General guidelines for agitated patients in palliative care

Symptom

Management

Pocket Guides:

DELIRIUM

DYSPNEA

NAUSEA & VOMITING

PAIN

LOSS OF APPETITE

BOWEL CARE

ORAL CARE

August 2010/July 2012

Table of Contents

ESAS…………………………….………….97 Click on hyperlink to go to specific symptom.

Delirium

Considerations ……………………….…… 1

Assessment ………………………………… 2

Diagnosis ……………………………………. 3

Non-Pharmacological treatment 3

Pharmacological treatment …….… 5

Mild Delirium………………………….…. 6

Moderate Delirium………………….… 6

Severe Delirium ……………………….… 7

Adverse Effects …………………………. 7

Selected References …………………. 9

The underlying etiology needs to be

identified in order to intervene.

Delirium may interfere with the patient‟s

ability to report other symptom experiences.

Provide explanation and reassure the

family that the symptoms of delirium will fluctuate, are caused by the illness, are not within the patient‟s control, and the patient is not going „insane‟.

Some hallucinations, nightmares, and

misperceptions may reflect unresolved fears, anxiety or spiritual passage.

Include the family in decision making,

emphasizing the shared goals of care; support caregivers.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium 1

Correct reversible factors – infection,

constipation, pain, withdrawal, drug toxicity.

Review medications; consider opioid

rotation to reverse opioid neurotoxicity; discontinue unnecessary drugs or prolong dosing interval for necessary drugs. Anticipate the need to change treatment

options if agitation develops, particularly in cases where patient, family and staff safety may become threatened.

Misinterpreting symptoms of agitation/

restlessness, moaning and/or grimacing as poorly controlled pain, with subsequent administration of more opioids, can potentially aggravate the symptom and cause opioid neurotoxicity.

Assessment

Ongoing comprehensive assessment is the

foundation of effective management of delirium and restlessness including interview, physical assessment, medication review, medical and surgical review, psychosocial review, review of physical environment and appropriate diagnostics.

Delirium may interfere with optimal pain

and symptom expression (self-reporting), assessment and management.

In situations where a patient is not able to

complete an assessment by self reporting, then the health professional and/or the caregiver may act as a surrogate.

2 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium

Diagnosis

Identifying the underlying etiology of the

delirium or restlessness is essential in determining the interventions required.

The causes of delirium are usually multi-

factorial (See table below, adapted from Capital Health).

Determining the underlying etiology,

education/reassuring the patient/family and treating the symptoms should occur simultaneously.

D Drugs, drugs, drugs, dehydration, depression

Electrolyte, endocrine dysfunction (thyroid, adrenal),

E ETOH (alcohol) and/or drug use, abuse or

L Liver failure

I Infection (urinary tract infection, pneumonia, sepsis)

R Respiratory problems (hypoxia), retention of urine or

stool (constipation)

I Increased intracranial pressure;

U Uremia (renal failure), under treated pain

Metabolic disease, metastasis to brain, medication

M errors/omissions, malnutrition (thiamine, folate or

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Report hallucinations that become

Instruct the family to provide gentle,

repeated reassurance and avoid arguing with the patient.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium 3

Watch for the "sun downing" effect

(nocturnal confusion) , as it may be the first symptom of early delirium.

Provide a calm, quiet environment and

help the patient reorient to time, place and person (visible clock, calendar, well known or familiar objects).

Presence of a well known family

member is preferred.

Provide a well lit, quiet environment.

Provide night light.

To prevent over-stimulation, keep

visitors to a minimum, and minimize staff changes and room changes.

Correct reversible factors – dehydration,

nutrition, alteration in visual or auditory acuity (provide aids), sleep deprivation.

Avoid the use of physical restraints and

other impediments to ambulation. Avoid catheterization unless urinary retention is present.

Encourage activity if patient is

physically able.

When mildly restless provide

observation and relaxation techniques (massage, tub baths, gentle music) as applicable.

Encourage the family to be present in a

4 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium

Pharmacological Treatment

Review medications; consider opioid rotation

to reverse opioid neurotoxicity

Consider psychotropic drugs for patients

developing "sun downing" effect (confusion in the evening).

Anticipate the need to change treatment

options if agitation develops – particularly in cases where patient, family and staff safety may become threatened.

Benzodiazepines may paradoxically excite

some patients and should be avoided unless the source of delirium is alcohol or sedative drug withdrawal, or when severe agitation is not controlled by the neuroleptic.

If patient has known or suspected brain

metastases a trial of corticosteroids is worthwhile. o Dexamethasone 16 - 32 mg po daily in the

morning may be used (Suggestion is based on expert opinion and doses may vary from region to region).

Misinterpreting symptoms of agitation/

restlessness, moaning and/or grimacing as poorly controlled pain, with subsequent administration of more opioids, can potentially aggravate the symptom and cause opioid neurotoxicity.

Titrate starting dose to optimal effect.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium 5

Mild Delirium

Orient patient as per non-pharmacological

recommendations.

Pharmacological

Haloperidol is the gold standard for

management of delirium.

If titration with haloperidol is not effective

consider using methotrimeprazine.

Haloperidol 0.5-1 mg po / subcut bid-tid Alternate agents:

o Risperidone 0.5-1 mg po bid o Olanzapine 2.5–15 mg po daily o Quetiapine fumarate 50-100 mg po bid o Methotrimeprazine 5-12.5 mg po OR

6.25-12.5 mg subcut q4-6h prn

o Chlorpromazine 25-50 mg po q4-6h prn

Moderate Delirium

Pharmacological

Haloperidol 0.5-2 mg subcut q1h prn until

episode under control; may require a starting dose of 5 mg subcut

Alternate agents:

o Risperidone 0.5-1 mg po bid o Olanzapine 2.5-15 mg po daily o Quetiapine fumarate 50-100 mg po bid

Benzodiazepines may paradoxically excite some

patients and should be avoided unless the source

6 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium

of delirium is alcohol or sedative drug withdrawal, or when severe agitation is not controlled by the neuroleptic

Severe Delirium

Titrate starting dose(s) to optimal effect.

If agitation is refractory to high doses of

neuroleptics, (as outlined in moderate delirium) consider adding lorazepam 0.5-2 mg subcut q4-6h prn or midazolam 2.5-5 mg subcut q1-2h prn in conjunction with the neuroleptic.

Alternate agents to consider:

o Methotrimeprazine 12.5–25 mg subcut

q8-12h and q1h prn OR

o Chlorpromazine 25-50 mg po/subcut

If above not effective consider:

o Haloperidol 10 mg subcut. Typically,

in palliative care the maximum dose of haloperidol is 20 mg/day OR

o Methotrimeprazine 25-50 mg subcut

q6-8h and q1h prn.

Adverse Effects of Medications

Used to Treat Delirium

Extrapyramidal side effects (EPS) are

common adverse events of neuroleptics, with the newer atypical neuroleptics having a lower risk of EPS than the older typical neuroleptics.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium 7

Potentially all dopamine antagonists can

cause EPS, to varying degrees, due to the D2 central antagonist actions.

Manifestations of EPS are usually dose

dependent. Extrapyramidal side effects may include: acute dystonia, akathisia, and Parkinson-like signs/symptoms.

Akathisia and acute dystonias tend to

resolve with discontinuation of the offending drug.

For the treatment of mild cases one should

consider discontinuation of the drug or switching to a less antidopaminergic agent if possible.

If pharmacologic management is needed,

then consider benztropine (1st line) 1-2 mg po/subcut bid (or 2mg IM/IV for acute dystonic reactions). Alternative medications include biperiden 2 mg po bid or diphenhydramine 25-50 mg po/subcut bid to qid (or 25-50 mg IV/IM for acute dystonia).

8 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium

Selected References

1) Fraser Health. Hospice Palliative Care Program

Symptom Guidelines: Delirium/Restlessness. Fraser Health Website, 2006. Accessed: August 2008. Available from:

2) Common Questions by Capital Health, Regional

Palliative Care Program Edmonton, 3rd Edition, 2006, Pg. 60.

3) Adapted with permission from the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Palliative Care. V.2.2011. Website:

For full references and more information please refer to

Disclaimer:

Care has been taken by Cancer Care Ontario‟s

Symptom Management Group in the preparation of the

information contained in this pocket guide.

Nonetheless, any person seeking to apply or consult the

pocket guide is expected to use independent clinical judgment

and skills in the context of individual clinical circumstances

or seek out the supervision of a qualified specialist clinician.

CCO makes no representation or warranties of any kind

whatsoever regarding their content or use or application and

disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium 9

10 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Delirium

Non-Pharmacological treatment… 12

Pharmacological treatment …….……. 13

Mild Dyspnea …………………….……………. 13

Moderate Dyspnea …………….………… 15

Severe Dyspnea ……………………….……. 17

Oxygen Cost Diagram………………………. 22

Selected References ………………………. 23

Because dyspnea is subjective, the patient‟s

self report of symptoms should be acknowledged and accepted.

