Microsoft word - manoshi evaluation surveys report_final

COMMUNITY HEALTH SOLUTIONS IN

BANGLADESH

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban

Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011

Scientific Report No: 118

December 2011

COMMUNITY HEALTH SOLUTIONS IN

BANGLADESH

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban

Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011

Nurul Alam

Dilruba Begum

Syed Masud Ahmed

Peter Kim Streatfield

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) and BRAC

in cooperation with

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

ISBN: 978-984-551-329-6

Scientific Report No. 118

December 2011

Published by

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b)

GPO Box 128, Dhaka 1000

Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh

Telephone: 8860523-32 (10 lines); Fax: (880-2)-8826050

Email:

[email protected] URL: http://www.icddrb.org

Printed by: Impression Printing House

This research activity was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, USA and BRAC, Bangladesh. icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and BRAC to its research efforts.

The MANOSHI project is developed by BRAC to establish a community-based health programme targeted at reducing maternal, neonatal, and child deaths and diseases in urban slums of Bangladesh. It is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation's Community Health Solutions (CHS) initiative that aims at strengthening and leveraging community organizations and individuals to be proactive in community based interventions. This five-year project is led and implemented by BRAC. icddr,b, in collaboration with the Research and Evaluation Division (RED) of BRAC provide technical assistance to the project through monitoring, evaluation and research support. This project is guided by a Technical Advisory Committee and a Technical Management Committee.

BRAC and icddr,b would like to acknowledge the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for their continued support. We are grateful to all the researchers and members of programme team for their unabated diligence and efforts. We want to extend our appreciation to all the respondents from the various communities for their wilful contributions and sincere commitment towards fulfilling this research endeavour. We also acknowledge the contributions of ACPR (Associates for Community and Population Research) for field data collection.

Technical Advisory Committee

Technical Management Committee

Dr. Abhay Bang

Dr. Abbas Bhuiya

Deputy Executive Director

Executive Director's Division

icddr,b, Bangladesh

Dr. Lynn Freedman

Dr. Peter Kim Streatfield

Director, Centre for Population Urbanization and

Averting Maternal Death and Disability (AVDD)

