Emergency department diagnosis and treatment of anaphylaxis: a practice parameter

Contents lists available at

Practice Parameter

Emergency department diagnosis and treatment of anaphylaxis:a practice parameter

Ronna L. Campbell, MD, PhD; James T.C. Li, MD, PhD; Richard A. Nicklas, MD; Annie T. Sadosty, MDMembers of the Joint Task Force: David Bernstein, MD; Joann Blessing-Moore, MD;David Khan, MD; David Lang, MD; Richard Nicklas, MD; John Oppenheimer, MD; Jay Portnoy, MD;Christopher Randolph, MD; Diane Schuller, MD; Sheldon Spector, MD; Stephen Tilles, MD;Dana Wallace, MDPractice Parameter Workgroup: Ronna L. Campbell, MD, PhD; James T.C. Li, MD, PhD; Annie T. Sadosty, MD

This parameter was developed by the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters, representing the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; the American Collegeof Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; and the Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.

Disclaimer: The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) have jointlyaccepted responsibility for establishing "Emergency Department Diagnosis and Treatment of Anaphylaxis." This is a complete and comprehensive document at the currenttime. The medical environment is a changing environment, and not all recommendations will be appropriate for all patients. Because this document incorporated theefforts of many participants, no single individual, including those who served on the Joint Task Force, is authorized to provide an official AAAAI or ACAAI interpretation ofthese practice parameters. Any request for information about or an interpretation of these practice parameters by the AAAAI or ACAAI should be directed to the ExecutiveOffices of the AAAAI, the ACAAI, and the Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. These parameters are not designed for use by pharmaceutical companies in drugpromotion.

Reprints: Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, 50 N Brockway Street, #3-3, Palatine, IL 60067.

Published practice parameters of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters for Allergy and Immunology are available online at and Disclosures: The Joint Task Force recognizes that experts in a field are likely to have interests that could come into conflict with development of a completely unbiased andobjective practice parameter. To take advantage of that expertise, a process has been developed to prevent potential conflicts from influencing the final document in anegative way. At the workgroup level, members who have a potential conflict of interest do not participate in discussions concerning topics related to the potential conflict,or if they do write a section on that topic, the workgroup completely rewrites it without their involvement to remove potential bias. In addition, the entire document isreviewed by the Joint Task Force and any apparent bias is removed at that level. The practice parameter is sent for review by invited reviewers and by anyone with aninterest in the topic by posting the document on the Web sites of the ACAAI and the AAAAI.

Contributors: The Joint Task Force has made a concerted effort to acknowledge all contributors to this parameter. If any contributors have been excluded inadvertently, theJoint Task Force will ensure that appropriate recognition of such contributions is made subsequently.

Workgroup Chairs, Ronna L. Campbell, MD, PhD; James T. Li, MD, PhD; Joint Task Force Liaison, Richard A. Nicklas, MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, GeorgeWashington Medical Center, Washington, DC; Joint Task Force Members, David I. Bernstein, MD, Professor of Clinical Medicine and Environmental Health, Division ofAllergy/Immunology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio; Joann Blessing-Moore, MD, Adjunct Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics, StanfordUniversity Medical Center, Department of Immunology, Palo Alto, California; David A. Khan, MD, Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, University of TexasSouthwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas; David M. Lang, MD, Head, Allergy/Immunology Section, Division of Medicine, Director, Allergy and Immunology FellowshipTraining Program, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio; Richard A. Nicklas, MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, George Washington Medical Center, Washington,DC; John Oppenheimer, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, New Jersey Medical School, Pulmonary and Allergy Associates, Morristown, New Jersey; Jay M. Portnoy,MD, Chief, Section of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, The Children's Mercy Hospital, Professor of Pediatrics, University of MissourieKansas City School of Medicine,Kansas City, Missouri; Christopher C. Randolph, MD, Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, Yale Affiliated Hospitals, Center for Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology, Waterbury,Connecticut; Diane E. Schuller, MD, Professor of Pediatrics, Pennsylvania State University Milton S. Hershey Medical College, Hershey, Pennsylvania; Sheldon L. Spector,MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California; Stephen A. Tilles, MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of WashingtonSchool of Medicine, Redmond, Washington; Dana Wallace, MD, Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine,Davie, Florida; Parameter Workgroup Member, Annie T. Sadosty, MD; Assigned Reviewers: Estelle Simons, MD, Winnepeg, Manitoba, Canada; Marcella Aquino, MD,Mineola, New York.

1081-1206/Ó 2014 American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

Classification of recommendations and evidence

Recommendation rating scale

Strong recommendation

A strong recommendation means the benefits of the recommended

Clinicians should follow a strong recommendation unless a clear

approach clearly exceed the harms (or that the harms clearly

and compelling rationale for an alternative approach is present.

exceed the benefits in the case of a strong negativerecommendation) and that the quality of the supporting evidenceis excellent (grade A or B)*. In some clearly identifiedcircumstances, strong recommendations may be made based onlesser evidence when high-quality evidence is impossible toobtain and the anticipated benefits strongly outweigh the harms.

A recommendation means the benefits exceed the harms (or that

Clinicians also should generally follow a recommendation but

the harms clearly exceed the benefits in the case of a negative

should remain alert to new information and sensitive to patient

recommendation), but the quality of evidence is not as strong

(grade B or C).* In some clearly identified circumstances,recommendations may be made based on lesser evidence whenhigh-quality evidence is impossible to obtain and the anticipatedbenefits outweigh the harms.

An option means that the quality of evidence that exists is suspect

Clinicians should be flexible in their decision making regarding

(grade D)* or that well-done studies (grade A, B, or C)* show little

appropriate practice, although they may set bounds on

clear advantage to one approach vs another.

alternatives; patient preference should have a substantialinfluencing role.

No recommendation

No recommendation means there is a lack of pertinent evidence

Clinicians should feel little constraint in their decision making and

(grade D)* and an unclear balance between benefits and harms.

be alert to new published evidence that clarifies the balance ofbenefit vs harm; patient preference should have a substantialinfluencing role.

Category of evidence

Protocol for finding evidence

Ia Evidence from meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

A search of the medical literature was performed for different

Ib Evidence from at least 1 randomized controlled trial

terms that were considered relevant to this practice parameter.