Identify and treat common exacerbating

medical conditions underlying dyspnea or shortness of breath, e.g. COPD, CHF, pneumonia (link to table in guide).

Evaluate impact of anxiety and fear on

dyspnea and treat appropriately.

Use Edmonton Symptom Assessment

System (ESAS) and Oxygen Cost

Diagram (OCD) (See OCD) to measure

outcome.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea 11

Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Ambient air flow can be achieved by

opening a window, using a fan, or administering air through nasal prongs.

Cool temperatures can be applied to the

brow or upper cheek bones by applying a cool cloth or opening a window to let cooler air in.

A program of cognitive behavioural

interventions involving the following 6

interventions for a time period of 3 to 8

weeks is recommended:

1) Assessment of breathlessness – what

improves and what worsens it

2) Provision of information and support

for patients and families in the management of breathlessness

3) Exploration of the significance of

breathlessness with patients, their disease, and their future

4) Instruction on breathing control,

relaxation and distraction techniques and breathing exercises

5) Goal setting to enhance breathing and

relaxation techniques as well as to enhance function, enable participation in social activities and develop coping skills

6) Identification of early signs of

problems that need medical or pharmacotherapy intervention

These suggestions should be taught as preventative strategies, when patients are not dyspneic, and regular practice should be encouraged.

12 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea

Pharmacological Treatments

Mild Dyspnea ESAS 1 to 3

Supplemental oxygen is recommended for

hypoxic patients experiencing dyspnea.

Supplemental oxygen is not recommended

for non-hypoxic, dyspneic patients.

Non-hypoxic Patients (>90% O2 saturation) 1

For patients with PPS 100% - 10%:

Use a fan or humidified ambient air via nasal

prongs (as per patient preference and

availability). This is not covered by the Ontario

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

(MOHLTC)

If effective and tolerated, then utilize one or

If not effective or not tolerated, consider a

trial of humidified, supplemental oxygen via nasal prongs – assess benefits over a few days and discontinue if no benefit reported for dyspnea (covered by MOHLTC on the Home Oxygen program for up to 3 months if the "palliative care" indication is used).

1 ≤88% oxygen saturation at rest or on exertion is the

threshold for MOHLTC approval of funding for home

oxygen for palliative care patients beyond 3 months; for

some patients ≤90% oxygen saturation may be a more

appropriate threshold for introducing home oxygen therapy.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea 13

Hypoxic Patients (≤90% O2 saturation at rest

or on exertion)

For Patients with PPS 100% - 10%:

Use humidified, supplemental oxygen via nasal

prongs, continuously or as-needed, at flow rates

between 1 and 7 litres per minute, aiming for

oxygen saturations over 90% or improvement in

dyspnea at tolerated flow rates.

Continue this therapy if it is effective at

improving dyspnea and is tolerated.

If dyspnea and low oxygen saturation persist despite maximum-tolerated flow of humidified, oxygen by nasal prongs, consider offering a trial of supplemental oxygen by oxymizer (nasal cannulae with reservoir), ventimask or non-rebreathing mask to deliver a more predictable fraction of inspired oxygen to the lungs. If this is not tolerated, the patient can return to the best-tolerated flow of humidified oxygen by nasal prongs or discontinue supplemental oxygen altogether.

Systemic opioids, by the oral or

parenteral routes, can be used to manage

dyspnea in advanced cancer patients.

For patients with PPS 100-10%: Other pharmacological treatments are not generally needed for patients with mild dyspnea, regardless of their PPS; however, systemic opioids (oral or parenteral) may be considered if non-pharmacological approaches result in inadequate relief of dyspnea. Consider systemic opioids for mild,

continuous dyspnea, not for dyspnea that is mild and intermittent (eg. on exertion) since

14 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea

any benefit is limited by the time to onset of effect.

If systemic opioids are considered, weigh

their potential risks and benefits and reassess the severity of the dyspnea and the effect the dyspnea has on the patient‟s function.

If the patient is already taking a systemic

opioid for another indication, such as pain o titrate the dose of the same opioid, if it is

well-tolerated, to improve the dyspnea

o switch to an alternate opioid, if the

current opioid is not tolerated, and titrate it to improve the dyspnea

If the patient is opioid naïve, introduce an

opioid to treat the dyspnea.

Properly titrated, systemic opioids do not

produce respiratory depression.

Moderate Dyspnea ESAS 4 to 6

For Patients with PPS 100% - 10%:

Non Opioids

May use benzodiazepines for anxiety. There is no evidence for the use of systemic

corticosteroids

Systemic Opioids

For opioid-naïve patients:

Morphine (or equivalent dose of alternate

immediate-release opioid) 5mg po q4h

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea 15

regularly and 2.5mg po q2h PRN for breakthrough dyspnea

If the oral route is not available or reliable,

morphine 3 mg subcut q4h regularly and 1.5

mg subcut q1h PRN for breakthrough

dyspnea.

For patients already taking systemic

opioids:

Increase the patient‟s regular dose by 25%,

guided by the total breakthrough doses used in the previous 24 hours

The breakthrough dose is 10% of the total

24-hour regular opioid dose, using the same opioid by the same route.

o oral breakthrough doses q2 hrs as needed o subcutaneous breakthrough doses q1hr as

needed, due to more rapid peak effect.

Do not use nebulized opioids, nebulized

furosemide, nebulized lidocaine or benzodiazepines.

For Patients with PPS 100% - 20%

If patient has or may have COPD, consider a

5-day trial of a corticosteroid

o Dexamethasone 8 mg/day po or subcut or

o Prednisone 50 mg/day po o Discontinue corticosteroid if there is no

obvious benefit after 5 days

If the patient does not have COPD, but has

known or suspected lung involvement by the cancer, weigh the risks before commencing a 5-day trial

o Other potential benefits, such as for

appetite stimulation or pain management, may justify a 5-day trial of a corticosteroid

16 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea

Do not start prophylactic gastric mucosal

protection therapy during a 5-day trial of a corticosteroid, but consider such therapy if the corticosteroid is continued past the trial

Prochlorperazine is not recommended as a

therapy for managing dyspnea.

No comparative trials are available to support

or refute the use of other phenothiazines, such as chlorpromazine and methotrimeprazine.

For Patients with PPS 30% - 10%:

Consider a trial of chlorpromazine or

methotrimeprazine, if dyspnea persists despite other therapies

o Methotrimeprazine 2.5-10 mg po or subcut

q6-8h regularly or as needed

o Chlorpromazine 7.5-25 mg po q6-8h

regularly or as needed

Anxiety, nausea or agitation, may justify a

trial of chlorpromazine or methotrimeprazine

Severe Dyspnea ESAS 7 to 10

For Patients with PPS 100% - 10%:

Systemic Opioids

For opioid-naïve patients:

Give a subcut bolus of morphine 2.5 mg (or

an equivalent dose of an alternate opioid). o If tolerated, repeat dose every 30 minutes if

o Consider doubling dose if 2 doses fail to

produce an adequate reduction in dyspnea and are tolerated

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea 17

o Monitor the patient‟s respiratory rate

closely, since the time to peak effect of a sc dose of morphine may be longer than 30 minutes

If intravenous access is available, consider

giving an IV bolus of morphine 2.5 mg (or an equivalent dose of an alternate opioid) to achieve a more rapid effect.

o If tolerated, repeat dose every 30 minutes if

o Consider doubling dose if 2 doses fail to

produce an adequate reduction in dyspnea and are tolerated

o Monitor the patient‟s respiratory rate

closely, since IV boluses of morphine result in faster and higher peak effects.

Start a regular dose of an immediate-release

opioid, guided by the bolus doses used

o For the breakthrough opioid dose, consider

using the subcut route initially for severe dyspnea until the symptom comes under control.

For patients already taking systemic opioids:

Follow the same suggestions as above for

opioid naïve patients, with the following changes.

o Give a subcut bolus of the patient‟s current

opioid using a dose equal to 10% of the regular, 24-hour, parenteral-dose-equivalent of the patient‟s current opioid (a parenteral dose is equivalent to half the oral dose)

o Consider giving an IV bolus of the

patient‟s current opioid, using a dose equal to 10% of the regular, 24-hour, parenteral-

18 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea

dose-equivalent of the patient‟s current opioid

o Increase the regular opioid dose by 25%,

guided by the bolus doses used

Phenothiazines

Consider a trial of chlorpromazine or

methotrimeprazine, if severe dyspnea persists despite other therapies.