Columbia University, USA

Health and Demographic Surveillance Unit icddr,b, Bangladesh

Dr. Jon Rohde

Dr. Shams El Arifeen

Director, Centre for Child and Adolescent Health

International Advisory Board

icddr,b, Bangladesh

James P. Grant School of Public Health

BRAC, Bangladesh

Ms. Julienne Hayes Smith

Mr. Faruque Ahmed

Safe Motherhood Project

Health Programme

CARITAS CH-NFP, Bangladesh

BRAC, Bangladesh

Dr. Abbas Bhuiya

Dr. Kaosar Afsana

Deputy Executive Director

Associate Director

Office of the Deputy Executive Director

Health Programme

icddr,b, Bangladesh

BRAC, Bangladesh

Prof. Sameena Chowdhury

Dr. Syed Masud Ahmed

Professor and Head of Department

Research Coordinator

Obstetrics and Gynaecology Institute of Child and

Research and Evaluation Division

Mother Health, Bangladesh

BRAC, Bangladesh

Prof. Mohammod Shahidullah

Dr. Hashima-e-Nasreen

Pro-Vice Chancellor (Admin.) and Chairman

Senior Research Fellow

Dept. of Neonatology

Research and Evaluation Division

BSMMU, Bangladesh

BRAC, Bangladesh

Dr. Zafrullah Chowdhury

Dr. Jahangir Khan

Health Economist

Gono Shasthaya Kendra

Director's office of CEHS

icddr,b, Bangladesh

Dr. Kaosar Afsana

Dr. Laura Reichenbach

Associate Director

Director, Centre for Reproductive Health

icddr,b, Bangladesh

BRAC, Bangladesh

Dr. Alayne Adams

Senior Social Scientist Director's office of CEHS icddr,b, Bangladesh

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ACPR

Associates for Community and Population Research

Acute respiratory infection

Assistance for Social Advancement

Behaviour change communication

Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey

Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee

Community-based skilled birth attendants

Dhaka Metropolitan Area

Exclusive breast feeding

Expanded Programme on Immunization

International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh

Medical Assistant

Maternal, newborn and child care

NGO Non-governmental

National Institute of Population Research and Training

Poverty reduction strategy paper

Primary sampling unit

SACMO Sub-Assistant

Urban Primary Health Care

Urban Primary Health Care Project II

Vitamin A deficiency

World Health Organization

CONTENTS

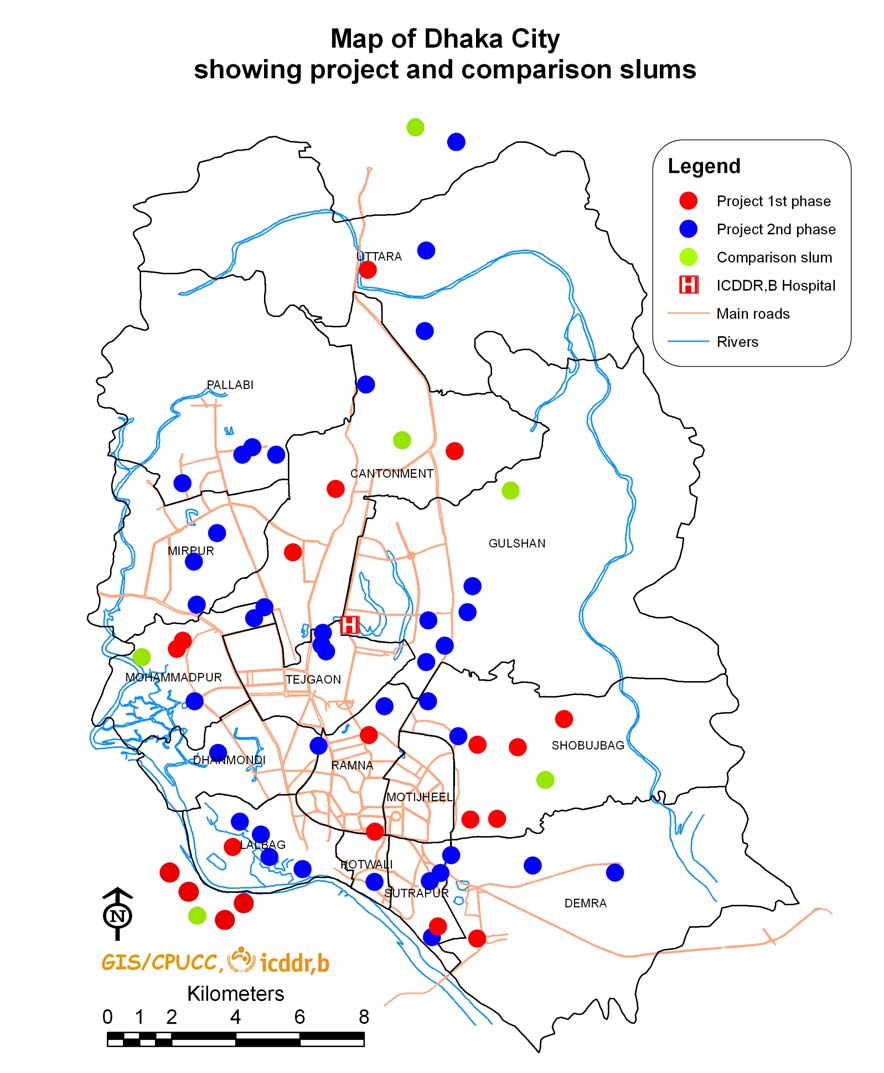

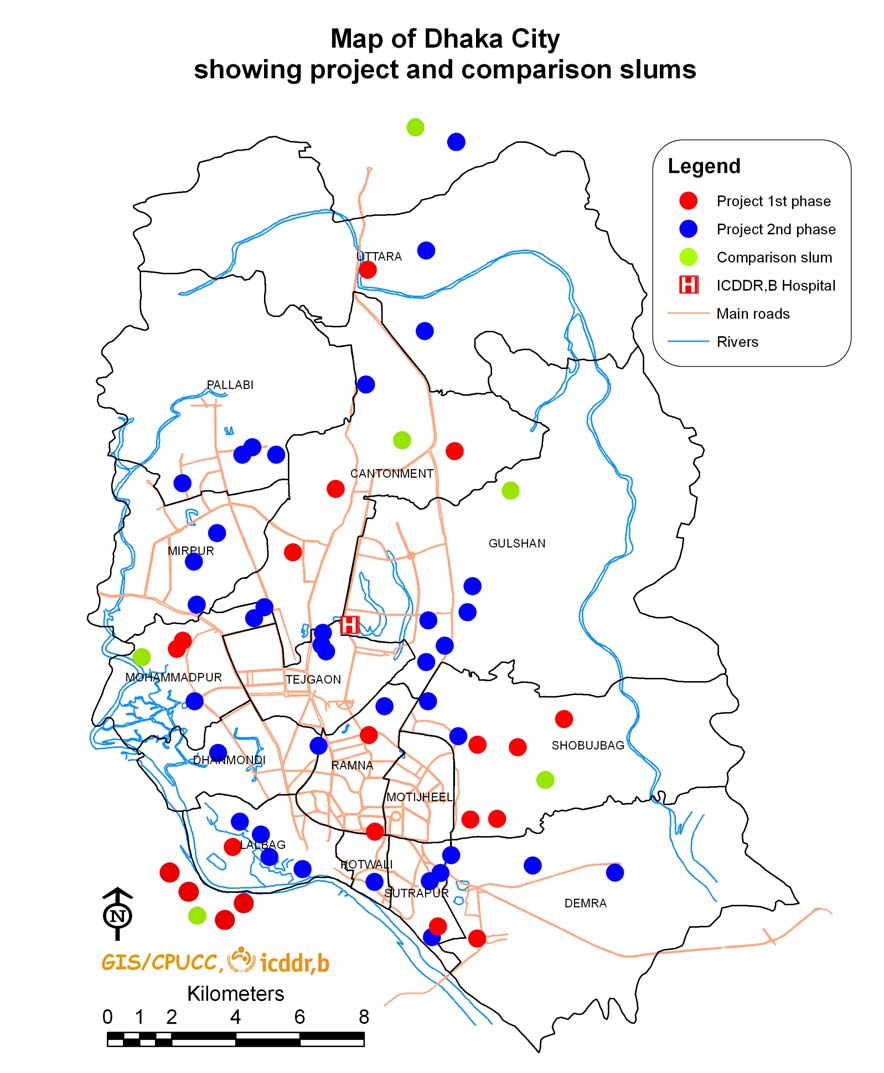

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS . i Map of Dhaka City Corporation . ix CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Health Services Delivery for Urban Poor . 1 1.2 Launching of the Manoshi Project . 2 1.3 Slums under Dhaka Metropolitan Area . 3 1.4 Methodology of Manoshi Impact Evaluation Surveys . 4 1.5 Organization of the Manoshi Impact Evaluation Surveys . 4

1.5.1 Survey Objectives and Implementation Organization . 4 1.5.2 Sampling Design of the Surveys . 5 1.5.3 Survey Questionnaire . 6

CHAPTER 2: HOUSEHOLD POPULATION AND HOUSING CHARACTERISTICS 2.1 Household Population by Age and Sex . 7 2.2 Educational Attainment . 9 2.3 Household Characteristics . 10 2.4 Household Possessions of Durable Assets . 12 2.5 Socioeconomic Status and Wealth Index . 12 CHAPTER 3: CHARACTERISTICS OF SURVEY WOMEN 3.1 Background Characteristics of Women . 15 3.2 NGO Involvement . 16 3.3 Income/Employment Activities . 17 3.4 Migration History. 18 3.5 Reproduction . 19 CHAPTER 4: KNOWLEDGER OF MATERNAL COMPLICATIONS AND NEWBORN CARE 4.1 Women's Knowledge about Maternal Health Services . 21 4.2 Mother's Knowledge on Newborn and Childcare . 25 4.3 Pregnancy Planning . 30 CHAPTER 5: PRACTICES RELATING TO MATERNAL AND NEWBORN'S HEALTH 5.1 Maternity care and services received . 32 5.2 Pregnancy Complications and Management . 54 5.3 Immediate Newborn Care . 57 CHAPTER 6: CHILD HEALTH IMMUNIZATION, MORBIDITY, AND MANAGEMENT 6.1 Immunization . 61 6.2 Children's Morbidity and Management . 62 CHAPTER 7: PERCEPTION ON DELIVERY FACILITIES AND BRAC'S BIRTHING HUT 7.1 Opinion on Local Healthcare Facilities . 65 7.2 Awareness about BRAC's Birthing Hut . 66

CHAPTER 8: POLICY IMPLICATIONS OF THE MANOSHI'S PROJECT IMPACT EVALUATION SURVEYS AND CONCLUSIONS 8.1 Status of Maternal and Child Health in Dhaka Urban Slums . 68 8.2 Policy Implications of Manoshi Impact Evaluation Surveys in 2007, 2009, and 2011 . 68 8.3 Conclusion . 71

List of Tables

Table 1

Sample-size of the baseline, midline and end line surveys for estimating

maternal, newborn and childcare indicators

Table 2.1.1a Percent distribution of the

de jure household population by age, sex and

area in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 2.1.1b Distribution of the sex ratio (= ×100) by age and area in Dhaka urban

slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of household by sex of household head, household-size 9 in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of household population aged 5 years or older by

education in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of households by housing quality in Dhaka urban

slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of households by durable assets in Dhaka urban slums,

2007, 2009, and 2011

Mean and factor loadings of standardized variables used for constructing

asset score in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by household asset quintiles by area in

Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by socio-demographic characteristics in

Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by NGO involvement and membership in

Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by employment characteristics in Dhaka

urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by residence status and migration history in

Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by number of children ever born and number 20 of children currently living in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by pregnancy terminations and place of treatment 20

for pregnancy terminations in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by knowledge about services required during 21 pregnancy in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009 and 2011

Percent distribution of women by knowledge about services required after

delivery in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by knowledge about complications during

pregnancy, place for treatment and sources of information in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by knowledge about complications during

and after delivery in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of mothers by knowledge about life-threatening health

problems of newborns during the first week after birth and place for treatment in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of mothers by essential newborn and childcare practices 27 known to them in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of mothers by knowledge about newborn and child-

feeding practices in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of mothers by knowledge about children's morbidity

and management practices in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by pregnancy planning prior to

pregnancy/childbirth in Dhaka urban slums , 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women who had live births in the last one year by

any ANC visit for the most recent pregnancy and residence status in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women with live births in the last one year by

number, timing and place of ANC visit for the most recent pregnancy in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women who gave live births in the last one year and

had 4+ ANC visits for the most recent pregnancy by parity, education, and household asset quintile in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.4: Demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with women's 4+

ANC visits for the most recent pregnancy in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women who gave live births in the last one year by

services and messages received during ANC visits for most recent pregnancy in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by residence status and place of delivery

with live births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women who had institutional delivery with live

births in the last one year by parity, level of education, and asset score in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with women's

institutional delivery with live births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by assistance, mode and procedure of

delivery with live births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.10 Percent distribution of women who had cesarean-section delivery with live

birth in the last one year by duration of residence, parity, level of education, and asset quintile in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.11 Demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with women's C-

section delivery with live births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.12 Percentage of normal and C-section deliveries by place of delivery with live 45

births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.13 Percent distribution of deliveries with live births in the last one year without

out-pocket expenditure by mode of delivery in Dhaka urban slums, 2007,

Table 5.1.14 Mean and median of the out-of-pocket expenditure by mode of delivery

with live birth in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.15 Average of out-of-pocket expenditure by institutional delivery with live

births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.16 Percent distribution of women by source of out-of-pocket expenditure and

mode and place of delivery with live births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.17 Percent distribution of women who had PNC visits with live births in the

last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.18 Percent distribution of women by PNC visit with live births in the last one

year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.19 Demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with women's PNC

for the most recent birth in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Table 5.1.20 Demographic and socioeconomic variables associated with women's 4+

ANC visits, institutional delivery, and PNC visit for most recent birth in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by complication and its management during

pregnancy with live births in the last one year in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women who gave a live birth in the last one year by

use of Misoprostol and place of delivery in Dhaka urban slums in 2011

Percent distribution of neonates born in the last one year by initial feeding

and other care in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of neonates born in the last one year by complications

and their management in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of children aged 1-4 year(s) by vaccines received at

anytime before the survey in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011.