Literature searches were performed on PubMed and the Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews. All reference types were included

IIb Evidence from at least 1 other type of quasi-experimental study

in the results. References identified as relevant were searched for

III Evidence from nonexperimental descriptive studies, such as

relevant references and those references also were searched for

comparative studies

relevant references. In addition, members of the workgroup were

IV Evidence from expert committee reports or opinions or clinical

asked for references that were missed by this initial search.

experience of respected authorities or both

Strength of recommendation*

A Directly based on category I evidence

This practice parameter is a joint effort between emergency

B Directly based on category II evidence or extrapolated recom-

physicians, who are often on the front line in the management of

mendation from category I evidence

anaphylaxis, and allergists-immunologists, who have a vested in-

C Directly based on category III evidence or extrapolated

terest in how such patients are managed. As recognized by emer-

recommendation from category I or II evidence

gency physicians and allergists, the timely administration of

D Directly based on category IV evidence or extrapolated

epinephrine is essential to the effective treatment of anaphylaxis,

recommendation from category I, II, or III evidence

and such administration is dependent on correctly diagnosing

LB Laboratory based

anaphylaxis. In an emergency department (ED) setting, with the

broad and often atypical presentation of anaphylaxis, failure torecognize anaphylaxis is a real possibility. Failure to recognize

Emergency department diagnosis and management of

anaphylaxis inherently leads to undertreatment with epinephrine.

anaphylaxis: a practice parameter

Studies have shown that a large percentage of patients (57%) whopresent to the ED with anaphylaxis can be

The Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters

Moreover, even when correctly diagnosed, epinephrine, the

The Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters is a 13-member task

essential first line in the treatment of anaphylaxis, is frequently (up

force consisting of 6 representatives assigned by the American

to 80% of the time) not administIn addition, patients who

Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; 6 by the American

are treated in the ED for anaphylaxis, frequently do not receive a

College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; and 1 by the Joint

prescription for auto-injectable epinephrine and usually are not

Council of Allergy and Immunology. This task force oversees the

referred for allergy follow-up.

development of practice parameters; selects the workgroup

The recommendations made in this document about the man-

chair(s); and reviews drafts of the parameters for accuracy, prac-

agement of anaphylaxis apply to anaphylaxis that occurs in an ED

ticality, clarity, and broad utility of the recommendations for clin-

setting. Some of these recommendations might be different if

ical practice.

anaphylaxis occurs in an office setting.

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

It is important to understand that there is no absolute contra-

condition. Obtain a serum tryptase level to assist in this regard

indication to administration of epinephrine in the setting of

after effective treatment has been rendered. (Moderate

anaphylaxis. It also is important to recognize that anaphylaxis can

Recommendation; C Evidence)

progress rapidly from mild manifestations involving 1 organ sys-

Summary Statement 6: Determine whether the patient has risk

tem to severe involvement of multiple organ systems.

factors for severe and potentially fatal anaphylaxis, such asdelayed administration of epinephrine, asthma, a history ofbiphasic reactions, or cardiovascular disease, and consider these

Compilation of summary statements

in the management and/or disposition of all patients with

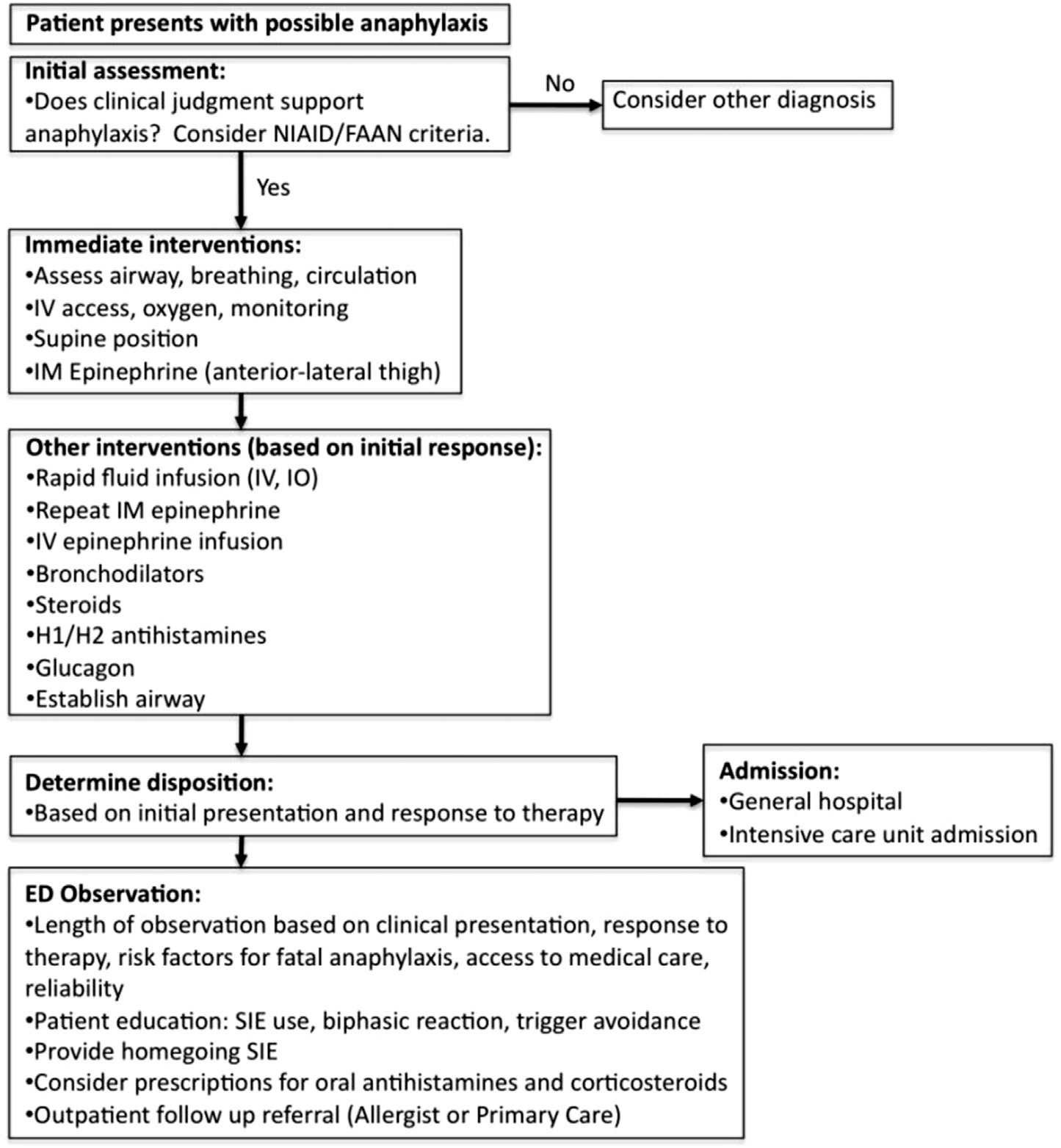

Summary Statement 1: Base the diagnosis of anaphylaxis on the

anaphylaxis. (Moderate Recommendation; B Evidence)

history and physical examination, using scenarios described by

Summary Statement 7: Administer epinephrine intramuscularly

the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID)

in the anterolateral thigh as initial treatment for acute anaphy-

Panel (but recognizing that there is a broad spectrum of

laxis immediately after the diagnosis of anaphylaxis is made. The

anaphylaxis presentations that require clinical judgment. Do not

first line of treatment for patients experiencing anaphylaxis is

rely on signs of shock for the diagnosis of anaphylaxis. (Strong

epinephrine. (Strong Recommendation; B Evidence)

Recommendation; C Evidence)

Summary Statement 8: If the patient is not responding to

Summary Statement 2: Carefully and immediately triage and

epinephrine injections, administer an intravenous (IV) infusion

monitor patients with signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis in

of epinephrine in a monitored setting. (Moderate Recommen-

preparation for epinephrine administration. (Strong Recom-

dation; C Evidence)

mendation; C Evidence)

Summary Statement 9: If IV access is not readily available in

Summary Statement 3: In general, place patients in a supine

patients experiencing anaphylaxis, obtain intraosseous (IO) ac-

position to prevent or counteract potential circulatory collapse.

cess and administer epinephrine by this route. (Moderate

Place pregnant patients on their left side. (Moderate Recom-

Recommendation; D Evidence)

mendation; C Evidence)

Summary Statement 10: Prepare for airway management,

Summary Statement 4: Administer oxygen to any patient

including intubation if necessary, if there is any suggestion of

exhibiting respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms or patients

airway edema (eg, hoarseness or stridor) or associated respira-

with decreased oxygen saturation and consider for all patients

tory compromise. (Moderate Recommendation; C Evidence)

experiencing anaphylaxis regardless of their respiratory status.