Methotrimeprazine 2.5-10 mg po or subcut

q6-8h regularly or as needed

Chlorpromazine 7.5-25 mg po or IV q6-8h

regularly or as needed

Consider benzodiazepine for co-existing

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea 19

Titration Guide

General principles:

1.

Calculate the total opioid dose taken by the patient in

24 h (regular q4h dose x 6 PLUS the total number of

breakthrough doses given x breakthrough dose).

Divide this 24 h total by 6 for the equivalent q4h dose.

Divide the newly calculated q4h dose by 2 for the breakthrough dose.

Use clinical judgment regarding symptom control as to whether to round up or down the obtained result (both breakthrough and regular dosing). Remember to consider available doses (in the case of PO medications especially).

If the patient is very symptomatic, a review of how many breakthrough doses have been given in the past few hours might be more representative of his/her needs.

Example:

A patient is ordered morphine 20 mg q4h PO and 10 mg

PO q2h PRN, and has taken 3 breakthrough doses in the

past 24 h.

1.

Add up the amount of morphine taken in the past 24 h:

6 x 20 mg of regular dosing, plus 3 x 10 mg PRN doses equals a total of 150 mg morphine in 24 h

Divide this total by 6 to obtain the new q4h dose:

150 divided by 6 = 25 mg q4h

Divide the newly calculated q4h dose by 2 to obtain the new breakthrough dose: 25 mg divided by 2 = 12.5 mg q1 - 2h PRN

If this dose provided reasonable symptom control, then order 25 mg PO q4h, with 12.5 mg PO q1 - 2h PRN. (It would also be reasonable to order 10 mg or 15 mg PO q2h for breakthrough.)

20 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea

Conversion Guide

(To convert from long-acting preparations to short-

acting preparations)

General principles in converting from sustained

release to immediate release preparations (for the

same drug):

1. Add up the total amount of opioid used in the past

24 h, including breakthrough dosing.

2. Divide this total by 6 to obtain equivalent q4h

3. Divide the q4h dose by 2 to obtain breakthrough

4. Use clinical judgment to adjust this dose up or

down depending on symptom control.

5. Consider available tablet sizes when calculating

Example:

A patient is ordered a sustained release morphine

preparation at a dose of 60 mg PO q12h, with 20 mg

PO q4h for breakthrough, and has taken 4

breakthrough doses in 24 h.

1. Add up the amount of opioid taken in 24 h: 2 x 60

mg of sustained release morphine plus 4 x 20 mg of breakthrough is 200 mg of morphine in 24 h

2. Divide this total by 6 to obtain the equivalent q4h

dosing: 200 divided by 6 is approximately 33 mg PO q4h

3. Divide this q4h dose by 2 for the breakthrough

dose 33 mg divided by 2 is 16.5 mg

If the patient had reasonable symptom control with the previous regimen, then a reasonable order would be: 30 mg PO q4h and 15 mg q1 - 2h PO PRN

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea 21

Oxygen Cost Diagram (OCD)

The Oxygen Cost Diagram is a 100 mm vertical lines along

which every day activities are placed which correspond to

different activity levels and oxygen cost. The activities

range from "brisk walking uphill" to "sleeping". Patients are

asked to mark the activity that will make them breathless.

McGavin et al found that the patient‟s ratings of their

breathlessness with this scale were correlated r = 0.68

(p<0.001) with the 12 minute walking test. (McGavin et al,

1978) Others have found that the OCD correlated

significantly with lung function and respiratory muscle

strength. (Mahler et al, 1988)

EQUIANALGESIC CONVERSION TABLE

12:1 (PO codeine

oxycodone to PO morphine)

hydromorphone to PO morphine)

22 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea

Selected References

1) Fraser Health (2009) „Hospice Palliative Care

Program Symptom Guidelines: Dyspnea‟ Fraser Health Website [Internet]. Available from: (Accessed: 23 July 2009).

2) Oncology Nursing Society (2008) „Putting

Evidence Into Practice: Evidence-Based Interventions for Cancer-Related Dyspnea‟ Oncology Nursing Society Website [Internet]. Available from:

3) Viola, R., Kiteley, C., Lloyd, N., Mackay, J. A.,

Wilson, J., Wong, R. and the Supportive Care Guidelines Group (2006) „The Management of Dyspnea in Cancer Patients: A Clinical Practice Guideline‟ Program in Evidence Based Care Series 13-5, Cancer Care Ontario.

For full references and more information please refer t

Disclaimer:

Care has been taken by Cancer Care Ontario‟s

Symptom Management Group in the preparation of the

information contained in this pocket guide.

Nonetheless, any person seeking to apply or consult the

pocket guide is expected to use independent clinical judgment

and skills in the context of individual clinical circumstances

or seek out the supervision of a qualified specialist clinician.

CCO makes no representation or warranties of any kind

whatsoever regarding their content or use or application and

disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Dyspnea 23

Nausea & Vomiting

Assessment ………………………………… 25

Diagnosis ……………………………………. 25

Non-Pharmacological treatment. 26

Pharmacological Treatment ……… 28

Selected References …………………. 33

Assessment

Comprehensive assessment includes: interview, physical assessment, nutrition assessment, medication review, medical and surgical review, psychosocial and physical environment review and appropriate diagnostics.

Diagnosis

Nausea and vomiting is common and

has multiple etiologies, several of which

may be present at the same time, hence

identifying the underlying causes is

essential.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting 25

Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Providing information and education is

recommended as it is fundamental to

enhance the patient and family's ability

to cope.

Consult with the inter-professional team

members (e.g., social worker, spiritual practitioner, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, counselor for psychosocial care and anxiety reduction).

Explain to the patient/family what is understood about the multiple triggers of nausea and/or vomiting and that it may take a number of strategies to make a difference

Consult with a Clinical Dietitian and have

them provide dietary/nutritional advice

Limit spicy, fatty and excessively salty or

sweet foods, foods with strong odours and foods not well tolerated.

Use small, frequent, bland meals and

snacks throughout the day. Suggest small amounts of food every few hours. (Hunger can make feelings of nausea stronger).

Hard candies, such as peppermints or

lemon drops may be helpful.

Sip water and other fluids (fruit juice, flat

pop, sports drinks, broth and herbal teas such as ginger tea) and suck on ice chips, popsicles or frozen fruit. It is important to try and drink fluids throughout the day even when not feeling thirsty.

26 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting

Limit the use of caffeine, including colas

and other caffeinated soft drinks, such as coffee drinks, and tea (both hot and cold).

Reduce meal size when gastric distension is

Ingest liquids and solids separately. It is

often helpful to drink fluids after and/or in between meals.

Consume food/liquids cold or at room

temperature to decrease odours.

Sit upright or recline with head elevated for

30-60 minutes after meals.

If vomiting, limit all food and drink until

vomiting stops; wait for 30-60 minutes after vomiting, then initiate sips of clear fluid.

When clear fluids are tolerated, add dry

starchy foods (crackers, dry toast, dry cereal, pretzels)

When starchy foods are tolerated, increase

diet to include protein rich foods (eggs, chicken, fish) and lastly incorporate dairy products into the diet.

Environmental modification

(where possible)

Eliminate strong smells and sights.

Optimize oral hygiene, especially after episodes of vomiting. Rinse with ½ tsp baking soda, ½ tsp salt in 2 cups water.

Try rinsing mouth before eating to remove thick oral mucus and help clean and moisten mouth.

Wear loose clothing.

If possible try to create a peaceful eating place with a relaxed, calm atmosphere. A well ventilated room may also be helpful.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting 27

Complementary Therapies

Acupuncture or acupressure points. Visualization, hypnosis, distraction.

Pharmacological Treatments

Selection of antiemetics should be based on the

most likely etiology of nausea and vomiting and site of action of medication.

Any unnecessary medications that may be

contributing to nausea and vomiting should be discontinued.

Constipation may be a factor contributing to

nausea and vomiting and requires treatment.

It is necessary to rule out bowel obstruction and

if present, appropriate treatment should be undertaken.

Choosing an antiemetic

Metoclopramide is recommended as the drug of

first choice to control chronic nausea/vomiting in patients with advanced cancer.

Titrate metoclopramide to maximum benefit and

tolerance. If not effective add/switch to another dopamine antagonist (e.g. haloperidol).

Domperidone may be substituted for patients

who can swallow medications and who have difficulties with extrapyramidal reactions.

Titrate antiemetics to their full dose, unless

patient develops undesirable effects, before adding another drug.

If nausea is not controlled with a specific

antiemetic within 48h, add another antiemetic

28 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting

from another group, but do not stop the initial agent.

Consider combinations but monitor overlapping

toxicities.

Use regular dosing of antiemetics if

experiencing constant nausea and/or vomiting.

For persistent nausea and/or vomiting

antiemetics should be prescribed on a

regular dosing schedule with a breakthrough

dose available.

All medications need to be individually titrated

to the smallest effective dose or until undesirable side effects occur.