Percent distribution of children aged 1-4 year(s) by prevalence of common

childhood illnesses in the last two weeks in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of children aged 1-4 year(s) sick with diarrhoea in the

last two weeks by management and features of diarrhoea in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women by their opinion on availability of health

services in the locality in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Percent distribution of women who had a child in the last five years by

knowledge and usage of BRAC's birthing hut in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

BRAC has launched the Manoshi project in 2007 for implementing a community-based

programme on comprehensive package of essential services in urban slums for improvement

of maternal, newborn and child health. The package included capacity development of the

community health workers and birth attendants; development of health services provisions

for pregnant and lactating women, neonates and under-five children; timely referral to quality

health facilities; community empowerment through development of women's groups; and

linkage with government (national and local), community people, and NGOs. The community

health workers and birth attendants have received training to offer antenatal, safe delivery and

postnatal care, neonatal care and childcare. The project has expanded its activities in two

phases and covered all slums in Dhaka metropolitan area (DMA) by 2009.

As part of the impact evaluation activities of the Manoshi project, three community-based

cross-sectional surveys (baseline, midline, and endline) are conducted in Dhaka urban slums

in 2007, 2009, and 2011. A two-stage random cluster-sampling was used for selecting 100

slum-clusters (50 each from the project and the comparison areas in baseline survey and 67

from the project area and 33 from the comparison area in the midline and the endline

surveys). The sample-size in the baseline survey was 2,874 [(1,284 women having infants

and 1,590 having children aged 1-4 year(s)]; the sample-size in the midline was 3608 [(1,549

women having infants and 2,049 having children aged 1-4 year(s)]; and that the endline

survey was 3,226 [(1,549 women having infants and 1,677 having children aged 1-4 year(s)].

Each survey obtained data from two groups of respondents in the project and the comparison

areas.

The baseline survey randomly selected comparison clusters around the project slums while

the midline and the endline surveys selected comparison clusters from a few non-project

slums (in Nikunja housing area, Dhaka Uddyan, and Baraid) in Dhaka city and from slum-

like clusters of impoverished households in the periphery of Dhaka city (namely Demra,

Jingira, Keranigonj, and Tongi). As such, the comparison groups of the midline and endline

surveys are not truly comparable with the project groups but provided contemporary

estimates of knowledge and practices in maternity and newborn care for women in low-

income urban households. The results of the three cross-sectional surveys conducted in 2007,

2009, and 2011 are presented below to assess changes in knowledge and practices within and

between areas over the years. Consistent difference in maternal and newborn healthcare

indicators between 2007 and 2011 in the project area compared to the comparison area could

be attributed largely to the effects of the Manoshi's project activities.

Household Population and Housing Characteristics

The sampled household populations are predominantly young, with 41-46% aged below 15 years and 45-51% aged 15-44 years in three surveys. Average household size has decreased in either area over the years. The average is 4.8 persons each in the project and the comparison areas in 2007 compared to 4.7 and 4.6 persons respectively in 2011. The percentage of the female headed households has shown a declining trend: 7% each in the project and the comparison areas in 2007 decreased to 5% each in 2011.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 i

Literacy rate (among persons aged 5+ years) was higher in 2011 compared to 2007 in the

project area only. It was, however, similar in the comparison area.

Characteristics of the Sampled Households

Almost all (99%) of the households had electricity connections in 2011 compared to 89% in

2007 in the project area. In the comparison area, the figures were 95% in 2007 and 96% in

2011.

Access to sanitation (measured in terms of possession of modern toilet or water-sealed

latrine) has increased to 73% in 2011 from 33% in 2007 in the project area. In the comparison

area, it increased to 68% in 2011 from 59% in 2007.

More households had piped water inside dwelling houses in 2011 compared to 2007 in the

project area (65% versus 56%) and the comparison area (75 versus 65%).

Proportionately, more households had roofs, walls, and floors made of cement/concrete in

2011 than in 2009 and 2007 in both areas.

More households had more durable assets, such as wardrobe, table, chair, television, and

mobile phones (but not watch, radio, bicycle, and rickshaw/van) in 2011 than in 2009 and

2007 in either area, suggesting an improvement in quality of living over the years.

Characteristics of the Sampled Women

Women with complete primary education (class 5 or higher) were higher at 59% in 2011 compared to 34% in 2007 in the project area. In the comparison area, the figure was 48% in 2011 compared to 49% in 2007. Access to mass media (measured in terms of reading newspapers, listening to radio or watching television at least once a week), with prominence of television over newspapers and radio being universal in either area. Women's participation in labour force (indicated by employment at the survey time) decreased from 25% in 2007 to 17% in 2011 in the project area. In the comparison area, participation has decreased from 26% in 2007 to 21% in 2011. Their involvement in NGO activities decreased in the project and the comparison areas over the years (from 23% each in 2007 to 9% and 13% respectively in 2011). More than half of the women in either area came from rural areas, and the share shrank over the years. Mean number of children ever born to the women was lower in the project and the comparison areas in 2011 (2.1 and 2.2, respectively) than in 2007 (2.6 and 2.4 respectively).

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 ii

Women's Knowledge about Maternity Care

Knowledge about requirements for antenatal care and TT vaccination during pregnancy was

universal (>97%) in each area and year. Importance of iron supplementation during

pregnancy was known to more than 91% of the women in either area.

Knowledge about government recommendation of 4+ ANC visits increased from 45% in

2007 to 59% in 2011 in the project area. In the comparison area, it increased from 50% in

2007 to 52% in 2011.

Knowledge about requirements of postnatal care (PNC) was high (83% or more) in either

area but awareness of the recommended 3+ PNC visits decreased over the years: from 40%

each in 2007 to 28% each in 2011 in both areas.

Knowledge about requirements of vitamin A intake and iron supplementation after delivery

was as high as 86%. It increased at a higher rate in the project area than in the comparison

area over the years.

Knowledge about life-threatening pregnancy complications/illnesses (except lower

abdominal pain and reduced foetal movement) improved in either area over the years. In

2011, the complications were known to 5-15% more women in the project area than in the

comparison area.

For treating pregnancy complications/illnesses more women opt for government hospitals

(59% and 69% respectively), followed by private clinics (30% and 33% respectively) and the

NGO health centres (18% and 21% respectively) in either area in 2011. BRAC delivery hut is

opted by 30% in 2011 compared to 2% in 2007 in the project area and 3% in the comparison

area in 2011.

Knowledge about life-threatening post-delivery complications increased more in the project

area than in the comparison area over the years.

For managing such complications, more women in either area in 2011 opted for government

hospitals (77% and 80% respectively), followed by private clinics (32% and 34%

respectively) and the NGO health centres (24% and 16% respectively).

Women's Knowledge about Newborn and Child Health Problems

When asked about newborn's life-threatening health problems in 2011, women in the project

area mentioned more frequently: difficult or fast breathing, asphyxia, jaundice, and

convulsions (70%, 49%, 39%, and 37% respectively) as health problems compared to women

in the comparison area (65%, 48%, 27%, and 30% respectively).

For treating these problems, more women in either area in 2011 opted for government

hospitals (78% each), followed by private clinics (42% each) and NGO health centres (16%

and 11% respectively).

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 iii

Knowledge relating to drying newborn thoroughly, wrapping with warm clothes, and feeding

colostrums improved faster over the years in the project area than in the comparison area.

Mothers' knowledge about requirements of vaccination right after birth and vitamin A for

under-five children was universal in either area.

Knowledge about newborn's first feeding substantially improved―more in the project area

than in the comparison area over the years.

While knowledge about time of initiation of breastfeeding (within one hour) was almost

universal (>90%) in either area, knowledge of duration of exclusive breastfeeding (up to 6

months) improved more in the project area―from 73% in 2007 to 96% in 2011 than the

comparison area; this improved from 68% in 2007 to 91% in 2011.

Two in every five women knew symptoms of acute respiratory infection (ARI) and did not

improve in either area over the years.