Summary Statement 11: For patients with circulatory collapse

(Moderate Recommendation; D Evidence)

from anaphylaxis, aggressively administer large volumes of IV or

Summary Statement 5: Expeditiously consider conditions other

IO normal saline through large-bore catheters. (Strong Recom-

than anaphylaxis that might be responsible for the patient's

mendation; B Evidence)

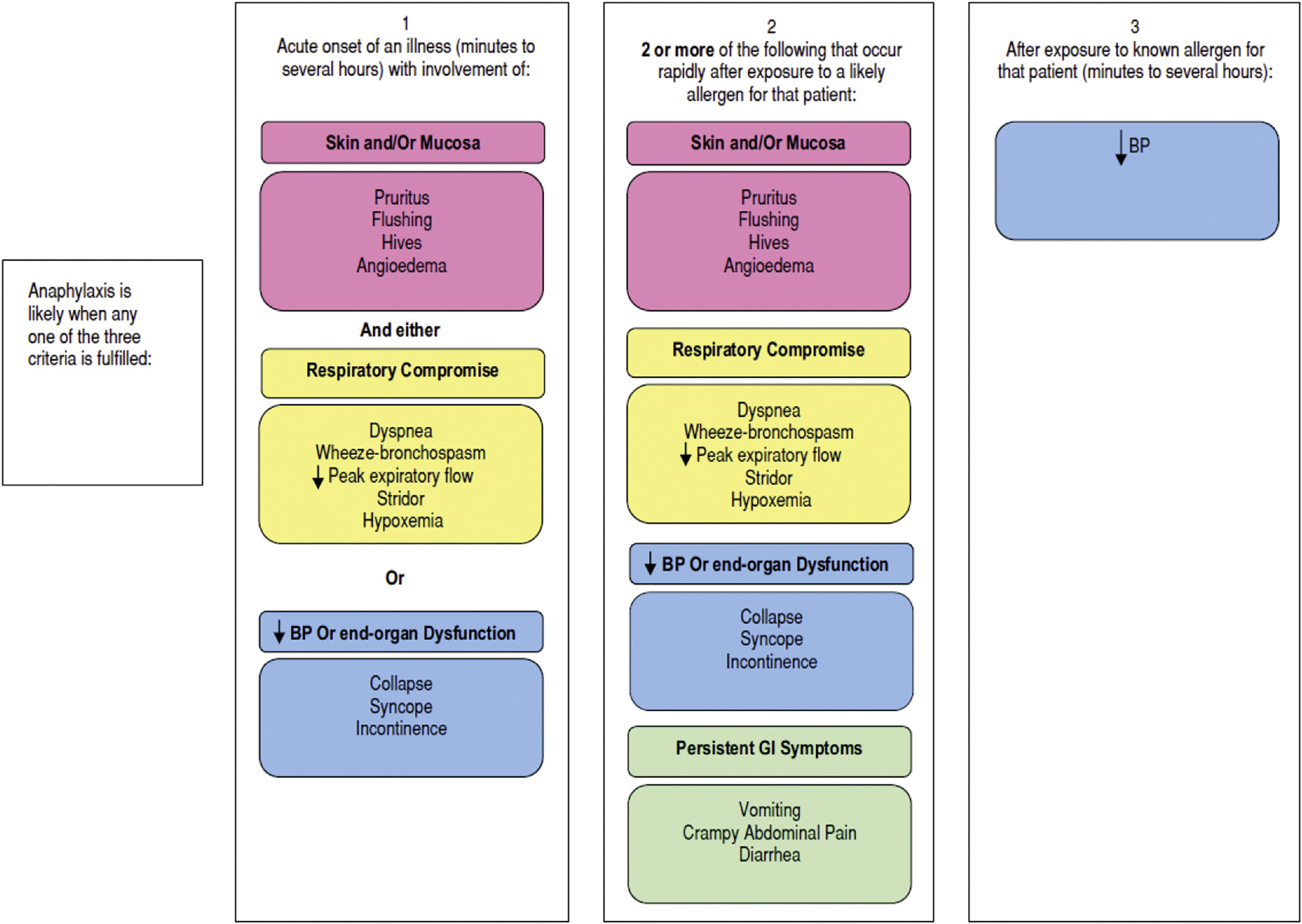

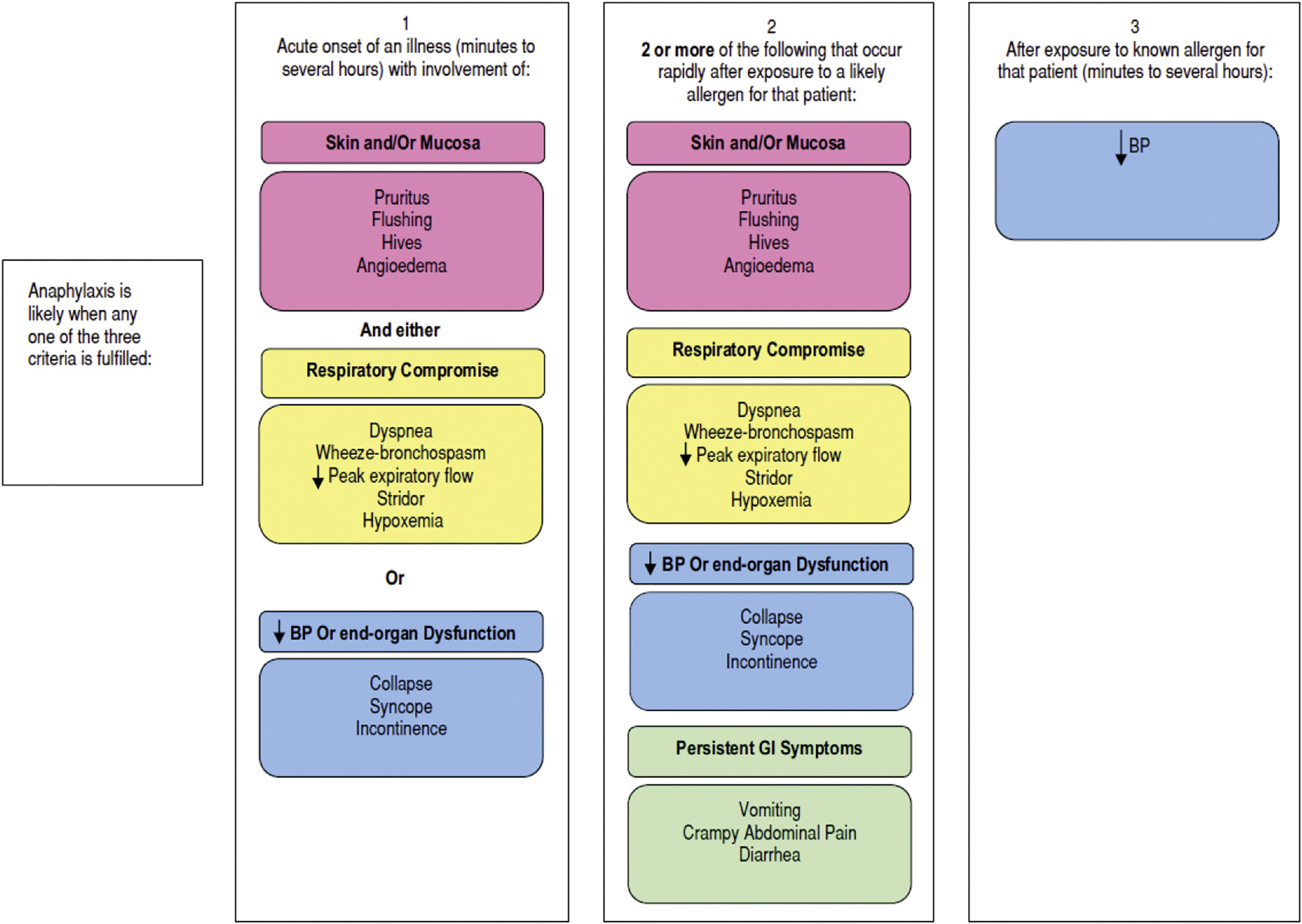

Figure 1. Visual representation of the NIAID/FAAN criteria. Reprinted with permission from the Internal Journal of Emergency Medicine.

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

Summary Statement 12: Administer additional vasopressors or

have a history of severe reactions.Although most cases of

glucagon (especially if the patient is receiving b-blockers) if

anaphylaxis will include cutaneous manifestations, the absence of

parenteral epinephrine and fluid resuscitation fail to restore

skin manifestations does not exclude a diagnosis of anaphylaxis.

blood pressure. (Moderate Recommendation; B Evidence)

Summary Statement 2: Carefully and immediately triage and

Summary Statement 13: Administer an inhaled b-agonist if

monitor patients with signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis in

bronchospasm is a component of anaphylaxis. (Moderate

preparation for epinephrine administration. (Strong Recom-

Recommendation; B Evidence)

mendation; D Evidence)

Summary Statement 14: Consider extracorporeal membraneoxygenation in patients with anaphylaxis who are unresponsive

Anaphylaxis can progress rapidly and become life threatening.

to traditional resuscitative efforts. (Moderate Recommendation;

monitoring, is essential for patients who are experiencing

Summary Statement 15: Do not routinely administer antihista-

anaphylaxis. This should include blood pressure, continuous pulse

mines or corticosteroids instead of epinephrine. There is no

rate, pulse oximetry, and electrocardiographic monitoring. IV ac-

substitute for epinephrine in the treatment of anaphylaxis.

cess should be obtained as soon as possible. These measures should

Administration of H1 and/or H2 antihistamines and corticoste-

be used to monitor response to therapy and direct subsequent

roids should be considered adjunctive therapy. (Strong Recom-

mendation; B Evidence)Summary Statement 16: Identify triggers of anaphylaxis and

Summary Statement 3: In general, place patients in a supine

consider obscure and less common triggers. (Moderate

position to prevent or counteract potential circulatory collapse.

Recommendation; C Evidence)

Place pregnant patients on their left side. (Moderate Recom-

Summary Statement 17: Strongly consider observing patients

mendation; C Evidence)

who have experienced anaphylaxis for at least 4 to 8 hours andobserve patients with a history of risk factors for severe

A case series on anaphylactic deaths has suggested an associa-

anaphylaxis, such as asthma, previous biphasic reactions, or

tion between upright posture and To counteract the cir-

protracted anaphylaxis, for a longer period (Moderate Recom-

culatory collapse of anaphylaxis, patients generally should be

mendation; C Evidence)

placed in a supine position. However, patients in respiratory

Summary Statement 18: Prescribe auto-injectable epinephrine

distress could benefit from being in a more upright position while

for patients who have experienced an anaphylactic reaction and

they are monitored carefully for any circulatory collapse. Although

provide patients with an action plan instructing them on how

Trendelenburg positioning has long been proposed to prevent or

and when to administer epinephrine. (Strong Recommendation;

counteract hypotension, there is no evidence to support Trende-

lenburg positioning and it might even be counterproductiv

Summary Statement 19: Instruct patients who have experienced

Pregnant patients should be placed on their left side to prevent