Treatment and Management

1. Treat the cause, if possible. 2. Symptomatic management:

Fluid and electrolyte replacement as

Nutritional advice – consider making

patient NPO if obstructed or until emesis has resolved for several hours; if not obstructed, change diet as appropriate, depending on the cause of nausea.

Treat gastrointestinal obstruction

(may need to consider interventions such as nasogastric tube (NGT), venting gastrostomy tube (PEG), stents, ostomies, possible surgical resection).

Pharmacological treatment of

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting 29

Pharmacological Treatment of

Symptoms: Step 1

The choice of antiemetic depends on the cause and the receptors and neurotransmitters involved:

For delayed gastric emptying or

abdominal causes (excluding bowel

obstruction, see above):

o Metoclopramide 5-20 mg po/subcut/IV

q6h (or tid AC meals plus qhs); may be used q4h if needed; 40-100 mg/24 h subcut/IV continuous infusion.

o Alternative (if metoclopramide is not

well tolerated): domperidone 10mg TID to QID (The risk of serious abnormal heart rhythms or sudden death (cardiac arrest) may be higher in patients taking domperidone at doses greater than 30mg a day or in patients who are more than 60 years old).

For patients treated with palliative

o For symptoms that occur within 24

hours of administration of radiotherapy: Ondansetron 8 mg po/subcut/IV q8 – 24h; Granisetron 1 mg po q12h or 1 mg IV once daily

o For anticipatory nausea or vomiting:

lorazepam 1-2 mg po/sl/IV/subcut

o The above agents are also best given

prior to radiation for optimal effect.

For opioid-induced nausea:

o Metoclopramide 10-20 mg

po/subcut/IV q6h

30 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting

o Alternative: haloperidol 0.5-2.5 mg

For other chemical/metabolic causes:

o Haloperidol 0.5-2.5 mg po/subcut q12h o Alternative: metoclopramide 10-20 mg

po/subcut/IV q6h

For brain metastases:

o Dexamethasone 4-8 mg po/subcut/IV bid (0800

and 1300 h); for brain metastases that do not respond to dexamethasone or for leptomeningeal carcinomatosis:

o Haloperidol 1-2 mg po/subcut q12h

For vestibular causes:

o Scopolamine (transdermal patch) one or two 1.5

o Alternate: Dimenhydrinate 25-50 mg po/

If psychogenic factors play a role:

o Oxazepam 10 mg po tid or lorazepam 1-2 mg

po/sl/subcut/IV tid

o Psychological techniques (particularly for

chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting)

Pharmacological Treatment of Symptoms:

A combination of different antiemetics is required in approximately 30% of cases. Combination therapy is only beneficial if different neurotransmitters are targeted.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting 31

If the response to monotherapy is inadequate, the following combinations may be considered:

Metoclopramide po/subcut/IV +

dexamethasone po/subcut/IV.

Haloperidol po/subcut + dexamethasone

Pharmacological Treatment of Symptoms:

If dexamethasone combined with either metoclopramide or haloperidol yields insufficient results, the following approaches may be considered:

Serotonin (5HT3) antagonists (ondansetron

4 - 8 mg po/subcut/IV q8-12h; granisetron 1 mg po q12h/1mg IV once daily; or dolasetron 100 mg po/IV once daily); in principle, combine with dexamethasone 4 mg po/subcut/IV once daily. Disadvantages of the serotonin antagonists: high costs; side effects include constipation, headaches.

Methotrimeprazine monotherapy using a

starting dose of 5 – 10 mg po q8h PRN or 6.25-12.5 mg subcut q8h PRN. Increase as needed to maximum of 25 mg per dose.

Olanzapine monotherapy 2.5 – 5 mg

po/sl/subcut once daily or bid.

Diphenhydramine may be used for the treatment of akathesias secondary to increased doses of metoclopramide.

32 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting

Selected References

1) Cancer Care Nova Scotia. Guidelines for the

Management of Nausea and Vomiting In Cancer Patients, Jan 2004.

2) Fraser Health. Hospice Palliative Care Program

Symptom Guidelines. Fraser Health, 2006.

3) Editorial Board Palliative Care: Practice

Guidelines. Nausea and vomiting. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Association of Comprehensive Cancer Centres (ACCC), National Guideline Clearinghouse, 2006.

4) Adapted with permission from the National

Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Palliative Care. V.2.2011. Website:

For full references and more information please refer to

Disclaimer:

Care has been taken by Cancer Care Ontario‟s

Symptom Management Group in the preparation of the

information contained in this pocket guide.

Nonetheless, any person seeking to apply or consult the

pocket guide is expected to use independent clinical judgment

and skills in the context of individual clinical circumstances

or seek out the supervision of a qualified specialist clinician.

CCO makes no representation or warranties of any kind

whatsoever regarding their content or use or application and

disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Nausea & Vomiting 33

Assessment ……………………………………… 35

Non-Pharmacological Treatment …. 37

Pharmacological Treatment …………. 38

Mild Pain ……………….………………………. 41

Moderate Pain ………………………………. 42

Severe Pain ……………….………………… 44

Severe Pain Crisis ………………………… 45

Conversion Ratios….……………………… 46

Selected References …….……………… 51

Assessment

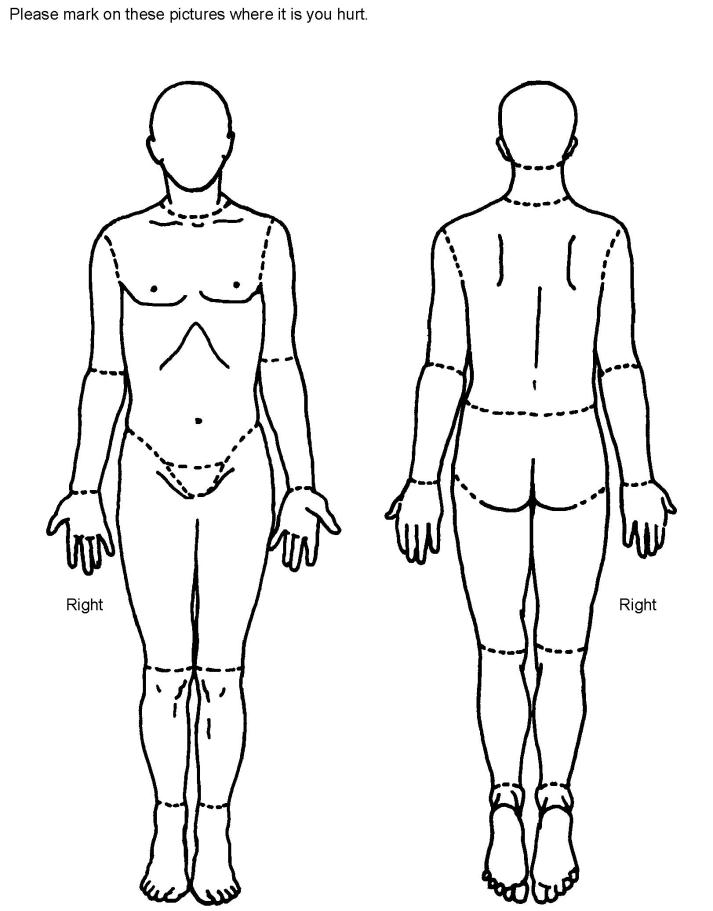

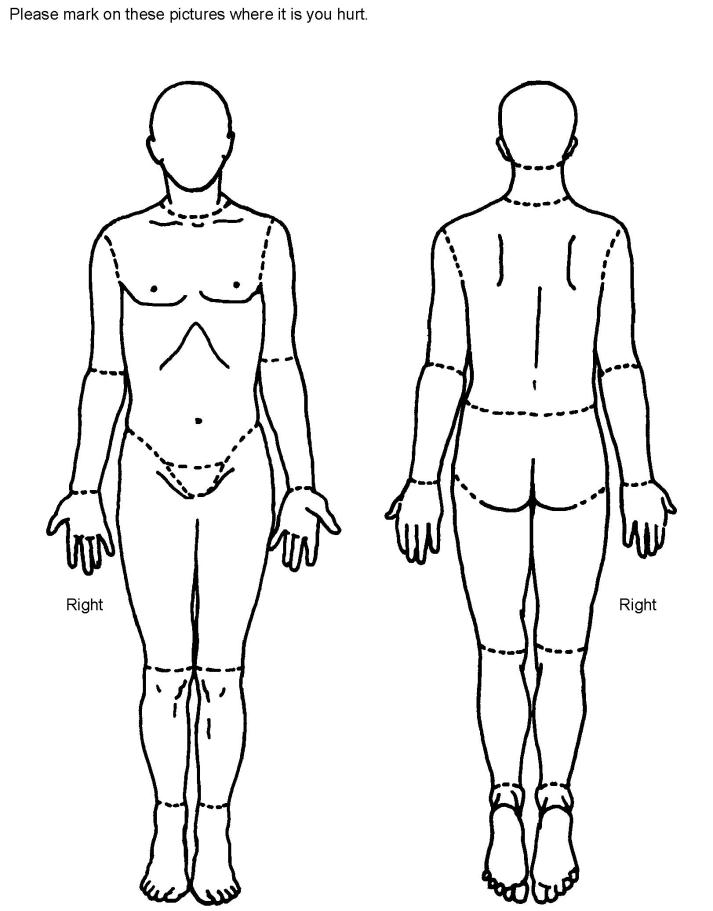

Prior to treatment an accurate assessment

should be done to determine the cause(s), type(s) and severity of pain and its impact.