Knowledge of giving packet-saline to children suffering from diarrhoea was universal (95%

or more) but giving ‘more-than-usual food to children with diarrhoea' was known to three in

five women in either area.

For treating diarrhoea and pneumonia in children, the most preferred healthcare provider in

either area in 2011 was qualified doctor (87% in the project area and 83% in the comparison

area).

More women in the project area than in the comparison area in 2011 made pregnancy

planning (91% versus 80%), made plan for assistance during delivery (80% versus 77%

respectively) and saved money to face extra expenses relating to childbirth (77% versus

72%).

Use of Maternal Health Services

The percentage of women having any ANC visit during the last pregnancy as well as average

number of ANC visits increased more in the project area than in the comparison area over the

years

Coverage of government-recommended ‘4 or more ANC visits' increased in the project area

from 27% in 2007 to 42% in 2009 to 52% in 2011 but not in the comparison area (36% in

2007, 34% in 2009, and 36% in 2011).

Coverage of 4 or more ANC visits was higher for births of the first-order than four or higher

order, for women with secondary education than no education; and the least poor than poorest

households in either area. Differentials in ANC coverage by birth-order, education and

economic groups decreased in the project area but not in the comparison area over the years.

Places to get ANC in the project area in 2011 were BRAC birthing (or delivery) hut (35%),

followed by private clinics (17%), and NGO health centres (14%). In the comparison area,

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 iv

places included government hospitals (25%), followed by NGO health centres (21%), and private clinics (16%) in 2011. ANC services that the women received were of higher quality in the project area than in the comparison area. Measurements of weight and height and examination of abdomen (67% versus 59%, 11% versus 19% and 70% versus 52% respectively) were more frequent in the project area compared to the comparison area in 2011. During ANC visits in 2011, more women in the project area compared to the comparison area received advice on 'proper diet', ‘taking rest', ‘not to lift heavy items', and ‘intake of iron supplement' during pregnancy (72%, 64%, 49%, and 17% respectively). The percentage of institutional delivery (including BRAC birthing hut) increased more in the project area than in the comparison area over the years; this increased to 59% in 2011 from 15% in 2007 in the project area than in the comparison area; this increased to 28% in 2011 from 25% in 2007. In the project area, 23% of the deliveries took place in the BRAC delivery hut in 2011 compared to just 1% in 2007, or 3% in the comparison area in 2011. Short duration of living in enumeration slum and history of migration from rural or urban areas were associated with lower percentage of institutional delivery in either area. Likelihood of institutional delivery was higher for births of the first-order than four- or higher-order, for women with secondary education than no education, and the least poor than poorest households in either area. Institutional delivery became more equitable (measured in terms of difference between sub-groups of birth-order, education, and asset score) in the project area than the comparison area over the years. The caesarean section (C-section) rate increased to 24% in 2011 from 6% in 2007 in the project area, and in the comparison area; this increased to 14% in 2011 from 11% in 2007. C-section varied widely by household asset quintile in both areas. The economic differential in C-section was lower in the project area than in the comparison area. Type of institution was related to C-section; more than two-thirds (69-70%) of the deliveries in private clinics had C-sections compared to half (53-54%) of the deliveries in public hospitals in 2011. Out-of-pocket expenditure was lower for normal vaginal delivery but not for C-section in the project area than in the comparison area. In 2011, normal delivery at home in the project area, on an average, cost Taka 1,452; normal delivery at institution cost Taka 2,181 and C-section cost Taka 12,714. The respective averages in the comparison area were Taka 1,821, Taka 3,823, and Taka 11,289.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 v

Use of Misoprostol for prevention and treatment of postpartum bleeding was more frequent

(53% versus 27%) in the project area than in the comparison area in 2011.

Deliveries assisted by medically-trained persons, such as doctors (28%), BRAC midwife

(23%), and nurse/midwife/family welfare visitors (9%) were higher in 2011 than in 2007

(8%, 1%, and 5% respectively) in the project area. In the comparison area, the medically-

trained persons were doctors (17%) and nurse/midwife/family welfare visitors (8%) in 2011

and comparable with 2007 (14% and 10% respectively).

More women received PNC after delivery in 2011 than in 2007 (66% versus 28%) in the

project area and also in the comparison area (33% versus to 40%). Coverage of recommended

three or more PNC visits was higher (20% versus 8%) in 2011 than in 2007 in the project

area but not in the comparison area (9% versus 13%).

Short duration of living in enumeration slum or history and migration from rural or other

urban areas was associated with lower coverage of PNC visits in either area.

Coverage of PNC has been higher for births of the first-order than four- or higher-order,

women with secondary education than no education and the least poor than the poorest

households in either area.

PNC services became more equitable (indicated by decline in gaps between sub-groups of

birth-order, education, and asset quintiles) in the project area than the comparison area over

the years.

Institutions that were used more often for PNC included BRAC delivery huts (24%), private

clinics (15%), and government hospitals (15%) in the project area in 2011 compared to 2%,

4%, and 7% respectively in 2007. In the comparison area, institutions for PNC were

government hospital (15%), private clinics (8%), and NGO clinics (5%) in 2011 compared to

10%, 11%, and 9% respectively in 2007.

More common self-reported pregnancy complications were oedema of hands/feet, abdominal

pain, severe headache/blurry vision, and high fever in the project and the comparison areas in

2011.

For treatment of pregnancy complications, women more often used NGO health centres,

private clinics, and government hospitals in either area.

Immediate Newborn Care Practices

Colostrum as pre-lacteal feed after birth was given more often in the project and the

comparison areas in 2011 (77% and 61% respectively) than in 2007 (36% and 43%

respectively). Over the years, use of honey and sugar/glucose water as pre-lacteal feed

reduced at faster rates in the project area than in the comparison area.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 vi

The percentage of breastfeeding within an hour of birth increased in both areas; the rate of

increase was higher in the project area (from 50% in 2007 to 71% in 2011) than in the

comparison area (from 49% in 2007 to 62% in 2011) over the years.

Practice of giving bath just after birth reduced more in the project area (from 55% in 2007 to

16% in 2011) than in the comparison area (from 45% in 2007 to 29% in 2011) with

simultaneous increase in giving bath within third day to one week after birth in the project

area only.

The practice of shaving baby's hair within the third day to one week after birth was very high

in either area with a faster declining trend in the project area (from 91% in 2007 to 72% in

2011) than in the comparison area (from 85% in 2007 to 77% in 2011).

Health check-up of neonates increased at a faster rate (from 40% in 2007 to 67% in 2011) in

the project area but not in the comparison area (from 50% in 2007 to 39% in 2011) over the

years.

Two-thirds of the neonates had no reported illness or complications in either area each year.

Illnesses in order of prevalence were fever, followed by cough, difficult breathing, jaundice,

and skin rash/pustule in either area.

Places for treating neonatal complications were private clinics, government hospitals and

pharmacies in either area. Frequency of using pharmacy was lower in the project area than in

the comparison area (4% versus 8%) in 2011.

Child (aged 1-4 years) Health Services

Complete vaccination (BCG, three doses of DPT and Polio, and Measles) coverage increased

more in the project area (from 38% in 2007 to 79% in 2011) than in the comparison area

(from 38% in 2007 to 69% in 2011) over the years.

Distribution of childhood illnesses was similar across areas. The most common childhood

illnesses were fever, followed by cough, difficult breathing, and diarrhoea. Prevalence of

acute respiratory infection (ARI) declined a little in the project area (from 11% in 2007 to 8%

in 2011) but not in the comparison area (from 11% in 2007 to 10% in 2011).

Seeking treatment was less frequent for diarrhoea than for ARI. Common places for treatment

of ARI and diarrhoea were pharmacies, private clinics, and government hospitals in either

area.

Perception on Local Delivery Facilities and BRAC Birthing Hut in Project Area

Women's knowledge relating to healthcare and delivery facilities in their localities increased

more in the project area (from 53% in 2007 to 94% in 2011) than in the comparison area

(from 45% in 2007 to 63% in 2011).

