105: 42–49.

decline of a trans-Saharan Afro-Palaearctic migrant?

—, Mee, A., & Yalden, D. W. 1999. Recent fluctuations

Oecologia 159: 649–659.

in a Common Sandpiper breeding population.

Pennycuick, C. J. 1989. Bird Flight Performance. A practical

Scott. Birds 20: 44–45.

calculation manual. OUP, Oxford.

—, Holland, P. K., Mee, A., & Yalden, D. W. 2005.

Sanderson, F. J., Donald, P. F., Burfield, I. J., & van Bommel,

Comparative population dynamics of Common

F. P. J. 2006. Long-term population declines in Afro-

Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos: living at the edge.

Palearctic birds. Biol. Conserv. 131: 93–105.

Bird Study 52: 80–87.

Sauvage, A., Rumsey, S., & Rodwell, S. 1998. Recurrence

Durance, I., & Ormerod, S. J. 2007. Climate change

of Palaearctic birds in the lower Senegal river valley.

effects on upland stream macroinvertebrates over

Malimbus 20: 33–53.

a 25-year period. Global Change Biology 13: 942–957.

Sharrock, J. T. R. 1976. The Atlas of Breeding Birds in

Gibbons, D. W., Reid, J. B., & Chapman, R. A. 1993.

Britain and Ireland. Poyser, Calton.

The New Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland:

Trolliet, B., & Fouquet, M. 2004. Wintering waders in

1988–1991. Poyser, London.

coastal Guinea. Wader Study Group Bull. 103: 56–62.

Forchammer, M. C., Post, E., & Stenseth, N. C. 1998.

Yalden, D. W. 1986. Diet, food availability and habitat

Breeding phenology and climate. Nature 391:

selection of breeding Common Sandpipers Actitis

hypoleucos. Ibis 128: 23–36.

Harrington, B. A. 1999. The hemispheric globetrotting

—1992a. The influence of recreational disturbance on

of the White-rumped Sandpiper. In: Able, K. (ed.),

Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos breeding by

Gathering Angels: migrating birds and their ecology,

an upland reservoir. Biol. Conserv. 61: 41–50.

pp. 119–133. Cornell University Press.

—1992b. The Common Sandpiper population of the

Holland, P. K., & Yalden, D. W. 1991. Growth of

Ladybower reservoir complex – a re-evaluation.

Common Sandpiper chicks. Wader Study Group Bull.

Naturalist 117: 63–68.

—1993. Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos. In:

— & — 1994. An estimate of lifetime reproductive

Gibbons, D. W., Reid, J. B., & Chapman, R. A. (eds.),

success for the Common Sandpiper Actitis

The New Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland:

hypoleucos. Bird Study 41: 110–119.

1988–1991, pp. 192–193. Poyser, London.

— & — 1995. Who lives and who dies? The impact of

— & Dougall, T. W. 1994. Habitat, weather and the

severe April weather on breeding Common

growth rates of Common Sandpiper Actitis

Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Ringing & Migration 16:

hypoleucos chicks. Wader Study Group Bull. 73: 33–35.

— & — 2004. Production, survival and catchability of

— & — 2002a. Population dynamics of Common

chicks of Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos.

Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos in the Peak District of

Wader Study Group Bull. 104: 82–84.

Derbyshire – a different decade. Bird Study 49: 131–138.

T. W. Dougall, 38 Leamington Terrace, Edinburgh EH10 4JLP. K. Holland, 32 Southlands, East Grinstead, West Sussex RH19 4BZD. W. Yalden, High View, Tom Lane, Chapel-en-le-Frith, High Peak SK23 9UN

British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114

Source: http://britishbirds.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/V103_N02_P100%E2%80%93114_A.pdf

Standards in Genomic Sciences (2014) 9:821-839 Genome analysis ofstrain GrollT a highly versatile Gram-positive sulfate-reducing bacterium Jan Kuever1, Michael Visser2, Claudia Loeffler3, Matthias Boll3, Petra Worm2, Diana Z. Sousa2, Caroline M. Plugge2, Peter J. Schaap4, Gerard Muyzer5, Ines A.C. Pereira6, Sofiya N. Parshina7, Lynne A. Goodwin8,9, Nikos C. Kyrpides8, Janine Detter9, Tanja Woyke8, Patrick Chain8,9, Karen W. Davenport8,9, Manfred Rohde10, Stefan Spring11; Hans-Peter Klenk11, Alfons J.M. Stams2,12

List of diseases and conditions in meat goats. Diseases - Symptoms and Possible Treatments [ Physical/Skin ] [ Respiratory Signs ] [ Diarrhea Signs ] [ Temperature Signs ] [ Diseases & Conditions ][ Medication ] [ Poisonous Plants ] [ Symptoms ] [ Lessons Learned ] [ Home ] [ Port A Hut Distributor ] [ Contact Information ] [ Our Farm ] [ Directions to Our Farm ] [ Our Breeding Bucks ]