A comprehensive assessment of pain

should consider the following domains:

o physical effects/manifestations of pain o functional effects (interference with

activities of daily living)

o spiritual aspects o psychosocial factors (level of anxiety,

mood) cultural influences, fears, effects on interpersonal relationships, factors affecting pain tolerance.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 35

Self assessment pain scales should be used

by patients with no cognitive impairment.

Observational pain rating scales should

be used in patients who cannot complete a self assessment scale.

The frequency of the review depends

upon the severity of the pain and associated distress.

General Principles of Cancer Pain

Assessment

1. Perform an adequate pain history. 2. Use tools valid for the patient‟s age

and cognitive abilities, with additional attention to the language needs of the patient (e.g., Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), Palliative Performance Scale (PPS)).

3. Record medications currently taken as

well as those used in the past, including efficacy and any adverse effect.

4. Classify the pain – nociceptive,

neuropathic or mixed?

5. Consider common cancer pain

syndromes while conducting the history and physical examination.

6. Assess for functional impairment and

the need for safety measures.

7. Incorporate a psychosocial evaluation

into the assessment, including determination of the patient‟s/family‟s goals of care

8. Use a pain diary to track the

effectiveness of therapies and evaluate changes in pain.

36 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

9. Review current diagnostic tests for clues

to the origin of the pain. Order a diagnostic test (e.g., MRI, CT, laboratory testing) when warranted for new pain or increasing pain, and only if it will contribute to the treatment plan.

10. Evaluate for the presence of other

symptoms, as pain is highly correlated with fatigue, constipation, mood disturbances, and other symptoms.

11. Assess for risk if opioids are being

Non-Pharmacological Treatment

Radiation Therapy

All patients with pain from bone

metastases which is proving difficult to control by pharmacological means should be referred to a radiation oncologist for consideration of external beam radiotherapy

Vertebroplasty

Vertebroplasty or percutaneous

cementoplasty should be considered in patients with pharmacologically difficult to control bone pain from malignant vertebral collapse or pelvic metastases.

Surgery

Removal of tumours or stabilization of

bones may remove localized pain.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 37

Anesthetic Interventions

Interventions such as coeliac plexus

block and neuraxial opioids should be considered to improve pain control and quality of life in patients with difficult to control cancer pain.

Other Therapies

Consider role for physiotherapy or

occupational therapy

Complementary therapies (e.g. massage,

aromatherapy, music therapy, acupuncture, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, reflexology, Reiki, hypnotherapy) may be considered.

Psycho-social-spiritual interventions

Psycho-social-spiritual interventions

(patient education, counseling, recreational activities, relaxation therapy imagery, social interaction, spiritual counseling) should be considered.

Pharmacological Treatment

General Principles in Using

Adjuvants

The type and cause of the pain will influence

the choice of adjuvant analgesic (e.g. nociceptive, neuropathic, bone metastases).

The choice of antidepressant or

anticonvulsant should be based on concomitant disease, drug therapy and drug side effects and interactions.

38 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

Patients with neuropathic pain should be

given either a tricyclic antidepressant (eg amitriptyline, desipramine, nortriptyline or imipramine) or an anticonvulsant (eg gabapentin or pregabalin) with careful monitoring for adverse effects.

Cannabinoids may have a role in refractory

pain, particularly refractory neuropathic pain.

General Principles in Using Opioids

Educate the patient and/or family about the use of opioids and the expected outcomes.

Anticipate adverse effects like sedation and educate patients about the fact that they will quickly tolerate most adverse effects except for constipation.

In opioid-naïve patients and the frail

elderly, start low and go slow with

titration. Transdermal fentanyl is not

recommended in opioid-naïve patients.

In patients already on opioids, titrate them fairly quickly to the point where they are getting adequate pain control without intolerable adverse effects.

Immediate release or sustained release products can both be used for titration and maintenance.

Give opioids regularly, around the clock for constant pain, not „as required‟.

Always prescribe breakthrough doses.

Prevent adverse effects e.g., for constipation prescribe laxatives right from the initiation of therapy and decide on a plan for the management of constipation.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 39

Monitor patients closely as you are titrating opioids.

10. Use universal precautions where a risk for

abuse is identified.

11. Specialist pain or palliative care advice

should be considered for the appropriate choice, dosage and route of opioids in patients with reduced kidney function or in patients with difficult to control pain.

All patients with moderate to severe cancer

pain, regardless of etiology, should receive a trial of opioid analgesia.

In the presence of reduced kidney function

all opioids should be used with caution and at reduced doses and/or frequency.

Fentanyl, methadone and oxycodone are the

safest opioids of choice in patients with chronic kidney disease.

Methadone requires an experienced

Check for significant drug interactions

before prescribing any drug to a patient

on methadone.

When using a transmucosal fentanyl

formulation for breakthrough pain the effective dose should be found by upward titration independent of the regular opioid dose.

For those with stabilized severe pain and on

a stable opioid dose or those with swallowing difficulties or intractable nausea and vomiting, fentanyl transdermal patches may be appropriate.

40 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

Adverse Effects of Opioids

Many opioid-naïve patients will develop

nausea or vomiting when starting opioids, tolerance usually occurs within 5-10 days. Patients commencing an opioid for moderate to severe pain should have access to an antiemetic to be taken if required.

The majority of patients taking opioids will

develop constipation. Little or no tolerance develops. The commonest prophylactic treatment for preventing opioid-induced constipation is a combination of stimulant (senna or bisacodyl)and osmotic laxatives (lactulose or PEG 3350)

Patient Education should include:

Taking routine and breakthrough analgesics,

adverse effect management, non pharmacologic measures that can be used in conjunction with pharmacologic treatment.

Mild Pain ESAS 1 to 3

TREATMENT WITH NON-OPIOIDS

Acetaminophen and NSAIDS

Acetaminophen and NSAIDS including

COX-2 inhibitors should be considered at the lowest effective dose.

The need for ongoing or long term

treatment should be reviewed periodically, if no significant response in one week drugs should be stopped.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 41

Long term use of NSAIDs should require

gastric mucosa protection.

Bisphosphonates

There is insufficient evidence to recommend

bisphosphonates for first line therapy for pain management.

TREATMENT WITH OPIOIDS

For mild to moderate pain, weak opioids

such as codeine or tramadol could be given in combination with a non-opioid analgesic.

If pain is not controlled with these

combinations go to "Moderate Pain" re: initiation and treatment with opioids

Moderate Pain ESAS 4 to 6

TREATMENT WITH OPIOIDS

If the person is opioid naïve:

o Morphine starting dose is usually 5mg

Q4h with 2.5-5mg Q1H PRN for breakthrough pain. For elderly or debilitated patients consider a starting dose of 2.5mg Q4h.

o Hydromorphone starting dose is 1mg

Q4h with 0.5-1mg Q1h PRN for breakthrough pain. For elderly or debilitated patients consider a starting dose of 0.5 mg Q4h.

42 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

o Oxycodone starting dose is 2.5 mg or

one half tablet Q4H with 2.5 mg or one half tablet Q2H PRN for breakthrough. (The lowest dose oxycodone tablets available, either in combination with acetaminophen or alone, contain 5mg of oxycodone, equivalent to 5-10mg of morphine).

If the person is taking an opioid:

o As an immediate release preparation

with q4h dosing, increase the regular and breakthrough doses by 25%.

o As a sustained release opioid, increase

this dose by 25%. Change the breakthrough dose to 10% of the regular 24h dose, either q1-2h PRN PO or q30 min PRN subcut.

o Patients with stable pain and analgesic

usage, receiving oral morphine, oxycodone or hydromorphone should have the drug converted to a sustained or controlled release formulation given q12h for ease of administration. The short acting breakthrough dose is usually 10% of the total daily dose.

o The frequency of breakthrough doses

for oral opioids is Q1-2h PRN. After conversion to a long acting preparation, if pain is not well controlled, reassess the patient and consider why multiple breakthrough doses are being used and the effectiveness of the breakthrough doses.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 43

o If indicated after proper assessment,

the daily dose can be titrated by adding 20 to 30% of the breakthrough doses used in the preceding 24 hrs to the daily sustained release formulation.