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 vii

Health facilities mentioned more frequently in 2011 in the project area were BRAC delivery hut (86%), NGO-operated health centre (35%), and private clinic (19%) and that in the comparison area were private clinic (43%) and NGO health centre (35%). Aspects of healthcare and facilities that satisfied women were good behaviour of the staff, availability of drugs and supplies, effective treatment, and less waiting-time in either area. Women's knowledge about the existence of BRAC birthing huts in their localities increased from 25% in the 2007 to 90% in the project area. By 2011, 83% of the women became aware of availability of ANC, 59% were aware of skilled delivery assistance, 42% were aware of delivery care, and 27% were aware of newborn care in a birthing hut. Most common sources of information on services a deliver hut offers were BRAC staff (66%), followed by own experience (24%), and neighbour/friend (17%). Registration with BRAC birthing huts increased from 7% in 2007 to 62% in 2011 for accessing antenatal check-up (59%), skilled delivery assistance (42%), delivery care (32%), and newborn care (18%). In conclusion, the project has been able to improve practices more than knowledge on maternal and newborn care and to reduce the inequalities in practices over the years. Lessons learnt from this intervention must be used effectively to further develop and improve the MNCH services in order to move towards a sustainable scale-up at the national level.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 viii

Figure 1:

MAP OF DHAKA CITY CORPORATION

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 ix

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Urbanization is an inevitable and unavoidable feature in a society's development process.

Bangladesh, along with other Asian countries, has been experiencing rapid urbanization in

recent decades (1, 2, 3). The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics―the national statistical

organization of the government―projected that fifty percent of the Bangladesh population

would be living in urban areas by 2035, and the majority would be living in Dhaka city (4).

The increase in urbanization is due to (a) rural- urban migration, (b) geographical increase in

urban territory, and (c) natural growth of population in urban area. The rural-urban migration

contributes most to rapid urbanization. Distant factors accelerating the rural-urban migration process are natural disasters, high

population density, high population growth, small farm-size, landlessness, and poor

communication infrastructure (5). Natural disasters, such as cyclone, flood, river erosion or

drought affect thousands of rural households every year. Frequent flood and river erosion

damage the rural infrastructure. Overall, population density is far higher than any other

country that is not a city state (4). Agricultural land is virtually saturated. High population

growth continuously shrinks availability of per-capita agricultural land, and makes 1 percent

of it into non-agricultural land every year (6). All these together accelerate the ongoing

process of increasing number of landless households and diminish job opportunities in rural

In an era of globalization, economic and labour migration, both internal and international, is

on the rise. Migration is an option to escape from deteriorating economic and social

conditions at place of origin. Labour and economic migration from rural to urban areas in

Bangladesh is predominantly due to shortage of agricultural land, small farm-size, surplus

agricultural labour, the seasonal nature of agricultural work, and occasional natural disasters.

The poor lack the financial and social resources required to live there. Many, already

destitute, do not have a decent place to live. To cope with the situation they migrate to towns

and cities in search of employment or scope of earning (7), indicating a clear link between

rural poverty, migration and urbanization. The urban poor are largely rural migrants and find

shelter in overcrowded slums with inadequate sanitation and other civic facilities. Migration

and health connection is bidirectional and in the dynamic perspective it gives us the

opportunity to look at it both ways. Altogether, rapid urbanization in Bangladesh raises new

challenges for parties aiming to serve the poor and address poverty.

Most migrants from rural areas come to the already over-crowded Dhaka city, with around

one-third living in informal settlements under unhealthy and unsafe conditions (8).

Implications of unbridled urban growth and proliferating slums are high unemployment and

underemployment, overcrowded housing, deterioration of environmental conditions,

inadequate supply of clean water, high incidence of diseases and poverty and overcrowding

in schools and hospitals. The other implications are overloading in public transports and

increase in traffic jams, road accidents, violence, crimes, and social tension. All these make

the conditions more unhealthy and unsafe and challenge heavily the capacity of urban centres

to cater for the basic civic needs of newcomers.

1.1 Health Services Delivery for Urban Poor

Compared to rural primary healthcare (PHC) infrastructure, the urban PHC infrastructure that could help improve the health of the urban poor is underdeveloped (9, 10). Although the urban population has been increasing rapidly for a longer period of time, the government and external donor agencies have started addressing urban PHC problems only in the last decade.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 1

Under the present PHC system, slum-dwellers in metropolitan cities of this country need to seek treatment and care directly from tertiary-level hospitals and facilities, which involves time, money and, sometimes, negligent and incompliant behaviour on the part of the care-seekers. For improving the health of the urban poor, particularly women and children through improved access and provision of health services in urban areas, the Urban Primary Health Care (UPHC) Project was initiated in 1998 (9). The project established 142 PHC delivery centres in the four major cities of the country, including 60 solely in the Dhaka City Corporation (DCC) for delivering good quality preventive, promotional and curative services. DCC has signed the contract with selected competitive NGOs for delivering a package of essential health services and comprehensive emergency obstetric care (EOC) in 10 defined partnership areas, linking contract payments to improve health of the population in the project area. The interim poverty reduction strategy paper (PRSP) and the targets set on poverty reduction reflect the government's commitment to achieving the MDGs by strengthening urban PHC, especially for the poor.

The second project called ‘Urban Primary Health Care Project II (UPHCP-II)' covers the six city corporations and five selected municipalities of Bangladesh for the period 2005-2011 with:

focus on providing a package of essential primary health services with an emphasis on preventive intervention, giving priority to maternal and child health;

expand the role of the private sector, including NGOs in the provision of health, nutrition and population services;

take gender, equity, poverty and developmental issues into account in designing and provision of services;

expand cost recovery and improve efficiency of resource utilization in the public sector;

involve beneficiaries in the management of healthcare;

emphasize on the sustainability and environmental issues; and

endeavour to provide one-stop shopping for health and population services (11)

The Health, Nutrition and Population Sector Project (HNPSP), currently, a new

HPNSDP (2011-2016) of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of

Bangladesh embodies all of these and adds a few new dimensions, e.g. risk-sharing and risk-

spreading to address catastrophic illnesses and piloting of demand-side financing in different

forms and decentralization of decision-making by the lower level managers (12). The project

aims to contribute towards achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

undertaken at the Millennium Summit 2000 of UN.

1.2 Launching of the Manoshi Project

The slums have a disproportionate share of the poor and have worst health status originating

from lack of basic social and public-health services. BRAC has designed an intervention in

2007, called Manoshi, a five-year project to improve maternal, newborn, and child health in

the urban slums of Bangladesh through the implementation of a community-based

programme on comprehensive package of essential health services. The project focused

primarily on enhancing the empowerment of communities, e.g. women to develop a system

for the continuum of care for mothers and babies with an essential service package of

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 2

interventions. The components of the project include: capacity development of the

community health workers and birth attendants to offer basic maternity services; health

service provision for pregnant and lactating women, neonates and under-five children; timely

referral to quality health facilities; community empowerment through development of

women's groups; and linkage with government, local government, community people and

NGOs. The community health workers are to visit households and identify pregnancies and

follow them up no matter where women seek care from BRAC delivery hut. The project has

gradually expanded its activities to all the slums under the Dhaka City Corporation and

peripheral unions under the metropolitan area by 2009 and to all the slums in all other city

corporation areas by 2011.

The impact evaluation surveys aim to examine how effective is the Manoshi project in

improving knowledge and practices relating to maternal and newborn care in slums of Dhaka

city. The results will help to have a distinct vision and clear strategies to address maternal,

newborn and child healthcare in urban slums.

1.3 Slums under Dhaka Metropolitan Area

The Dhaka Metropolitan Area (DMA), with an estimated population of 9.1 million in 2005,

comprises area under Dhaka City Corporation (DCC) and adjoining areas totalling 306 sq.

kilometres. The 2005 Slum Census of Urban Bangladesh identified 4,966 slum clusters in

DMA with a total slum population of 3.4 million (37.4% of the total population in

DMA)―more than double the slum population counted in 1996 (3).

The 2005 slum survey also identified conspicuous growth of slums in peripheral and

suburban areas of Dhaka city. In the central areas of the city, slum concentrations are

relatively sparse compared to the periphery. The major slum concentrations in DMA are as

follows:

• Eastern fringe of the city, along the border of the city corporation:

Khilket, directly opposite to the Dhaka Airport Badda-Satarkul area, in the vicinity of the Gulshan and Baridhara residential areas Area between Meradia and the Kamalapur Railway Station

• Western fringe of the city:

Kamrangir Char on the bank of the river Buriganga, just outside the DCC border Hazaribagh and West Mohammadpur, along the western embankment Mirpur

The single largest concentration of slums is in Kamrangir Char, having a slum population of 265,000. The largest single slum in Dhaka city is Korail in Mohakhali near Gulshan, with more than 100,000 people (3).