anaphylaxis when discharged from the ED to see an allergist-

the gravid uterus from compressing the inferior vena cava and

immunologist. (Moderate Recommendation; C Evidence)

obstructing venous return to the heart. Gentle manual displace-ment of the uterus may be necessary. The patient should not sit orstand suddenly because of the possibility of cardiac arrest caused

ED diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis: a practice

by the empty inferior vena cava syndrome.

Summary Statement 4: Administer oxygen to any patient

Summary Statement 1: Base the diagnosis of anaphylaxis on the

exhibiting respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms or patients

history and physical examination, using scenarios described by

with decreased oxygen saturation and consider for all patients

the NIAID Panel () but recognizing that there is a broad

experiencing anaphylaxis regardless of their respiratory status.

spectrum of anaphylaxis presentations that require clinical

(Moderate Recommendation; D Evidence)

judgment. Do not rely on signs of shock for the diagnosis ofanaphylaxis. (Moderate Recommendation; C Evidence)

Summary Statement 5: Expeditiously consider conditions otherthan anaphylaxis that might be responsible for the patient's

Symptoms of anaphylaxis are usually sudden in onset and can

condition. Obtain a serum tryptase level to assist in this regard

progress in severity over minutes to hours. Typically, at least 2 organ

after effective treatment has been rendered. (Moderate

systems are involved, although only 1 organ system might be

Recommendation; C Evidence)

initially involved. There is a broad spectrum of anaphylaxis pre-sentations that require clinical judgment. Although no set of diag-

The differential diagnosis of anaphylaxis is broad. In the study

nostic criteria for anaphylaxis will provide 100% sensitivity and

noted in summary statement 1, the negative predictive value of the

specificity, the criteria developed by the NIAID Panel in 2004 have

proposed NIAID criteria was 98%, but the positive predictive value

been shown to aid in the diagnosis of anaphy(The ac-

was only 69%, showing that a significant number of patients who

curacy of these criteria were retrospectively evaluated in an ED

meet the criteria might not have anaphylaxis. The physician cannot

setting and found to have 97% sensitivity and 82% specificityThe

rely on the presence of shock to make a diagnosis of anaphylaxis. It is

negative predictive value was 98% and the positive predictive value

important to consider other conditions that could be responsible for

was 69%; the positive likelihood ratio was 5.48, with a negative

the patient's presentation: (1) cardiogenic, distributive, obstructive,

likelihood ratio of 0.04. Therefore, these criteria are useful but do

or hypovolemic shock; (2) pre-syncope or syncope; (3) hereditary

not replace clinical judgment. It is important for health care pro-

angioedema or angioedema induced by an angiotensin-converting

viders to recognize the variable presentation and progression of

enzyme inhibitor; (4) vocal cord dysfunction; (5) flushing such as

anaphylaxis.Recognizing milder anaphylaxis is important not

occurs associated with metastatic carcinoma or vasoactive intestinal

only in preventing progression of a specific event to a more serious

peptide-producing tumor; (6) respiratory distress from asthma,

outcome but in preventing recurrent episodes in the future.

pulmonary embolism, congestive heart failure, or other causes; (7)

Although anaphylaxis can present as hypotension alone, it

isolated skin reactions, such as those that can be seen with adverse

frequently presents without hypotension. Studies of fatal and near-

drug reactions; (8) mast cell disorders, as discussed below; and (9)

fatal anaphylaxis have shown that most of these patients did not

psychiatric disorders, such as panic attacks.