Make frequent assessments and adjustments to the opioid dose until the pain is better controlled.

Severe Pain ESAS 7 to 10

TREATMENT WITH STRONG OPIOIDS

If the person is opioid naïve: Oral:

Morphine 5-10 mg PO q4h and 5mg PO q1h

PRN OR hydromorphine 1.0-2.0 mg PO q4h

and 1.0 mg PO q1h PRN OR Subcutaneous:

Morphine 2.5 - 5 mg subcut q4h & 2.5 mg

subcut q30min PRN OR hydromorphone 0.5

- 1.0 mg subcut q4h & 0.5 mg subcut

q30min PRN.

If the patient is taking an opioid with q4h

dosing, increase the regular and breakthrough doses by 25%. Change frequency of the breakthrough to q1h PRN if PO and q30min PRN if subcut.

If the patient is taking a sustained release

opioid, increase this dose by 25%. Change the breakthrough dose to 10-15% of the regular 24h dose, either q1h PRN PO or q30 min PRN subcut.

Titrate the dose every 24h to reflect the

previous 24h total dose received

If unmanageable opioid-limiting adverse

effects are present (e.g. nausea, drowsiness,

44 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

myoclonus), consider switching to another opioid and re-titrate or consult palliative care.

For patients with severe uncontrolled pain

consider switching back to an equivalent daily dose of immediate release morphine to allow more rapid titration of dose or switch to a sc preparation/infusion.

Meperidine and pentazocine should

generally not be used in cancer patients with chronic or acute pain.

If there is difficulty getting the pain under

control consider a consultation to palliative care.

Severe Pain Crisis

1. A severe pain crisis requires prompt

use of analgesics, adjuvant therapies, reassurance and a calm atmosphere.

2. Consider a consultation to palliative

care or a cancer pain specialist.

3. If IV access is present, and the person

is opioid naïve give stat morphine 5-

10 mg IV q10min until pain is

relieved; if the person is on opioids

give the po PRN dose IV q10min until

pain is relieved. Monitor carefully.

4. If no IV access available, and the

person is opioid naïve give stat

morphine 5-10 mg subcut q20-30min

until pain is relieved; if the person is

on opioids give the po PRN dose

subcut q20-30min until pain is

relieved.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 45

5. Titrate dose by 25% every 1 - 2 doses

until pain is relieved.

6. When pain is controlled: If the patient

is taking a sustained release opioid

increase this dose by 25% and change

to q4h dosing po or subcut. Do Not try

to manage a severe pain crisis with a

long-acting opioid. Change the

breakthrough dose to half of the

regular dose, either q1h PRN PO or

q30 min PRN subcut.

CONVERSION RATIOS

It should be noted that these conversion

ratios, based on available evidence, are conservative in the direction specified; if converting in the reverse direction, a reduction in dose of one third should be used following conversion, or specialist advice sought.

46 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

Approximate Equivalent

Parenteral

Fentanyl

Morphine

Oxycodone

Pethidine

Sufentanil

Tramadol

Methadone

a. From single dose studies using immediate-release dosage

forms. These approximate analgesic equivalences should be used only as a guide for estimating equivalent doses when switching from one opioid to another. Additional references should be consulted to verify appropriate dosing of individual agents.

b. Route of administration not applicable. c. With repeated dosing. d. Tramadol's precise analgesic potency relative to morphine

is not established. Consult the product monograph for dosing recommendations.

e. For methadone, se

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 47

Conversion doses from oral morphine to

transdermal fentanyl

Oral 24-hour

Transdermal Fentanyl

morphine (mg/day)

37 (if available, otherwise 25)

62 (if available, otherwise 50)

48 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

TITRATION GUIDE

General principles:

6.

Calculate the total opioid dose taken by the patient

in 24 h (regular q4h dose x 6 PLUS the total

number of breakthrough doses given x

breakthrough dose).

Divide this 24 h total by 6 for the equivalent q4h dose.

Divide the newly calculated q4h dose by 2 for the breakthrough dose.

Use clinical judgment regarding symptom control as to whether to round up or down the obtained result (both breakthrough and regular dosing). Remember to consider available dosage forms (in the case of PO medications especially).

10. If the patient is very symptomatic a review of how

many breakthrough doses have been given in the past few hours might be more representative of his/her needs.

Example:

A patient is ordered morphine 20 mg q4h PO and 10

mg PO q2h PRN, and has taken 3 breakthrough

doses in the past 24 h.

1.

Add up the amount of morphine taken in the past 24 h:

6 x 20 mg of regular dosing, plus 3 x 10 mg PRN doses equals a total of 150 mg morphine in 24 hours

Divide this total by 6 to obtain the new q4h dose:

150 divided by 6 = 25 mg q4h

Divide the newly calculated q4h dose by 2 to obtain the new breakthrough dose: 25 mg divided by 2 = 12.5 mg q1 - 2h PRN

If this dose provided reasonable symptom control, then order 25 mg PO q4h, with 12.5 mg PO q1 - 2h PRN. (It would also be reasonable to order 10 mg or 15 mg PO q2h for breakthrough.)

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 49

CONVERSION GUIDE

(To convert from long-acting preparations to

short-acting preparations)

General principles in converting from sustained

release to immediate release formulations (for the

same drug):

1. Add up the total amount of opioid used in the

past 24 h, including breakthrough dosing.

2. Divide this total by 6 to obtain equivalent q4h

3. Divide the q4h dose by 2 to obtain breakthrough

4. Use clinical judgment to adjust this dose up or

down depending on symptom control.

5. Consider available tablet sizes when calculating

Example:

A patient is ordered a long-acting morphine

preparation at a dose of 60 mg PO q12h, with 20

mg PO q4h for breakthrough, and has taken 4

breakthrough doses in 24 h.

1. Add up the amount of opioid taken in 24 h: 2 x

60 mg of long-acting morphine plus 4 x 20 mg of breakthrough is 200 mg of morphine in 24 h

2. Divide this total by 6 to obtain the equivalent q4h

dosing: 200 divided by 6 is approximately 33 mg PO q4h

3. Divide this q4h dose by 2 for the breakthrough

dose 33 mg divided by 2 is 16.5 mg

If the patient had reasonable symptom control with the previous regimen, then a reasonable order would be: 30 mg PO q4h and 15 mg q1 - 2h PO PRN

50 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide: Pain

Selected References:

1. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network SIGN

106, „Control of Cancer Pain in Adults with Cancer: A National Clinical Guideline‟ November 2008.

For full references and more information please refer to

Disclaimer:

Care has been taken by Cancer Care Ontario‟s Symptom

Management Group in the preparation of the information

contained in this pocket guide.

Nonetheless, any person seeking to apply or consult the

guide to practice is expected to use independent clinical

judgment and skills in the context of individual clinical

circumstances or seek out the supervision of a qualified

specialist clinician.

CCO makes no representation or warranties of any kind

whatsoever regarding their content or use or application and

disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 51

52 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Loss of Appetite

Definition of Terms

Diagnosis

Assessment

Treatment

Pharmacological Treatment

Selected References

Definition of Terms

The first step in managing this symptom will be validation of Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) score with patient. An understanding of primary cachexia and how it differs from anorexia is needed to establish whether you are dealing with anorexia, secondary cachexia or primary cachexia.

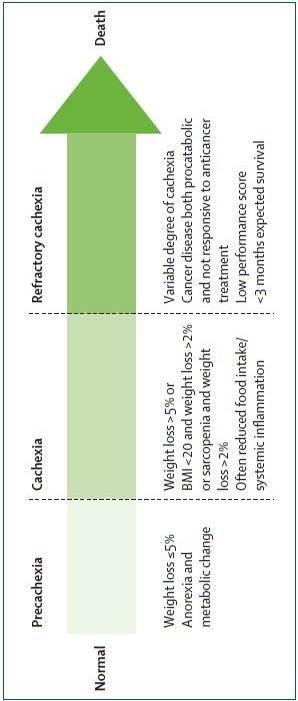

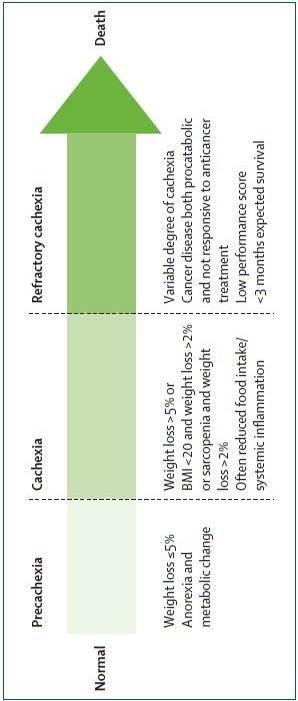

Definitions Anorexia is the loss of appetite or the desire to eat. Cancer Cachexia is a multifactorial syndrome characterized by an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass (with or without loss of fat mass) that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutrition support and leads to progressive functional impairment. Weight loss is evident. Losses associated with cancer cachexia are in excess of that explained by anorexia

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 53

alone; however anorexia can hasten the course of cachexia.