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 3

1.4. Methodology of Manoshi Project Impact Evaluation

Study Design: The target populations of the Manoshi project are: (a) pregnant women, and

(b) mothers of newborn and child. The impact evaluation surveys targeted mothers with

infant and mothers with 1-4 years old child, and followed the six-cell (baseline, midline and

endline surveys in the project and comparison slums) study design to assess the effects of the

project on knowledge and practices relating to maternal health services and newborn care in

urban slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Impact Surveys: The major challenge for the impact evaluation of the Manoshi project

activities is the lack of non-project slums for follow-up to control for secular changes. BRAC

has expanded the Manoshi project in two phases and covered all slums (except a few) in

DMA by 2009. The first phase is implemented in Gulshan, Shyampur, Kamrangir Char,

Shabujbag, Mohammadpur, and Uttara – these constituted the project area. The comparison

slums are chosen around the project slums. These are Badda, Hazaribagh, Jatrabari, Khilkhet,

Meradia, and Mirpur, constituting the comparison area. The sample-size of the project and

the comparison groups in the baseline survey 2007 was equal.

The second phase of the Manoshi project covered all slums in DMA, except for slum

households in Nikunja Housing area in Khilkhet Thana, Dhaka Uddyan in Adabar Thana and

Baraid in Badda Thana. Lack of enough households to make the comparison groups forced

us to make the project and the comparison groups unequal; 2:1.

Limitations of the Impact Study: In absence of enough slum households without Manoshi

project activities in the DMA, the comparison group included a few slums in DCC and a

number of slums selected from periphery of DCC. Arguably, the comparison and project

slums were dissimilar in terms of access to health facilities, tenant status and economic

condition. Nonetheless, such a comparison group is better than having none at all, to control

for secular changes due to non-project and extraneous factors. Analysis, however, controls

the effects of some of the factors that differentiate the project group from the comparison

group.

1.5 Organization of the Manoshi Impact Evaluation Surveys

1.5.1 Survey Objectives and Implementing Organization

Impact evaluation surveys in 2007, 2009, and 2011 collected data on knowledge, perception,

and practices relating to maternity care, newborn, and childcare of women having under-five

child(ren) living in slums in the DMA. Sample-size, sampling design, and selection of

primary sampling units were determined by icddr,b and shared with the Technical

Management Committee of the project. All three surveys were implemented by a private

survey organization entitled "Associates for Community and Population Research (ACPR,

email: [email protected])". The overall objective of the surveys was to estimate changes

(improvements) over the years in knowledge and practices relating to maternal, newborn and

childcare in the project slums compared to the comparison slums. The specific objectives

were:

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 4

• Assess levels of women's knowledge and perceptions relating to antenatal care,

delivery care and postnatal care, and care of neonates and sick children living in the project and comparison areas in 2007, 2009, and 2011.

• Assess levels of women's practices relating to maternity care, and care of neonates

and sick children living in the project and comparison areas in 2007, 2009, and 2011.

• Assess the effects of the Manoshi's project on women's knowledge and practices

relating to antenatal care, delivery care and postnatal care, and care of neonates and sick children, controlling for socioeconomic and demographic factors.

• Assess socioeconomic differentials (i.e. equity) in women's practices relating to

maternity care, and care of neonates in the project area compared to the comparison area over the years.

1.5.2 Sampling Design of the Surveys

The two-stage random-cluster sampling was followed in all three surveys (the baseline survey

2007, the midline survey 2009, and the end line survey 2011) for selecting sampling units.

The first stage was the random selection of clusters (of slums) by PPS (probability

proportional to size measured in terms of number of households), and the second stage was

selection of households with eligible women. As mentioned before, a few slums in the DMA

outside the purview of the Manoshi's project are not enough to make a comparison group of

equal size to the project group, the sample-size for the comparison group was made half the

size of the project group (the project sample ratio was 1:2) in the midline survey 2009 and the

endline survey 2011.

Sample-size: The sample-sizes of the project and comparison groups in three surveys are

shown below (Table 1). Indicators that were used in estimating the sample-size are antenatal

care visits (4 or more), facility delivery, any postnatal care visit, child immunization

coverage, and sickness care. The sample-size of the baseline survey 2007 was 2,874, the

midline Survey 2009 was 3,608, and the endline survey 2011 was 3,777 women.

Table 1. Sample-size of the baseline, midline and endline surveys for estimating maternal,

newborn and childcare indicators

Baseline survey 2007 Midline survey 2009 Endline survey 2011

Mothers with infant Project

Comparison 612 536 562 Mothers with 1-4 year old child Project

Comparison 783 667 720

Total number

Selection of the sampling units: Manoshi project prepared a list of slums and divided them

onto blocks (or clusters), each of 175-200 households (a working unit of a BRAC community

health worker called ‘Shashthya Sebika'). This list served as sampling frame for the first

stage of sampling 100 clusters (50 from the project area and 50 from the comparison area) for

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 5

the baseline survey 2007. The numbers of clusters in the project and the comparison areas

were 67 and 33 respectively in the midline survey 2009 and the endline survey 2011. Samples

of the intervention groups of the midline and the endline surveys were selected

proportionately from slums covered in the 1st and 2nd phases of the Manoshi project. The

project clusters consisted of 32 from the first phase and 35 from the second phase. The

comparison sample included some clusters of impoverished households in Demra, Jingira,

Keraniganj, and Tongi―the outreach of the Manoshi's project to serve as comparison group.

The second stage of the sample selection was the selection of households with mothers

having infants or children of 1-4 year(s). A household listing operation was carried out to

update the list and identify households with mothers of infant or child aged 1-4 years in each

selected cluster. The resulting lists of the households served as sampling frame for selection

of households with mothers for interview. The required number of mothers of infants and 1-4

year old children was selected in each cluster through random systematic sampling.

1.5.3 Survey Questionnaire

The baseline questionnaire with some modifications was used in the midline and the endline

surveys. Modifications are inclusion of a few variables: ‘date of start of the activity of the

BRAC delivery centre in the catchment slums', ‘use of Misoprostol tablets after delivery',

and ‘exposure to the Manoshi project'.

Data analysis: Both bivariate and multivariate analyses were carried out to assess changes or

trends in measurable indicators of maternity and newborn care in the project and the

comparison areas over the years. Bivariate analysis shows percentage, rate or mean of the

indicators for different categories of socioeconomic and demographic factors within the area

over the years. Multiple logistic regression models estimate time trends (in terms of odds

ratio) in the indicators and their associations with different socioeconomic and demographic

factors within the area. The dose-response relationship (i.e., the longer the exposure to the

project the higher is the rate of change in measurable maternal and newborn care indicators)

is also used in assessing the trends.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 6

CHAPTER 2: HOUSEHOLD POPULATION AND HOUSING

This chapter presents information on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the

household populations of the baseline survey 2007, the midline survey 2009, and the endline

survey 2011, including age, sex, and marital status (for members aged 10 years or more),

pregnancy status (for married female members of the household), and educational attainment

(for members aged 5 years or older). The chapter also describes the conditions of the

households in which the survey populations live, including source of drinking-water,

sanitation facilities, availability of electricity, housing construction materials, possessions of

household durable goods, and ownership of homestead land. Data on household durables and

drinking-water source, sanitation facilities, quality of housing materials are used in creating a

composite indicator of household economic status called the wealth index.

The definition of household has been the same in the three surveys. A household is defined as

a person or a group of related and/or unrelated persons who usually live in the same dwelling

unit(s), who have common cooking and eating arrangements, and who acknowledge one adult

member as a head of the household. A member of the household is defined as any person who

usually lives in the household. This definition is consistent with the Demographic and Health

Survey (DHS) definition.

The characteristics of the household population are analyzed based on the de jure population

while household characteristics are presented based on the de facto population, in order to

maintain comparability of these results with other DHS reports. Tables present results of the

surveys to highlight changes in each area over time.