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

Serum tryptase is a marker of mast cell degranulation and could

management.Epinephrine was administered only before arrest

be useful for confirming the diagnosis of anaphylaxis. Thus, the ED

in 14% of patients, and overall, only 62% received

physician should consider obtaining a tryptase level if appropriate

Patients with anaphylaxis can present with symptoms not

follow-up of the test result can be assured (eg, with the patient's

meeting the criteria for anaphylaxis and yet require administration

primary care physician or by an allergist who agrees to see the

of epinephrine, such as a patient with a history of near-fatal

patient in follow-up. Because serum tryptase levels are not rapidly

anaphylaxis to peanut who inadvertently ingests peanut and

available, management of a patient with possible anaphylaxis

within minutes is experiencing urticaria and generalized flushing.

should never be based on serum tryptase levels alone. However,

Delayed administration of epinephrine is associated with poor

when the diagnosis of anaphylaxis is uncertain, a serum tryptase

outcomes and mortality.It is important to recognize that there is

level could aid at follow-up in the diagnosis of anaphylaxis in a

a broad spectrum of anaphylaxis presentations that require clinical

given patient. The sensitivity of serum tryptase in patients who

judgment in any given patient. The management of a patient who

present to the ED with acute allergic reactions is low (21% in 1

presents with symptoms of anaphylaxis 15 minutes after exposure

study).Moreover, serum tryptase level is not elevated in most

to the suspected trigger might be handled differently than the

patients who develop anaphylaxis from However, a small

patient who was exposed 2 hours previously. Because anaphylaxis

study using serial measurements of tryptase 15 and 60 minutes

can be self-limited, patients can present at a point when symptoms

after a sting challenge found that an increase of at least 2.0 mg/L had

have nearly resolved and might no longer require epinephrine for

a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of Serum tryptase levels

acute management. However, the patient who presents with acute

typically begin to increase approximately 30 minutes after the

symptoms of anaphylaxis should immediately receive epinephrine

onset of the reaction, peak 1 to 2 hours after the onset of the re-

even if the initial symptoms are not life threatening, because

action, and remain elevated for up to at least 6 to 8

anaphylaxis can progress rapidly from mild symptoms to severelife-threatening symptoms.

Summary Statement 6: Determine whether the patient has risk

The management of anaphylaxis also can depend on the setting

factors for severe and potentially fatal anaphylaxis, such as

in which symptoms of anaphylaxis develop. For example, the pa-

delayed administration of epinephrine, asthma, a history of

tient who presents to the ED with urticaria 2 hours after eating

biphasic reactions, or cardiovascular disease, and consider them

shrimp might not require an injection of epinephrine. In contrast, a

in the management and/or disposition of all patients with

patient known to be allergic to shrimp who presents with symp-

anaphylaxis. (Moderate Recommendation; B Evidence)

toms consistent with upper airway obstruction 2 hours after eatingshrimp should receive an injection of epinephrine. The recom-

Patients at risk of severe anaphylaxis include those with (1)

mended dosage of epinephrine in a setting where an exact does can

peanut and tree nut allergy, especially adolescents; (2) pre-existing

be drawn up is 0.01 mg/kg (maximum dose, 0.5 mg) administered

respiratory or cardiovascular disease; (3) asthma; (4) delayed

intramuscularly every 5 to 15 minutes as necessary to control

administration of epinephrine; (5) previous biphasic anaphylactic

symptoms. The 5-minute interval between injections can be liber-

reactions; (6) advanced age; and (7) mast cell

alized to permit more frequent injections as determined by the

Studies of fatal and near-fatal anaphylaxis have identified

important risk factors for fatal anaphylaxis. Based on a national

There are no randomized controlled studies of epinephrine

registry, several risk factors for fatal anaphylaxis from foods have

during anaphylaxis, including pharmacokinetic studies. A phar-

been identifiMost patients have been shown to be adolescents

macokinetic study in children not experiencing anaphylaxis

or young adults, most have been allergic to peanuts or tree nuts,

showed that epinephrine administered intramuscularly into the

most have had a history of asthma, and very few have had

anterolateral thigh resulted in a higher and more rapid peak plasma

epinephrine administered in a timely mannerCauses of fatal

concentration compared with subcutaneous administration in the

anaphylaxis are presented in

arm.A subsequent study in adults not experiencing anaphylaxis

Summary Statement 7: Administer epinephrine intramuscularly

showed that peak plasma epinephrine concentrations were higher

in the anterolateral thigh as initial treatment for acute anaphy-

and achieved faster after administration of epinephrine intramus-

laxis immediately after the diagnosis of anaphylaxis is made. The

cularly in the thigh compared with when it was administered

first line of treatment for patients experiencing anaphylaxis is

intramuscularly or subcutaneously in the Subcutaneous

epinephrine. (Strong Recommendation; B Evidence)

administration in the thigh has not been studied.

The physiologic effects of epinephrine include vasoconstriction,

The decision to initiate specific treatment for anaphylaxis re-

cardiac chronotropic and inotropic effects, bronchodilatation, and

quires clinical judgment. However, when the patient is experiencing

suppression of the release of histamine and other mediators form

ongoing symptoms that are consistent with acute anaphylaxis, the

mast cells and basophils, resulting in increased cardiac output,

patient should receive epinephrine promptly. In a study of fatal food-

increased peripheral vascular resistance, and decreased mucosal

induced anaphylaxis in the United Kingdom, the median time to

edema and airway resi

respiratory or cardiac arrest was 30 minutes. The median time to

Complications associated with parenteral administration of

arrest in Hymenoptera venom-induced anaphylaxis has been shown

epinephrine, other than IV administration, are very rare. There are

to be 15 minutes and the median time to arrest in medication-

no absolute contraindications for the administration of epinephrine

induced anaphylaxis in a hospital setting has been shown to be 5

in the setting of anaphylaxis. Nevertheless, a significant percentage

minutes, thus underscoring the need for rapid recognition and

of patients treated for anaphylaxis do not receive

Summary Statement 8: If the patient is not responding

to epinephrine injections, administer an IV infusion of

Causes of fatal anaphylaxis

epinephrine in a monitored setting. (Moderate Recommenda-

tion; C Evidence)

If the patient is not responding to epinephrine injections, careful

administration of an IV infusion of epinephrine in a monitored

Abbreviation: RCM, radiocontrast media.