Secondary Cachexia: is characterized by potentially correctable causes that could explain the syndrome. Once identified, prompt intervention can greatly impact the patient‟s quality of life and overall

prognosis. Primary Cachexia should only be considered when all secondary causes have been identified and treated.

Sarcopenia is a condition characterized by loss of muscle mass and muscle strength. Patients presenting with loss of muscle mass, but no weight loss, no anorexia, and no measureable systemic inflammatory response may well be sarcopenic. Recent literature encourages the staging of primary cachexia to support patients and potentially improve the type and timing of treatment modalities (Figure 1).

54 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

xia: hecac r . er

t e ighon ra opyr

ia

xehcac yra

s oegtaS : 1erugFi

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 55

Diagnosis

Establish whether loss of appetite is related to

treatment side effects (e.g. radiation therapy,

chemotherapy, or surgical treatment), other

medication and/ or psychosocial factors. If these

factors are not deemed to be causative then tumor

related factors may be at work and determination of

the physical vs. metabolic factors should be further

considered. See table 1 for causes of anorexia and

secondary cachexia.

Description

Factors secreted by tumour (e.g.

tumour necrosis factor/cachectin,

interleukin-6, lipid-mobilizing factor, proteolysis-inducing factor) Metabolic and hormonal

abnormalities (e.g. alterations in

carbohydrate, lipid and protein

utilization synthesis and breakdown)

Taste and smell abnormalities or

Fatigue / malaise and asthenia (cycle

can occur in which decreased intake

leads to lethargy and weakness,

leading to a further decrease in oral intake) Gut involvement (e.g. intraluminal

gastrointestinal malignancy, gut

atrophy, partial bowel obstruction,

decreased production of digestive secretions, decreased peristalsis, constipation) Malabsorption Syndrome (fats and

carbohydrates not metabolized/

56 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Description

Infection (e.g. low grade sepsis)

Diarrhea (e.g. cytotoxic effects on

the gut mucosa/ radiation enteritis/

short bowel syndrome)

Taste and Smell abnormalities

Xerostomia (e.g. mucositis,

infection, poor hygiene,

dehydration, medication, taste bud alternation) Palliative gastrectomy

Systemic antineoplastic drugs (e.g.

chemotherapy, targeted therapy,

Antimicrobial agents

cide Antidepressants (e.g. selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as

fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram,

paroxetine; atypicals such as bupropion)

Fear of eating because of possibility

of making symptoms worse (e.g.

pain, incontinence, diarrhea,

constipation) or because of certain beliefs that eating will make the

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 57

Description

cancer, symptoms, or health worse.

Lack of emotional support

Lack of functional

support/independence Lack of financial resources/support

The causes of primary cachexia are also tumour-

related causes of anorexia:

factors secreted by tumour (e.g. tumour necrosis factor/cachectin, interleukin-6, lipid-mobilizing factor, proteolysis-inducing factor) , and

metabolic and hormonal abnormalities (e.g. alterations in carbohydrate, lipid and protein utilization synthesis and breakdown).

Assessment

Ongoing comprehensive assessment is the foundation of effective anorexia and cachexia management. An in-depth assessment should include:

review of medical history with current medication(s),

review of treatment plan/effects and clinical goals of care,

weight and diet history,

physical assessment,

available laboratory investigations, and

review of psychosocial and physical environment.

Consider the following validated tools for further screening and in-depth assessment:

58 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST)

Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA)

Percentage of weight loss over time evaluates malnutrition:

> or equal 5% loss of usual body weight in one month.

> or equal 7.5% loss of usual body weight in 3 months.

> or equal 10% loss of usual body weight in 6 months.

Non Pharmacological Treatment

Stage of disease, progression of disease and Palliative

Performance Scale (PPS), or functional status, should

be considered when determining goals of care and

treatment plans.

Psychosocial Strategies

Provide emotional support to patient and family.

Consider importance of food in the social context and impact on quality of life.

Consider cultural issues

Consider patient's accessibility to food.

Referral to other health care professionals where appropriate.

Nutrition Education Strategies

Provide nutrition-focused patient education for self-management early in symptom trajectory with a goal to improve or maintain nutritional and functional status via oral nutrition. •

Suggest eating small, frequent meals and choosing high energy, high protein foods. See Patient Education tools below.

Ensure adequate hydration, preferably through energy and protein containing liquids.

Suggest making mealtimes as relaxing and enjoyable as possible.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 59

Suggest convenience foods, deli or take-out foods, Meals on Wheels® or catering services, Home Making services, or asking friends/family to help out.

Taking medication with a high calorie / protein fluid such as milkshakes or nutrition supplements can also increase nutritional intake. This should be reviewed by a dietitian and/or pharmacist because of potential drug/nutrient interaction(s).

Nutritional supplements, as recommended by a dietitian and/or pharmacist.

Refer to a registered dietitian. See section below.

Patient Education tools:

•

Healthy Eating Using High Energy, High Protein Foods

High Energy and High Protein Menu items

Food ideas to help with poor appetite

Increasing Fluid Intake

Suggestions for Increasing Calories and Protein

Eating Well When You Have Cancer

Canada‟s Food Guide

Exercise Strategies

Encourage exercise, as tolerated by patient. Walking fifteen minutes a day can help regulate appetite.

Patient should start the exercise regimen slowly, and gradually increase intensity.

Exercise can be initiated at most levels above PPS 30-40% but caution should be guiding principle, as well as presence of bony metastases and low blood counts.

60 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Referral to a Registered Dietitian

Individualized dietary counseling has been shown to reduce incidence of anorexia and improve nutritional intake and body weight, as well as improve quality of life.

Non-Pharmacological Treatment specific to

Primary Cachexia: Refractory stage

Consider Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) scores, in conjunction with ESAS scores, to determine appropriateness and aggressiveness of interventions.

Assist families and caregivers to understand and accept benefits and limits of treatment interventions, and to look at alternate ways to nurture patient (oral care, massage, reading, conversing).

While underlying cause(s) may be evident, treatment may not be indicated.

Ice chips, small sips of beverages and good mouth care becomes norm.

Consider symbolic connection of food and eating with survival and life. Food may become a source of emotional distress experienced by both family and patient.

It is important to educate that a person may naturally stop eating and drinking as part of illness progression and dying process.

Focus should be on patient comfort and reducing patient and caregiver anxiety, as reversal of refractory cachexia is unlikely.

Recognize that discontinuation of nutrition is a value-laden issue. Consider consultation with

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 61

registered dietitian, spiritual counselor or bioethicist, to clarify clinical goals.

Referral to other health care professionals where appropriate.

Pharmacological Treatment

The following pharmacological treatments are

suggested to alleviate the symptom of loss of appetite

and may improve quality of life. They may affect

weight gain; however weight gain may be attributable

to water retention and/or fat, not muscle gain.

Appetite stimulants can be used in combination with or after failure of oral nutritional management.

Use of appetite stimulants is particularly warranted in patients with incurable disease. Appetite stimulants can be administered to patients with any type of tumour.

The optimal mode of administration for these products is not known.

Please refer to the drug table on next page.

62 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

can- g- h- i- cat- mu

Synthetic

Prokinetics

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 63

Selected References:

BC Cancer Agency. Nutritional Guidelines for Symptom Management: Anorexia [Internet]. 1996, updated 2005. [cited 21/12/2010] Available from:

Desport JC, Gory-Delabaere G, Blanc-Vincent MP, Bachmann P, Be´ al J, Benamouzig R, Colomb V, Kere D, Melchior JC, Nitenberg G, Raynard B, Schneider S, and Senesse P. FNCLCC Standards, Options and Recommendations for the use of appetite stimulants in oncology. British Journal of Cancer; 2000:89(Suppl 1):S98 – S100, doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601090.

Fraser Health Hospice Palliative Care Program. Symptom Guidelines: Nutrition and cachexia [Internet]. 2006. [cited 21/12/2010] Available from:

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker S, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, Jatoi A, Loprinzi C, Macdonald N, Mantovani G, Davis M, Muscaritoli M, Ottery F, Radbruch P, Walsh D, Wilcock A, Kaasa S, & Baracos V. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus . The Lancet; 2011; 12: 489-495.

For full references, links to tools, and more

information please refer to CCO's Symptom

Management Guide-to-Practice: Loss of Appetite

document (www.cancercare.on.ca/symptools).