2.1 Household Population by Age and Sex

The age-sex distribution of the population from sampled households of the three surveys in

2007, 2009, and 2011 is shown in Table 2.1.1 and further illustrated by sex ratios ( ×100) in Table 2.1.1a. The age distribution shows a young population age-structure with more than 42% of the population under 15 years of age and more than 45% aged 15-44 years in the project and the comparison areas. As expected, one-fourth of the people are children less than five years of age.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 7

Table 2.1.1a. Percent distribution of the de jure household population by age, sex, and area in

Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

26.3 26.1 25.2 25.8 25.8 24.4 25.0 26.2 26.8 25.1 26.8 25.7

19.8 15.7 16.5 19.7 16.7 16.8 19.1 19.0 17.2 18.4 18.3 18.5

26.3 28.2 27.1 10.2

25-34 21.0 26.2 26.8 17.4 17.9 19.3 23.2 26.1 25.6 17.1 16.4 17.5 35-44 13.3 14.2 13.2 5.2

45-59 6.0 5.3 5.4 4.0

% 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

100.0 100.0 100.0

3078 4861 5354 3183

3095 2496 2697

The overall sex ratio is below 100.3 – the national estimate, revealing that females outnumber males in each area and year. For age-group 15 to 24 years, the female population in urban slums of Dhaka is markedly larger than the male population and for age-groups 25 to 44 years, the male population is larger than the female. This is expected as slums are the major residing places of migratory young males looking for earning opportunities in the transport, construction, and manufacturing, and young females in manufacturing and ready-made garments sectors.

Table 2.1.1b. Distribution of the sex ratio ( ×100) by age and area in Dhaka urban

slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

Age-group

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

117 140 136 132 153 140

249 267 281 249 282 288

145 122 92 113 132 103

141 135 142 115 134 126

all 97 96 98 97 97 95

In Bangladesh, most households are ‘male-headed', and so are the households in slums (Table 2.1.2). Only 4-7% of the households are headed by females, and the percentage has declined over the years in either area. The three-fourths of the households consisted of 3 to 5 members in each area and year. The average household-size is slightly lower in 2011 (4.7

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 8

persons in the project area and 4.6 in the comparison area) than in 2007 (4.8 persons each in the project and the comparison areas).

Table 2.1.2. Percent distribution of household by sex of household head, household-size in

urban slums of Dhaka, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

Sex of household head

Number of household members

Number of households

Mean household-size

2.2 Educational Attainment

Studies have shown that education is one of the major socioeconomic factors that influence a

person's behaviour and attitudes and has a significant effect on access to health services. In

general, the higher a person's education level, the more knowledgeable s/he is about the use

of health services, family planning methods, and hygiene practices. For all household

members aged 5 years or older, data were collected on the level of education last attained and

the highest class completed. Table 2.2.1 shows the percent distribution of household

population aged 5 years or older living in slums by educational attainment in 2007, 2009, and

2011. Educational attainment in terms of ‘ever attending school/madrasah' and ‘highest class

passed' is higher in 2011 than in 2007 in the project and the comparison areas (68-72%

versus 56-65%). Other than secular schools, percentage of household members attending

madrasah (Islamic faith schools), non-formal (under Government's Mass Literacy Project)

and non-institutional (vocational training) schools was very low each year. Educational level

of class 10 or more in the project area in 2011 was more than double (9%) that in the project

area in 2007 (3%). In the comparison area, this was lower in 2011 than in 2007 (4% versus

8%).

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 9

Table 2.2.1. Percent distribution of household population aged 5 years or older by education

in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Ever attended educational

Project area

Comparison area

institution and class passed

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

Ever attended school/madrasah

Type of school attended

Non-institutional 0.5

Level of education (class passed)

Primary incomplete

Primary complete

Secondary incomplete

Secondary complete or more

Total number

2.3 Household Characteristics

The ever-increasing number of landless households and diminishing job opportunities in the

rural areas are pushing people to migrate towards towns and cities in search of employment.

They, already destitute, do not have a decent place to live in their places of origin. They find

shelter in overcrowded slums with inadequate sanitation and other decrepit civic facilities.

The three surveys in 2007, 2009, and 2011 collected data on certain characteristics of

households, including the source of drinking-water, type of sanitation facility, main housing

materials, and access to electricity. These physical characteristics of a household are

important because they are used in assessing the general well-being and socioeconomic status

of the household members.

Table 2.3.1 presents the percent distribution of households by their characteristics in urban

slums of Dhaka in 2007, 2009, and 2011. The percentage of households with electricity

connections was higher (99%) in 2011 than in 2007 (89%) in the project area. In the

comparison area, this was 96% in 2011 compared to 95% in 2007. Availability of piped water

inside dwelling was higher in 2011 than in 2007 in the project area (65% versus 56%) and in

the comparison area (75% versus 65%). Possession of modern toilet or water-sealed slab

latrine was higher in 2011 than in 2007 (73% versus 33% in the project area and 68% versus

59% in the comparison area). In the 2007, 2009, and 2011 surveys, jhupri type of dwellings

(makeshift dwelling of low height and built with flimsy, temporary materials like polythene,

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 10

board, etc.) accounted for 1-2% of the sampled households. Most of the slum households had tin-roof, cement/concrete or tin walls, and cement floor in the project and the comparison areas. Compared to the 2007 baseline survey, more households had roofs, walls, and floors made of cement/concrete in the project and the comparison areas in 2011.

Table 2.3.1. Percent distribution of households by housing quality in Dhaka urban slums,

2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

Housing quality

Electricity connection

Source of drinking-

water

Piped inside dwelling

Piped outside dwelling

Sanitation facility

Water-sealed/slab

13.3 16.5 28.8 17.7 21.4

latrine Pit-latrine 40.8

Open latrine/bush/field

Pond/tank/canal/river 1.9 0.3 0.3 0.4 1.3

Type of main dwelling

Main roof material

Main wall material

Floor material

Total number

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 11

2.4 Household Possessions of Durable Assets

Data on household's ownerships of selected durable assets were collected in 2007, 2009, and

2011. Some of these are used in generating a wealth index. The percent distribution of

households that possess various durable goods in the project and the comparison areas in

2007, 2009, and 2011 is shown in Table 2.4.1. Overall, ownerships of durable assets, except

for radio and bicycle, were more common in 2011 than in 2007 in either area. In 2011,

ownerships were more common in the project area than in the comparison area. More

households owned a mobile phone in 2011 than in 2009 and 2007, when more households

owned a radio in either area.

Table 2.4.1. Percent distribution of households by durable assets in Dhaka urban slums,

2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

Household assets

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

Almirah/wardrobe 31.3

Chair/bench 26.6

Clock/watch 50.0

Rickshaw/van 6.1

Total number

2.5 Socioeconomic Status and Wealth Index

A composite wealth index is tested in a large number of countries in relation to inequities in household expenditure and income, use of health services, and health outcomes (14). The index is an indicator of the level of wealth that is assumed to be consistent with expenditure and income measures. The index is constructed from data on household ownerships of durable goods (almirah, table, chair, radio, television, watch, bicycle, motorcycle, rickshaw, CNG scooter, sewing machine, and mobile phone) and dwelling characteristics (such as source of drinking-water, sanitation facilities, and construction materials). The principal components analysis of the durables retained one factor and assigned a factor score to each household. The higher the score the higher was the number of household assets, indicating better long-term economic status of the household. The factor score was used in dividing the households into quintiles – from the lowest 20% to the highest 20%. Table 2.5.1 shows descriptive statistics and factor loadings of the household assets (including basic amenities and structural materials of the household) in 2007, 2009, and 2011. On the basis of factor loadings, only significant variables at 1% level of significance are retained in the final principal components analysis (15, 16).