setting might be necessary. A 1:1,000,000 infusion solution,

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

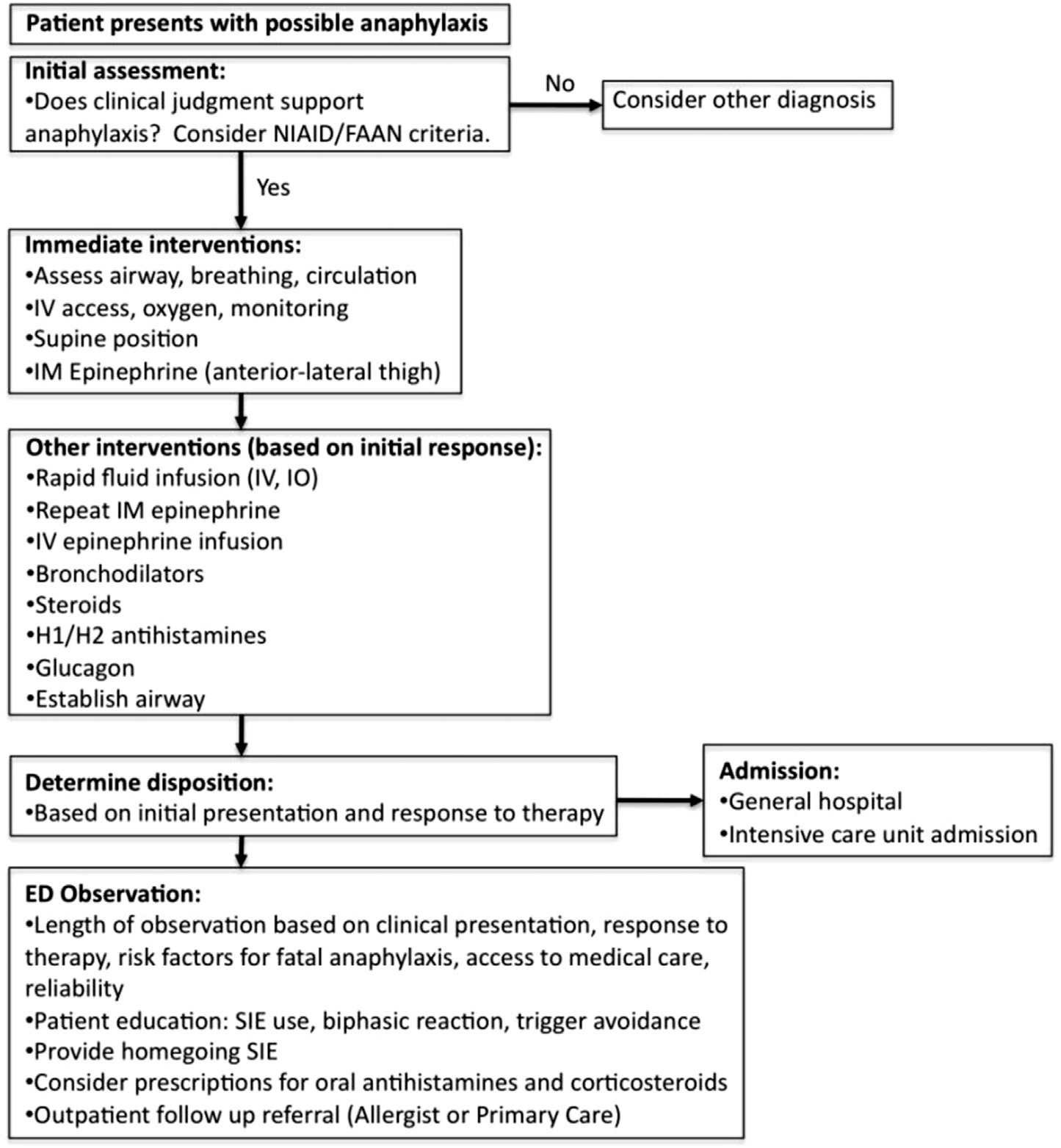

Figure 2. Emergency anaphylaxis management algorithm.

prepared by adding 1 mg (1 mL) of a 1:1,000 concentration of

Endotracheal administration of epinephrine also can be

epinephrine to 1000 mL of 5% dextrose in water or normal saline to

considered in patients in whom IV access is not possible. Anec-

produce a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL, can be infused at a rate of

dotally, successful reports when using alternative routes have been

1 mg/min and titrated to the necessary hemodynamic response and

reported. These include inhaled, sublingual, and endotracheal use

in adults and adolescents increased to a maximum of 10.0 mg/min. A

of epinephrine.

starting dose of 0.1 mg/kg per minute is recommended for children.

Bolus administration of IV epinephrine is associated with an

Summary Statement 10: Prepare for airway management,

increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias and inappropriate dosing and

including intubation if necessary, if there is any suggestion of

therefore should be avoided whenever In patients

airway edema (eg, hoarseness or stridor) or associated respira-

with actual or impending cardiovascular collapse unresponsive to

tory compromise. (Moderate Recommendation; C Evidence)

an epinephrine infusion or when an epinephrine infusion is notimmediately available, slow administration of a 50-mg (0.5 mL of

Asphyxia can occur in anaphylaxis because of upper airway

1:10,000) bolus of IV epinephrine might be necessary.

swelling or brTherefore, it is necessary to prepare

Summary Statement 9: If IV access is not readily available in

for airway management, including intubation when necessary, if

patients experiencing anaphylaxis, obtain IO access and

there is any suggestion of airway edema (hoarseness or stridor) or

administer epinephrine by this route. (Moderate Recommen-

associated respiratory compromise. In severe cases of anaphylaxis,

dation; D Evidence)

airway management is an essential part of the treatment plan.

Whether to intubate the patient is a difficult decision. Airway

Intraosseous fluid and medication administration is rapid, safe,

management begins with preoxygenation, an assessment of the

and effective.In animals, minimally delayed but equivalent

level of predicted difficulty of laryngoscopy, and preparation.

hemodynamic effects have been seen with IO and IV administrations.

Various algorithms and scores have been designed to help predict

Drug delivery appears to be slightly less when IO epinephrine is given

difficult laryngoscopy, but their utility in the ED setting is limit

in the tibia than when it is given in the sternum. Epinephrine can be

Although a quick assessment of the airway should occur, given the

infused by an IV or IO route at a rate of 1 mg/min and titrated to the

significant potential for pharyngeal and laryngeal edema, laryn-

necessary hemodynamic response, increasing to a maximum of 10.0

goscopy should be presumed to be difficult. Preparation includes

mg/min for adults and adolescents. A starting dose of 0.1 mg/kg per

selection and preparation of initial and back-up airway equipment

minute is recommended for childr

(including suction), optimizing patient positioning, pharmacology,

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

and the outlining of an initial and back-up airway management

Epinephrine has been known for many years to effectively

Upper airway edema can preclude rescue ventilation, so

reverse bronchospasm. Sometimes, however, bronchospasm can

the merits of an awake fiberoptic intubation should be strongly

persist despite treatment with epinephrine. Therefore, current

weighed against the benefits and risks of rapid sequence intubation.