64 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 65

66 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Bowel Care

Assessment …………………………………. 67

Diagnosis ………………………………………. 68

Non-Pharmacological Treatment… 68

Pharmacological Treatment …….… 72

Selected References …………………. 79

Assessment

Obtaining a detailed history, including assessment of functional status and goals of care, is an important step in identifying etiologic factors and appropriate management strategies for constipation and diarrhea.

Physical assessment should include vital signs, functional ability, hydration status, cognitive status, abdominal exam, rectal exam and neurological exam if a spinal cord or cauda equine lesion is suspected. Consider abdominal x-rays if bowel obstruction or severe stool loading of the colon is suspected.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 67

Diagnosis

Identifying the etiology of constipation and diarrhea is essential in determining the interventions required.

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

Constipation

Consider performance status, fluid intake,

diet, physical activity and lifestyle when

managing constipation.

General Education It is not necessary to have a bowel

movement every day. As long as stools are soft and easy to pass, every two days is generally adequate.

Avoid excessive straining.

In absence of oral intake, the body

continues to produce 1-2 ounces of stool per day.

PPS Stable, Transitional and End of Life (30-

100%)

Fluid Intake

Encourage intake of fluids throughout the

Aim for fluid intake between 1500-2000

For patients who are not able to drink large

volumes, encourage sips throughout the day.

Limit intake of caffeinated and alcoholic

beverages, as they may promote dehydration

68 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Physical Activity Physical activity should be tailored to the

individual‟s physical ability, health condition and personal preference, to optimize adherence.

Frequency, intensity and duration of

exercise should be based on the patient‟s tolerance.

For PPS 60% and above, walking is

recommended (e.g., 15-20 minutes once or twice per day or 30-60 minutes daily, 3-5 times per week).

For PPS 30-50% exercises such as low

trunk rotation and single leg lifts, for up to 15 to 20 minutes per day, are encouraged, if able.

Personal Considerations Provide privacy during toileting. Attempts at defecating should be made 30

to 60 minutes following ingestion of a meal, to take advantage of the gastro-colic reflex.

PPS Stable and Transitional (40-100%)

Diet

The following dietary recommendations are

not applicable if bowel narrowing or obstruction is suspected.

Dietary fibre intake should be gradually

increased once the patient has a consistent fluid intake of at least 1500 ml per 24 hours.

Aim for dietary fibre intake of at least 25

grams per day (choose 7-10 servings per day of whole fruits and vegetables, instead of juices, choose 6-8 servings of grain

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 69

products per day, 100% whole grain breads and high fibre cereals, plant proteins daily as part of the 2-3 servings of meats and alternatives).

Fruit laxative (125 ml pitted dates, 310 ml

prune nectar, 125 ml figs, 200 ml raisins,125 ml pitted prunes).

Consult with a dietitian for specific

nutritional advice regarding fibre intake.

Personal Considerations Walking to the toilet, if possible, is

recommended. If walking is difficult, use a bedside commode.

Assuming the squat position on the toilet

can facilitate the defecation process.

o Sitting with feet on a stool may help

with defecation.

PPS End of Life (10-30%)

Raising the head of the bed may facilitate

the defecation process.

Simulate the squat position by placing the

patient in the left-lateral decubitus position, bending the knees and moving the legs toward the abdomen.

PPS End of Life (10-20%)

For patients with PPS 10-20%, consider the

burdens and benefits of regular bowel care, using good clinical judgment when making recommendations.

Diarrhea

Consider performance status, diet, fluid

intake, quality of life and lifestyle when

managing diarrhea.

70 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

PPS Stable, Transitional and End of Life (30-

100%)

Diet

Eat small frequent meals.

Limit consumption of caffeine, fried,

greasy foods and foods high in lactose.

Avoid sorbitol containing foods (e.g.,

sugar-free gum and sugar-free candy).

Limit/avoid foods high in insoluble fiber

(e.g., wheat bran, fruit skins and root vegetable skins, nuts and seeds, dark leafy greens and legumes such as dried peas).

Include foods high in soluble fibre (barley,

potatoes, bananas and applesauce).

Avoid hyper-osmotic liquids (fruit drinks

and sodas). Dilute fruit juices with water.

Fluid Intake Parenteral hydration may be required for

Provide fluids orally, if dehydration is not

An oral rehydration solution can be

prepared by mixing 1/2 teaspoon salt and 6 level teaspoons sugar in 1 litre of tap water.

Commercially available oral rehydration

solutions containing appropriate amounts of sodium, potassium and glucose can be used.

PPS Stable, Transitional and End of Life (10-

100%)

Quality of Life

Persistent diarrhea can have severe effects

on image, mood and relationships.

Attention must be paid to understanding the

emotional impact from the patient‟s perspective.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 71

Offer practical strategies to assist with

coping: carefully plan all outings, carry a change of clothes, know the location of restrooms, use absorbent undergarments.

Life style Take steps to prevent skin excoriation:

o Use mild soap, consider sitz bath. o Apply a skin barrier product.

Hydrocolloid dressings may be used as a

physical barrier to protect excoriated skin.

PPS End of Life (10-20%)

Exercise good clinical judgment regarding the

burden and benefits of parenteral fluids for the

individual patient

Pharmacological Treatments

Ask patient whether using non-traditional

or alternative therapies for bowel management.

Consider the etiology of constipation or

diarrhea before initiating any pharmacological treatment.

Constipation

Consider the patient's preferences and

previous

experiences

management when determining a bowel

regimen.

Consider the patient's recent bowel function

and response to previous treatments to guide

appropriate selection and sequence of

pharmacological treatments.

72 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Recommended first line agents

Oral colonic stimulant (sennosides or bisacodyl)

Oral colonic osmotic (lactulose or polyethylene

Recommended second line agents

Suppositories (glycerin or bisacodyl)

Enemas (phosphate enema)

Recommended third line (rescue) agents

Picosulfate sodium-magnesium oxide-citric acid

Methylnaltrexone (if the patient is taking regular

opioids)

Fecal Impaction If stool is impacted in the rectum, use a

glycerin suppository to soften the stool, followed 1 hour later by digital disimpaction, if necessary (after pretreatment with analgesic and sedative), and/or a phosphate enema.

If stool is higher in the left colon, use an oil

retention enema, followed by a large volume enema at least 1 hour later.

Constipation Management in Special Circumstances

Opioid-induced constipation is much easier

to prevent than to treat. Start a first line oral

laxative on a regular basis for all patients

taking opioids.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 73

Initial 3-Day Trial of methylnaltrexone

If no bowel movement for 48 hours, give

methylnaltrexone subcutaneously - 8 mg if 38-62 kg

or 12 mg if 62-114 kg

ethylnaltrexone is considered effective if a bowel

ovement occurs within 4 hours after injection.

Effective

Effective

The same dose can be repeated every 24

hours for 2 days, if necessary, if a bowel

movement does not subsequently occur

NOT

Effective

Effective

Methylnaltrexone is

The same dose can be

unlikely to work for

offered in the future if no

this patient at this

bowel movement occurs for

time. No further

48 hrs. Doses should not be

given more frequently than

h lnaltre

74 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Patients with a Colostomy

Use the same approach to bowel care as for

the patient without a colostomy. A patient with a very proximal colostomy may not benefit from colonic laxatives.

There is no role for suppositories since they

cannot be retained in a colostomy.

Enemas may be useful for patients with a

descending or sigmoid colostomy.

Paraplegic Patients A patient with paraplegia is unable to

voluntarily evacuate the rectum.

Passage of stool spontaneously may

represent overflow only.

As for patients without paraplegia, oral

laxatives may be needed to move stool to the rectum, but the paraplegic patient needs help to empty the rectum. o Schedule a rectal exam daily or every 2

days, depending on the patient‟s preference, followed, if necessary, by assistance emptying the rectum using one or more of the following: suppository enema digital emptying

Develop an effective, regular protocol that

is acceptable to the patient.

Table 1 and 2 below offer additional information on oral and rectal laxatives available in Canada.

CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide 75

Table 1. Oral Laxatives

Bisacodyl

increase up to 15 mg tid

Lactulose

ntly softening, secondarily stimulant

Picosulfate

citric acid

until good effect

ne glycol

Sennosides Colonic

to 4 tablets or 20 ml bid

Notes: bid = twice daily; gm = grams; mg = milligrams; ml = milliliter; qhs = every night at bedtime; tid = three times a day.

76 CCO‟s Symptom Management Pocket Guide

Table 2. Rectal Laxatives

Rectal or

Bisacodyl

suppository stimulating

Glycerin

dilation and Normal

stimulation; saline

(tap water

or saline)

retention

Phosphate

solution in pre-packed bottles

Notes: mg = milligrams; ml = milliliters; prn = as required;

Diarrhea

A single liquid or loose stool usually does not

require intervention.

A single drug should be used for diarrhea