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 12

Table 2.5.1. Mean and factor loadings of standardized variables used for constructing asset

score in Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Selected household

Mean Factor

possessions

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

Piped inside dwelling

0.601 0.574 0.680 0.244 0.134 0.278

(Yes=1, No=0)

Sanitation facility

No=0) 0.332 0.104 0.274 0.179 0.220 0.201

0.154 0.181 0.269 0.028 0.131 0.098

Open latrine/bush/field

0.305 0.694 0.446 0.339 0.303 0.292

(Yes=1, No=0) Electricity

0.921 0.960 0.982 0.379 0.323 0.298

Household assets

Almirah/wardrobe (Yes=1,

0.366 0.396 0.589 0.609 0.660 0.671

0.291 0.329 0.364 0.588 0.646 0.595

No=0) 0.299 0.320 0.376 0.636 0.683 0.627

0.156 0.774 0.046 0.285 0.305 0.145

0.489 0.571 0.623 0.661 0.704 0.658

No=0) 0.576 0.498 0.517 0.646 0.654 0.631

0.049 0.024 0.031 0.214 0.117 0.137

No=0) 0.006 0.009 0.121 0.130 0.157 0.117

Rickshaw/Van (Yes=1,

0.058 0.039 0.535 0.039 0.022 0.059

No=0) CNG scooter (Yes=1, No=0)

Sewing machine (Yes=1,

0.051 0.068 0.089 0.307 0.226 0.197

No=0) Mobile phone (Yes=1, No=0)

Main roof material

No=0) 0.062 0.123 0.154 0.323 0.367 0.383

Main wall material

No=0) 0.422 0.594 0.638 0.665 0.610 0.646

Floor material

0.666 0.805 0.837 0.594 0.533 0.576

Household durables of the three surveys are merged together and the principal components analysis is conducted to retain one factor and assign a factor score to each household. Table 2.5.2 shows the percent distribution of households by asset quintiles in the project and the comparison slums over the years. Economic position of slum households improved over the years; it has been more frequent in the project area than in the comparison area. More

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 13

households of the 2007 baseline survey belonged to the poorest quintile than households of

the 2009 midline survey or the 2011 endline survey in the project area. On the other hand,

more households of the 2011 endline survey belonged to the least poor quintile than the

households in the 2007 baseline survey or the 2009 midline survey.

Table 2.5.2. Percent distribution of women by household asset quintiles by area in Dhaka

urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

Asset quintile

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

39.4 16.7 12.0 22.5 24.6 14.2 20.1

23.4 18.2 16.8 19.7 24.8 20.6 19.9

19.0 20.1 20.0 19.9 20.7 22.4 20.2

10.4 19.8 23.7 19.9 16.9 25.1 19.8

7.8 25.1 27.5 18.0 13.1 17.7 20.1

100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

1,256 2,172 2,269 1,227 1,054 1,129 9,107

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 14

CHAPTER 3: CHARACTERISTICS OF SURVEY WOMEN

This chapter describes the demographic and socioeconomic profiles of women interviewed in 2007, 2009, and 2011. These surveys collected basic information on women's age, level of education, marital status, and religion. Information is also collected on women's exposure to mass media, employment status and occupation, type of employment, income and expenditure, NGO involvement, and migration history.

3.1 Background Characteristics of Women

Table 3.1.1 shows the percent distribution by selected background characteristics, of women interviewed in the 2007, 2009, and 2011 surveys. Age distribution of the sampled women of the three surveys in the project and the comparison areas were comparable. Majority of women were aged between 20 and 29 years. In both project and the comparison areas, women were predominantly Muslim (96-99%) in either survey. The rate of the ‘currently married women' was similar in the project and the comparison areas in 2007, 2009, and 2011.

The educational attainment of its population is an important indicator of a society's stock of human capital and its level of socioeconomic development. Education also enhances the ability of individuals to achieve desired demographic and health goals. The percentage of women with no education was the lowest in 2011, followed by 2009 and 2007 in the project area (26, 32, and 51% respectively), and this was not the case in the comparison areas (30, 42, and 37% respectively). As expected, the percentage of women with secondary education (class VI+) was the highest in 2011, followed by 2009, and 2007 in the project area. In the comparison area, the percentage of women with secondary education was comparable in 2007, 2009, and 2011.

Access to mass media: Access to information through the media is essential for updating

knowledge and raising awareness of what is happening around them. The surveys assessed

women's exposure to media by asking if they listened to radio, watched television, or read

newspapers or magazines at least once a week. Among the sampled women, the percentage

of women who read newspapers was higher in 2011 than in 2007 (10% versus 7%) in the

project area but opposite in the comparison area―lower in 2011 than 2007 (5% versus 13%).

Regular exposure to electronic media, i.e. television, was widespread among the women –

watching television project at least once a week was more than 81% in either area in 2007,

2009, and 2011. In comparison to television, women's exposure to radio gradually declined

from 22-24% in 2007 to 4-5% in 2011 in both areas. On inquiry about their current

employment status, fewer women were employed in 2011 compared to 2007 in either area

(17-21% versus 25-26%).

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 15

Table 3.1.1. Percent distribution of women by socio-demographic characteristics in

Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

Women's age (year)

Marital status

Currently married

Divorced, separated, or

1.8 0.8 0.5 1.0 1.2 0.8

Married once or more

Married more than once

Education level (classed passed)

Primary incomplete (class

15.4 13.5 15.4 13.7 15.3 21.9

Primary complete (class

15.3 17.3 18.9 17.8 16.6 19.4

Secondary incomplete

16.2 28.0 31.4 23.6 22.5 25.5

Secondary complete or

2.2 9.2 8.3 7.7 4.1 3.5

Regular exposure to mass media

Reads newspapers 7.2

Listens to radio

Watches television

Currently employed

Total number

3.2 NGO Involvement

Table 3.2.1 presents the percent distribution of women by membership of selected non-

government organizations (NGOs) in Dhaka urban slums in 2007, 2009, and 2011. The

percentage of women's involvement with NGOs was lower (9-13% in 2009 and 2011

compared to 23% in 2007) in the project and the comparison areas. A few women (<1%)

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 16

were involved in more than one NGO in 2009 and 2011 opposed to 2-3% in 2007. ASA (Assistance for Social Advancement) was the leading NGO in the project and comparison areas in 2009 and 2011 while BRAC was leading in the project area in 2007. Involvement with small localized NGOs was common in both the areas.

Table 3.2.1. Percent distribution of women by NGO involvement and membership in

Dhaka urban slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Project area

Comparison area

NGO involvement

Currently involved with NGO

Number of NGOs involved with

Has membership of1

100.0 100.0 100.0

100.0 100.0 100.0

1,256 2,172 2,269

1,227 1,054 1,129

1Among the women who are involved with NGO activities

3.3 Income/Employment Activities

In the 2007, 2009 and 2011 surveys, women (who are employed on the survey date) are asked

a number of questions regarding type and nature of their employment status, and the results

are presented in Table 3.3.1. A major shift was marked in type of employment, with decrease

in percentage of domestic work, daily labour and trading and an increase in the percentage of

service in the project area over the years. Such a shift was not evident in the comparison area.

The most common type of employment was the service in both areas in all years, followed by

domestic work in the project area and skilled labour in the comparison area. The other

common types of employment were daily labour, followed by trading, and making handicraft.

Most of the employed women work round the year in either area. One-third of the women

report sole control over the spending of their income and more than half report joint-control

of husband and wife over the spending of wife's income. There was an increase in percentage

of sole control and a decrease in joint control of wife's income over the years.

Impact Evaluation Surveys in Dhaka Urban Slums 2007, 2009 and 2011 17

Table 3.3.1. Percent distribution of women by employment characteristics in Dhaka urban

slums, 2007, 2009, and 2011

Employment

Project area

Comparison area

2007 2009 2011 2007 2009 2011

Type of employment

Construction work

Nature of employment

Control over spending income1

Respondent and husband

64.3 58.1 57.8 61.2 56.5 45.3

jointly Respondent and someone

1.3 0.8 4.5 5.4 2.5 1.7

else jointly

Total %

Total number

1Applicable for cash incomes only

3.4 Migration History

Traditionally, in-migration, particularly from rural areas, has been the most important factor in the rapid growth of cities and the development of slums. Poor rural migrants concentrate mainly in the slum areas of cities. Sampled women were asked this question 'How long have you been living continuously in the current place of residence?' Information collected through this question was used in determining the status of a respondent as a migrant or a non-migrant as well as to determine his/her duration of residence at the place of enumeration. Persons who had always stayed at the place where they were enumerated were clearly non-migrants, and those who had not always lived in the place of enumeration were considered to be migrants in the enumeration place.