approaches used to treat bronchospasm, such as b-adrenergic ag-

When selecting airway management medications, because pa-

onists, should be readily available if needed. There are no studies

tients with anaphylaxis requiring intubation are often hemody-

evaluating the effectiveness of b-adrenergic agonists in the treat-

namically unstable, medications should be avoided that depress

ment of bronchospasm occurring as part of anaphylaxis. However,

blood pressure. Paralytics should be used with caution, because

there is no reason to believe that the treatment of bronchospasm

mask ventilation can be impossible in the setting of upper airway

during anaphylaxis is different than the treatment of broncho-

edema. Because the airway should be presumed difficult, optimizing

spasm in patients who are not in anaphylaxis. This conclusion has

the first look is essential no matter what approach is used. Once the

been supported by observation of the effectiveness of inhaled b-

patient is intubated, post-intubation management should continue

adrenergic agonists in treating bronchospasm that occurs during

with sedation and ventilator management. For the wheezing patient

anaphylaxis. A b-agonist, such as albuterol, can be administered by

with anaphylaxis, minimize breath stacking and barotraumas by

a metered-dose inhaler (2e6 inhalations) or nebulizer (2.5e5 mg in

allowing adequate exhalation time. In those with bronchospasm,

3 mL of saline and repeated as necessary) for bronchospasm that

ketamine, a sedative with bronchodilator properties, can be used

has not responded to epinephrine.

after intubation. Peri-intubation decompensation has a broad dif-ferential diagnosis. Because of the frequency of bronchospasm in

Summary Statement 14: Consider extracorporeal membrane

anaphylaxis, barotrauma should be considered.

oxygenation in patients with anaphylaxis who are unresponsive

Nebulized epinephrine has been shown to alleviate respiratory

to traditional resuscitative efforts. (Moderate Recommendation;

distress associated with upper airway obstruction in childhood

croupThe vasoconstrictive (a1) effects likely account for the

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is becoming more readily

decrease of upper airway edema. Similarly, and based on anecdotal

available in the ED and can be applied to anyone with reversible

experience, aerosolized epinephrine also can decrease oropharyngeal

causes of pulmonary and/or cardiac failure. Patients with anaphylaxis

edema and make airway management less difficult in anaphylaxis.

who are unresponsive to traditional resuscitative efforts should be

Summary Statement 11: For patients with circulatory collapse

considered candidates for this potentially life-saving therapy. There

from anaphylaxis, aggressively administer large volumes of IV or

are several case reports of successful resuscitation of refractory

IO normal saline through large-bore catheters. (Strong Recom-

anaphylaxis involving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or

mendation; B Evidence)

operative cardiopulmonary bypass.The decision to initiateextracorporeal membrane oxygenation can be difficult but should be

Aggressive fluid resuscitation helps to counteract the significant

considered early in patients who are failing to respond to traditional

plasma leak associated with anaphylaxis and complement parenteral

resuscitative measures and before irreversible ischemic acidosis

epinephrine therapy. Children might require successive IV fluid

boluses of 20 mL/kg and adults might require successive IV boluses of1,000 mL to maintain blood pressure in the early stages of anaphylaxis.

Summary Statement 15: Do not routinely administer antihista-

To overcome venous resistance, fluids administered through IO cath-

mines or corticosteroids instead of epinephrine. There is no

eters should be infused under pressure using an infusion pump, pres-

substitute for epinephrine in the treatment of anaphylaxis.

sure bag, or manual pressure. As blood pressure stabilizes, fluid rates

Administration of H1 and/or H2 antihistamines and corticoste-

should be adjusted. Care should be taken to avoid volume overload in

roids should be considered adjunctive therapy. (Strong Recom-

certain patients, such as those with a history of left ventricular failure.

mendation; B Evidence)

Summary Statement 12: Administer glucagon (especially if the

Use of antihistamines in anaphylaxis is believed justified based

patient is receiving b-blockers) if parenteral epinephrine and

on their mechanism of action and effectiveness in other allergic

uid resuscitation fail to restore blood pressure. (Moderate

diseases, such as allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis. Many

Recommendation; B Evidence)

clinical manifestations of anaphylaxis, including vasodilatation,increased

Norepinephrine, vasopressin, and other pressors have been used

contraction, and increased airway secretions, are mediated by

with success in patients in anaphylaxis with refractory hypotension

histamine. However, there is no direct evidence to show that an-

(see Infusions of glucagon have been used to treat

tihistamines are effective in anaphyIn fact, their onset of

anaphylaxis that is refractory to epinephrine in some patients on b-

action is not rapid enough to be useful in the acute management of

blockers.There are numerous case reports of treatment refractory

anaphylaxis. Therefore, epinephrine administration should not be

anaphylaxis in patients on b-blockers.There also are case re-

delayed in patients with anaphylaxis while the patient is observed

ports of such patients responding favorably to glucagon infusion

for a response to antihistamines. Antihistamines are never a sub-

when standard therapy has failed. Glucagon increases cyclic aden-

stitute for epinephrine in the treatment of anaphylaxis. The rec-

osine monophosphate intracellularly, independent of adrenergic

ommended dose for diphenhydramine, an H

receptors, and might reverse refractory hypotension and broncho-

intramuscular or by slow IV infusion is 25 to 50 mg in adults and 1

spasm.Although data are very limited, glucagon infusion should

to 50 mg/kg 50 mg in children. Oral diphenhydramine and other

be considered when patients are not responding to traditional

oral first- or second-generation H

management. The recommended dose of glucagon is 1 to 5 mg

1 antihistamines also can be used.

2 antihistamines, such as cimetidine, at an IV dose of 4 mg/kg, are

e30 mg/kg [maximum, 1 mg] in children) administered intrave-

used widely in anaphylaxis treatment. They are recommended as

nously over 5 minutes and followed by an infusion of 5 to 15 mg/min

second-line medications in the treatment of anaphylaxis in most

titrated to clinical response. Airway protection is important because

guidelines and other well-known references.

emesis and possible aspiration is a possible side effect of glucagon.

Corticosteroids also have a slow onset of action (4e6 hours) and

Summary Statement 13: Administer an inhaled b-agonist if

therefore, like antihistamines, are not effective in the acute man-

bronchospasm is a component of anaphylaxis. (Moderate

agement of anaphylaxis. There is no strong evidence that supports

Recommendation; B Evidence)

the use of corticosteroids in the management of anaphylaxis.

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

Moreover, there no definitive evidence to indicate that corticoste-

longer periods of observation should be considered for patients

roids decrease the risk of biphasic reactions, although there is a

who have a history of risk factors for more severe anaph

theoretical possibility, owing to their anti-inflammatory properties,

Longer periods of observation should be considered in patients

that they could decrease such reactDosing of corticosteroids

who ingested the allergen, required more than 1 dose of

should be 1.0 to 2.0 mg/kg per dose of methylprednisolone or an

epinephrine, had hypotension or pharyngeal edema, or have a

equivalent formulation. Oral doses of prednisone also can be

history of asthma.

considered (1.0 mg/kg, up to 50 mg).

Patients allowed to leave the ED after complete resolution of

Summary Statement 18: Prescribe auto-injectable epinephrine

symptoms of anaphylaxis do not routinely need further treatment

for patients who have experienced an anaphylactic reaction and

with antihistamines or corticosteroids. There are no studies that

provide patients with an action plan instructing them on how

have evaluated the benefits of these medications after patients

and when to administer epinephrine. (Moderate Recommen-

leave the ED if their symptoms of anaphylaxis have resolved before

dation; C Evidence)

they leave the ED.

After leaving the ED, patients are at risk for reencountering the

Summary Statement 16: Identify triggers of anaphylaxis and

allergen that triggered the anaphylactic reaction treated in the ED.

consider obscure and less common triggers. (Moderate

As noted under summary statement 16, biphasic reactions can

Recommendation; C Evidence)

occur in up to 20% of patients who present with an anaphylacticreaction. Therefore, patients need to be prepared for possible

There are a myriad of triggers of anaphylaxis. The frequency of

recurrent anaphylaxis and should be given 2 auto-injectable

specific triggers can vary with age.In pediatric patients, the

epinephrine devices to carry with them at all times. Children

most common cause of anaphylaxis is food ingestion; in adults, the

weighing 15 to 30 kg can receive a 0.15-mg dose of epinephrine

cause of anaphylaxis is not identified approximately 25% of the

from an auto-injector. Children weighing more than 30 kg and

time.In older adults, medications are the most common cause of

adults can receive a 0.3-mg dose of epinephrine from an auto-

anaphylaxis, with antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

injector. Recognize that 0.01 mg/kg, the recommended dose,

drugs topping the list of The most common

cannot be exactly administered using the available auto-injector

cause of drug-induced anaphylaxis is b-lactam antibiotics, although

doses, so some judgment is required.

recently there has been an increasing number of reports of

Studies have shown that up to 30% of patients who develop

anaphylaxis or anaphylactoid reactions from biological mod-

anaphylaxis will have to administer more than 1 dose of epineph-

ifiers.Exercise, latex, and seminal fluid are other causes of

rine.A large percentage of patients use epinephrine injectors

anaphylaxis that need to be considered, as do non-IgEemediated

incorrectly and inadvertent injection of epinephrine into the digits

reactions such as to radiocontrast media.

has increased significantly in the past decade.Therefore, it is

Overall, foods, drugs, and stinging insect venom are the most

essential that health care providers demonstrate for patients the

common causes of anaphylaxis. However, the actual food compo-

proper use of an epinephrine auto-injector and confirm patient

nent causing anaphylaxis might not be readily apparent, resulting

proficiency. Parents of food-allergic children were 4 to 5 times more

in the exact cause of anaphylaxis being missed. In 1 study, 47% of

likely to effectively administer self-injectable epinephrine after a

patients with food allergy were not diagnosed with food allergy in

practical demonstrPatients and caregivers should be

the Less apparent triggers of anaphylaxis also should be

instructed to administer epinephrine at the first sign of a general-

considered (eg, galactose and a1,3 galactose, a carbohydrate found

ized reaction or if the patient develops any manifestations that

in mammalian meat), particularly in patients who present with

have preceded the development of anaphylaxis. The allergist-

delayed anaphylaxis. The allergist-immunologist should play an

immunologist can play an important role in this educational pro-

important role in identifying less readily apparent causes of

cess during follow-up.

anaphylaxis at follow-up.

Summary Statement 17: Strongly consider observing patients

Summary Statement 19: Instruct patients who have experienced

who have experienced anaphylaxis for at least 4 to 8 hours and

anaphylaxis when discharged from the ED to see an allergist-

observe patients with a history of risk factors for severe

immunologist in a timely fashion. (Moderate Recommenda-

anaphylaxis (eg, asthma, previous biphasic reactions, or pro-

tion; C Evidence)

tracted anaphylaxis) for a longer period. (Moderate Recom-mendation; C Evidence)

The cause of anaphylaxis is frequently unknown at the time of

discharge from the ED or at the time of admission to the hospital

Admission rates for anaphylaxis vary widely from 7% to 4

(see Preface). Therefore, follow-up with a physician with expertise

being somewhat lower in pediatric patients.The decision to

in the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis, such as an

admit should be based on symptom severity, response to treat-

allergist-immunologist, is extremely important.

ment, pattern of previous anaphylactic reactions (eg, a history of

Anaphylaxis might be the presentation of a mast cell disorder. In

protracted or biphasic reactions), medical comorbidities, patient

a study of patients with a history of anaphylaxis after an insect

reliability, and access to medical care. If the patient is not being

sting, approximately 8% were found to have an underlying mast cell

admitted to the hospital, a period of observation should be strongly

Mast cell disorders are diverse and can have multiple

considered in all patients diagnosed with anaphylaxis. Biphasic

manifestations and complications affecting essentially every organ

reactions occur in up to 20% of patients who develop anaphylaxis

system and ranging in severity from indolent cutaneous disorders

and could involve organ systems not affected in the initial reac-

to rapidly fatal leukemia.

There is no evidence that systemic corticosteroids will

Allergists-immunologists can obtain a detailed history, coordi-

prevent biphasic reactions. Moreover, as serum epinephrine levels

nate additional outpatient testing, provide additional allergen-

wane, symptoms can recurExpert consensus opinion has rec-

avoidance counseling, develop a detailed emergency action

ommended that patients be observed for 4 to 8 hours. However, the

plan for future reactions, provide the patient with medical identi-

time of observation should be individualized based on the same

fication jewelry, and reinforce the proper use of auto-injectable

criteria used to determine the need for admission. In addition,

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

R.L. Campbell et al. / Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 113 (2014) 599e608

Source: http://aaaai.acemlna.com/lt.php?s=bad97c655476f96a390a72c05a742011&i=17A37A1A507

JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCHVolume 12, Number 10, 1997Blackwell Science, Inc.© 1997 American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Long-Term Effects of Intravenous Pamidronate in Fibrous Dysplasia of Bone ROLAND D. CHAPURLAT,1 PIERRE D. DELMAS,1,2 DANIEL LIENS,1 and PIERRE J. MEUNIER1 Fibrous dysplasia of bone (FD) is a rare disorder characterized by proliferation of fibrous tissue in bone marrowleading to osteolytic lesions. It causes bone pain and fractures. To date the only treatment is orthopedic.Histological and biochemical similarities between FD and Paget's bone disease related to increased osteoclasticresorption led us to propose treatment with the bisphosphonate pamidronate. The aim of the study was to assessthe long-term effects of intravenous pamidronate in FD. In this open label phase III study, 20 patients with FD (11males and 9 females; mean age 31 years) received courses of 180 mg of intravenous pamidronate every 6 months(60 mg/day during 3 days by infusion). The mean duration of follow-up was 39 months (range 18 – 64). Severity ofbone pain, number of painful skeletal sites per patient, X-rays of all involved areas, serum alkaline phosphatase,fasting urinary hydroxyproline, and urinary type I collagen C-telopeptide were assessed every 6 months. Theseverity of bone pain and the number of painful sites appeared to be significantly reduced. All biochemical markersof bone remodeling were substantially lowered. We observed a radiographic response in nine patients with refillingof osteolytic lesions. A mineralization defect proven by bone biopsy was observed in one case. Four patientssustained bone stress lines, but no fracture occurred. We suggest that intravenous pamidronate alleviates bonepain, reduces the rate of bone turnover assessed by biochemical markers, and improves radiological lesions of FD.Few side effects were observed. (J Bone Miner Res 1997;12:1746–1752)

LA IDEOLOGÍA DE GÉNERO EN EL DERECHO PERUANO Y EN SUS POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS Rosa De Jesús SÁNCHEZ BARRAGÁN Kathya Lisseth VASSALLO CRUZ El objetivo del presente artículo es abordar y mostrar, hasta qué punto y en qué medida, lo que podemos denominar "ideología de género" no se muestra tan solo como un modelo de pensamiento más o menos